Millions of donkeys killed each year to make medicine

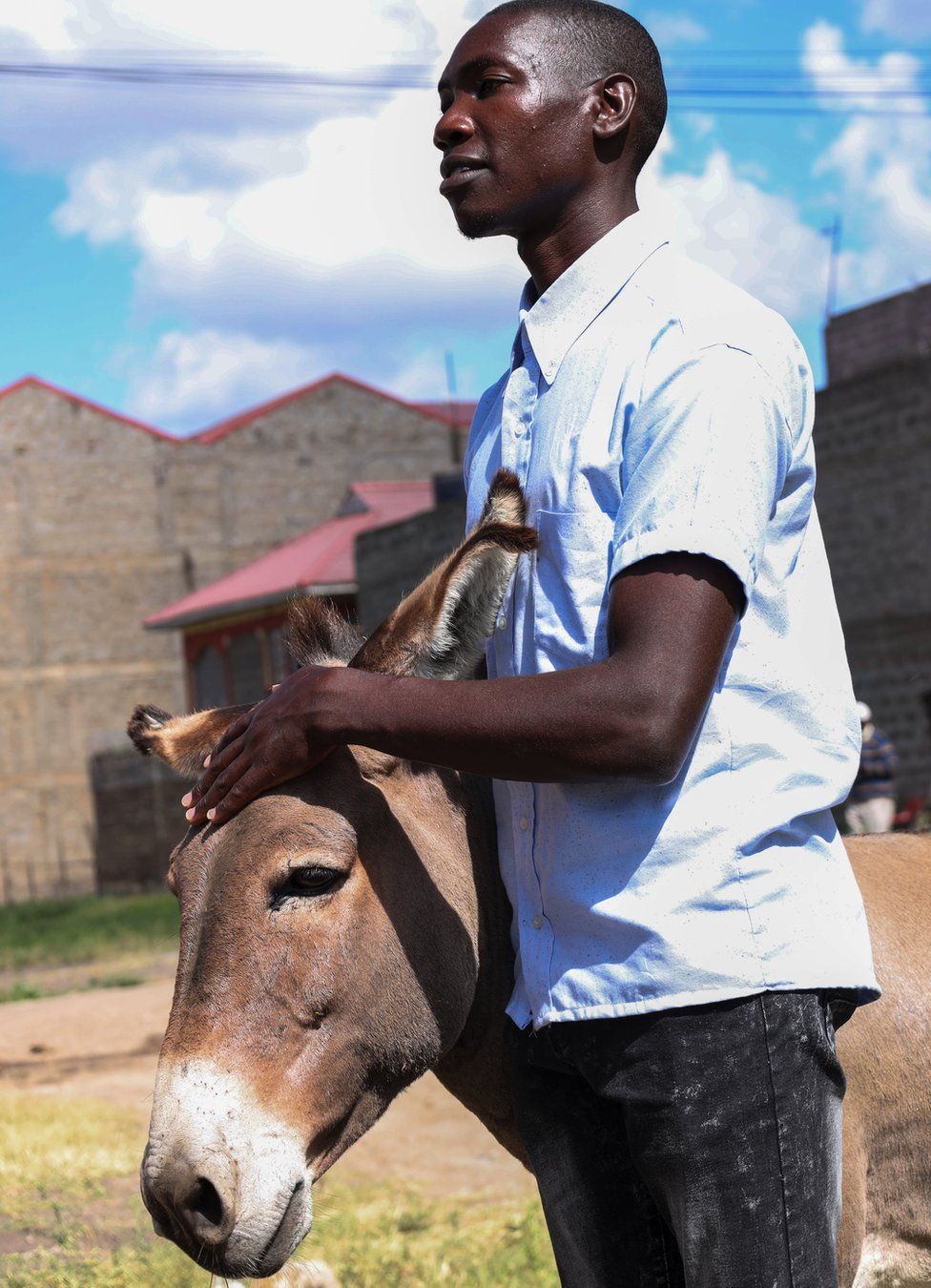

To sell water and make his living, Steve relied completely on his donkeys. They pulled him in his cart loaded with its 20 jerry cans to all his customers. When Steve’s donkeys were stolen for their skins, he could no longer work.

That day started like most others. In the morning, he left his home in the outskirts of Nairobi and went to the field to get his animals.

“I couldn’t see them,” he recalls. “I searched all day, all night and the following day.” It was three days later that he got a call from a friend telling him he had found the animals’ skeletons. “They’d been killed, slaughtered, their skin was not there.”

Donkey thefts like this have become increasingly common across many parts of Africa – and in other parts of the world that have large populations of these working animals. Steve – and his donkeys – are collateral damage in a controversial global trade in donkey skin.

Its origins are thousands of miles from that field in Kenya. In China, a traditional medicinal remedy that is made with the gelatin in donkey skin is in high demand. It is called Ejiao.

It is believed to have health-enhancing and youth-preserving properties. Donkey skins are boiled down to extract the gelatin, which is made into powder, pills or liquid, or is added to food.

Campaigners against the trade say that people like Steve – and the donkeys they depend on – are victims of an unsustainable demand for Ejiao’s traditional ingredient.

In a new report, the Donkey Sanctuary, which has campaigned against the trade since 2017, estimates that globally at least 5.9 million donkeys are slaughtered every year to supply it. And the charity says that demand is growing, although the BBC was unable to independently verify those figures.

