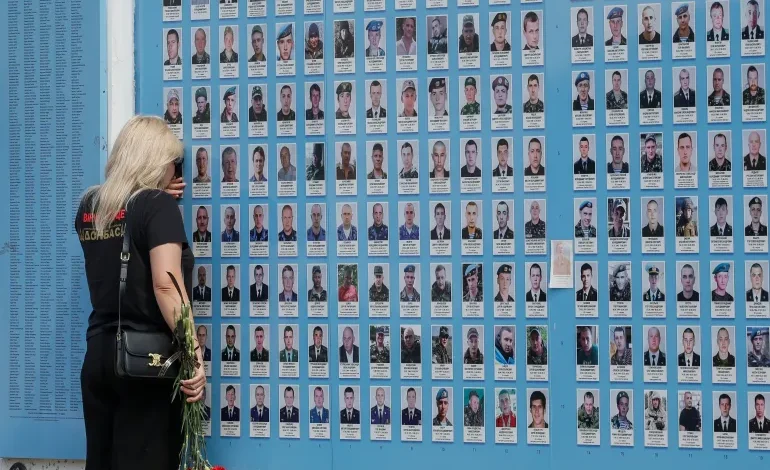

‘New ground is being broken’: EU seizes Russian profits for Ukraine

A landmark EU decision this week to send Ukraine the interest earned by hundreds of billions of dollars in Russian central bank accounts on its territory is adding urgency to a debate over what will happen to those accounts.

The difference between the two sums is enormous.

Ukraine wants to use the estimated 210 billion euros ($228bn) of Russian central bank money held in European institutions to defeat Russia on the battlefield. The EU froze those assets in February 2022, immediately after Russia invaded Ukraine. Another 50 billion euros ($54bn) are frozen around the world.

“If the world has $300bn, why not use it?” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy recently said.

After years of debate, the bloc decided on Tuesday to allow Ukraine to use just the interest earned by those accounts, which the EU believes would amount to about 2.5 to 3 billion euros ($2.7bn-$3.3bn) a year.

“This decision was the result of a lot of discussion and soul-searching,” an EU diplomatic source familiar with Ukrainian issues told Al Jazeera on condition of anonymity.

International legal experts agree it is a big step.

“There’s no precedent for the freezing of assets on this scale, and therefore the issue of what to do with the interest was never this acute,” Anton Moiseienko, a lecturer in international law at Australian National University, told Al Jazeera. “In this sense, new ground is being broken.”

It is also separate from the 12.5 billion euros ($13.6bn) a year in financial assistance they have pledged for the next four years.

A first payment is to be made in July, representing interest earned since February, when the EU ordered financial institutions to separate profits from the principal.

The institutions will keep any interest earned between February 2022 and February 2024, possibly for reconstruction purposes, European Commission sources said.

But what about the rest?

“Right now it doesn’t seem as though the EU is in any way prepared to move on to a discussion about using the principal for Ukraine,” the diplomatic source said. “There are European institutions that are against it and a lot of member states that are against it. The EU doesn’t want to risk its reputation and its prosperity.”

The European Central Bank has been especially vocal about leaving other central banks’ assets alone, worried about reputational damage to the euro. And some EU members like Hungary and Slovakia maintain strong economic ties with Russia and have made known their unease about alienating Moscow.

That leaves matters on a plateau, said Moiseienko.

“It is a placeholder, an intermediate step. But a placeholder for what?” Moiseienko said. “Transfer of those assets to Ukraine, or continue in this wait-and-see game? In terms of the overall direction of travel, it’s very unclear.”

“The EU keeps saying that Russia must pay but keeps taking steps that prevent that from happening,” he added.