Not just AfD: What’s the BSW, Germany’s rising populist left party?

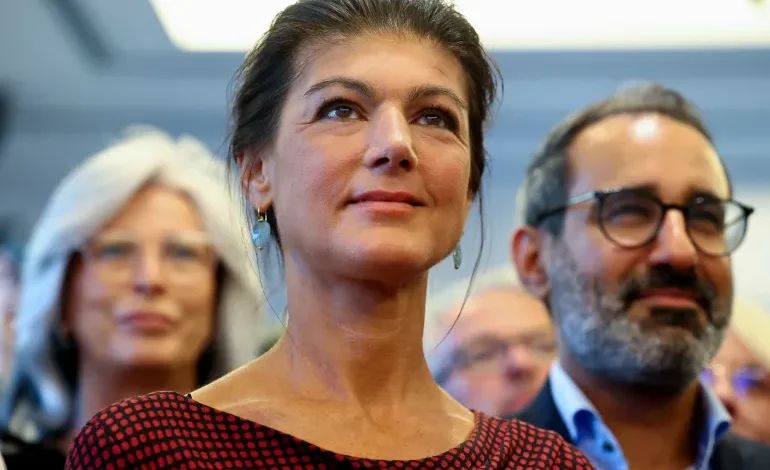

It’s the new kid on the block in German politics — and the Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW) is making waves.

A little more than nine months after its birth, the BSW, a new populist party, is rapidly emerging as a major political force in Europe’s largest economy, after stunning gains in recent state elections. The latest among them was in Brandenburg, on the outskirts of capital Berlin, where the BSW secured 13.5 percent of the vote, coming third behind the federally ruling Social Democratic Party (SPD) of Chancellor Olaf Scholz and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD).

On paper, the BSW belongs on the left – the hard left, even. But it advocates an unusual mix of left-leaning economic policies and anti-immigration rhetoric.

Experts say its success lies in cannibalising Germany’s left while also borrowing from the nationalist policies of the AfD – all while using its unorthodox brand of populism to appeal to apathetic voters.

So what is the BSW, how is it shaking up German politics, and could it be a key player in national elections scheduled for next September?

What is the BSW?

The BSW is a new left-wing alliance founded on January 8 primarily by former members of The Left party (Die Linke), a party with roots in the former communist party that ruled East Germany.

Its eponymous leader, Sahra Wagenknecht, who was born in East Germany to an Iranian father and a German mother, had previously led The Left party, which she had been a member of since its foundation in 2007.

During her time with The Left party, she positioned herself on the far left, opposing her party when it sought to form ruling coalitions for state governments with centrist, social-democratic parties. Then, in 2023, Wagenknecht had a major showdown with The Left after she organised what was described as a Ukraine peace rally in Berlin, but which critics said promoted Russian talking points. At the rally, organisers called for a ban on weapons exports to Ukraine and for pressure on Kyiv and Moscow to negotiate an end to the war.

By late 2023, a split appeared inevitable. She left the party last October.

When Wagenknecht, the former co-leader of The Left, quit the party, she was joined by nine members of parliament from the party, who also are now part of the BSW, giving the fledgling party a voice in the Bundestag even before it contested any national election.

And in a spate of state elections in recent weeks, it has demonstrated, say experts, that it has an appeal that is spreading – and that far outstrips the support that The Left party, from where the BSW emerged, today enjoys.

On September 1, the party won 11.8 percent of the vote in Saxony and 15.8 percent in Thuringia, coming third in both those elections. Brandenburg added to that pattern, with another third-place finish and double-digit vote count in the state’s September 22 election.

What has led to the success of the BSW?

The BSW’s “personality-driven, national-populist campaigns” have drawn much of its support from The Left party but also galvanised people who had not voted in previous elections, Rafael Loss, policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations told Al Jazeera.

He said it has benefitted from being the “new kid on the block” and hence can promote a programme that is “vague on policy beyond general statements about the economy, education, and climate”.

The location of the three recent state elections in eastern Germany has also benefitted the BSW.

Matt Qvortrup, professor of political science and international relations at Coventry University, told Al Jazeera that the BSW’s success in those areas represents a “nostalgia” among some voters for the communist era in East Germany between 1949 and 1990.

He said that the BSW’s promises of strong social security rooted in left-wing policies appeal to voters who had felt more protected by the welfare state before reunification.

Loss highlighted Wagenknecht’s “omnipresence” in German media as having helped raise the profile of her new party.

He noted that she has a “unique ability to deliver pointed one-liners while avoiding specifics, for example, calling for peace in Ukraine without actually explaining how she’d get Russia, the aggressor, to the negotiating table”.