It is very difficult to get an accurate picture of exactly how many donkeys are killed to supply the Ejiao industry.

In Africa, where about two-thirds of the world’s 53 million donkeys live, there is a patchwork of regulations. Export of donkey skins is legal in some countries and illegal in others. But high demand and high prices for skins fuel the theft of donkeys, and the Donkey Sanctuary says it has discovered animals being moved across international borders to reach locations where the trade is legal.

However, there could soon be a turning point as every African state’s government, and the government of Brazil, are poised to ban the slaughter and export of donkeys in response to their shrinking donkey populations.

Solomon Onyango, who works for the Donkey Sanctuary and is based in Nairobi, says: “Between 2016 and 2019, we estimate that about half of Kenya’s donkeys were slaughtered [to supply the skin trade].”

These are the same animals that carry people, goods, water and food – the backbone of poor, rural communities. So the scale and rapid growth of the skin trade has alarmed campaigners and experts, and has moved many people in Kenya to take part in anti-skin trade demonstrations.

The proposal for an Africa-wide, indefinite ban is on the agenda at the African Union Summit , where all state leaders meet, on 17 and 18 February.

Reflecting on a possible Africa-wide ban, Steve says he hopes it will help protect the animals, “or the next generation will have no donkeys”.

But could bans across Africa and in Brazil simply shift the trade elsewhere?

Ejiao producers used to use skins from donkeys sourced in China. But, according to the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs there, donkey numbers in the country plummeted from 11 million in 1990 to just under two million in 2021. At the same time, Ejiao went from being a niche luxury to become a popular, widely available product.

Chinese companies sought their skin supplies overseas. Donkey slaughterhouses were established in parts of Africa, South America and Asia.

In Africa, this led to a grim tug of war over the trade.

In Ethiopia, where the consumption of donkey meat is taboo, one of the country’s two donkey slaughterhouses was closed down in 2017 in response to public protests and social media outcry.

Countries including Tanzania and Ivory Coast banned the slaughter and export of donkey skins in 2022, but China’s neighbour Pakistan embraces the trade. Late last year, media reports there trumpeted the country’s first “official donkey breeding farm” to raise “some of the best breeds”.

And it is big business. According to China-Africa relations scholar Prof Lauren Johnston, from the University of Sydney, the Ejiao market in China increased in value from about $3.2bn (£2.5bn) in 2013 to about $7.8bn in 2020.

It has become a concern for public health officials, animal welfare campaigners and even international crime investigators. Research has revealed that shipments of donkey skins are used to traffic other illegal wildlife products. Many are worried that national bans on the trade will push it further underground.

For state leaders, there is the fundamental question: Are donkeys worth more to a developing economy dead or alive?

“Most of the people in my community are small-scale farmers and they use the donkeys to sell their goods,” says Steve. He was saving money from selling water to pay for school fees to study medicine.

Faith Burden, who is head vet at the Donkey Sanctuary, says that the animals are “absolutely intrinsic” to rural life in many parts of the world. These are strong, adaptable animals. “A donkey will be able to go for perhaps 24 hours without drinking and can rehydrate very quickly without any problems.”

But for all their qualities, donkeys do not breed easily or quickly. So campaigners fear that if the trade is not curtailed, donkey populations will continue to shrink, depriving more of the poorest people of a lifeline and a companion.

Mr Onyango explains: “We never bred our donkeys for mass slaughter.”

Prof Johnston says that donkeys have “carried the poor” for millennia. “They carry children, women. They carried Mary when she was pregnant with Jesus,” she says.

Women and girls, she adds, bear the brunt of the loss when an animal is taken. “Once the donkey is gone, then the women basically become the donkey again,” she explains. And there is a bitter irony in that, because Ejiao is marketed primarily to wealthier Chinese women.

It is a remedy that is thousands of years old, believed to have numerous benefits from strengthening the blood to aiding sleep and boosting fertility. But it was a 2011 Chinese TV show called Empresses in the Palace – a fictional tale of an imperial court – that raised the remedy’s profile.

“It was clever product placement,” explains Prof Johnston. “The women in the show consumed Ejiao every day to stay beautiful and healthy – for their skin and their fertility. It became this product of elite femininity. Ironically, that’s now destroying many African women’s lives.”

Steve, who is 24, is worried that, when he lost his donkeys, he lost control over his life and livelihood. “I’m just stranded now,” he says.

Working with a local animal welfare charity in Nairobi, the charity Brooke is working to find donkeys for young people – like Steve – who need them to access work and education.

Janneke Merkx, from the Donkey Sanctuary, says the more countries that put legislation in place to protect their donkeys, “the more difficult it will get”.

“What we’d like to see is for Ejiao companies to stop importing donkey skins altogether and invest in sustainable alternatives – like cellular agriculture (producing collagen in labs). There are already safe and effective ways to do that.”

Faith Burden, the Donkey Sanctuary’s deputy chief executive, calls the donkey skin trade “unsustainable and inhumane”.

“They’re being stolen, potentially walked hundreds of miles, held in a crowded pen and then slaughtered in full view of other donkeys,” she says. “They need us to speak up against this.”

Brooke has now given Steve a new donkey, a female that he has named Joy Lucky, because he feels lucky and joyful to have her.

“I know that she will help me achieve my dreams,” he says. “And I’ll make sure that she is protected.”