James Webb: Telescope reveals new detail in famous supernova

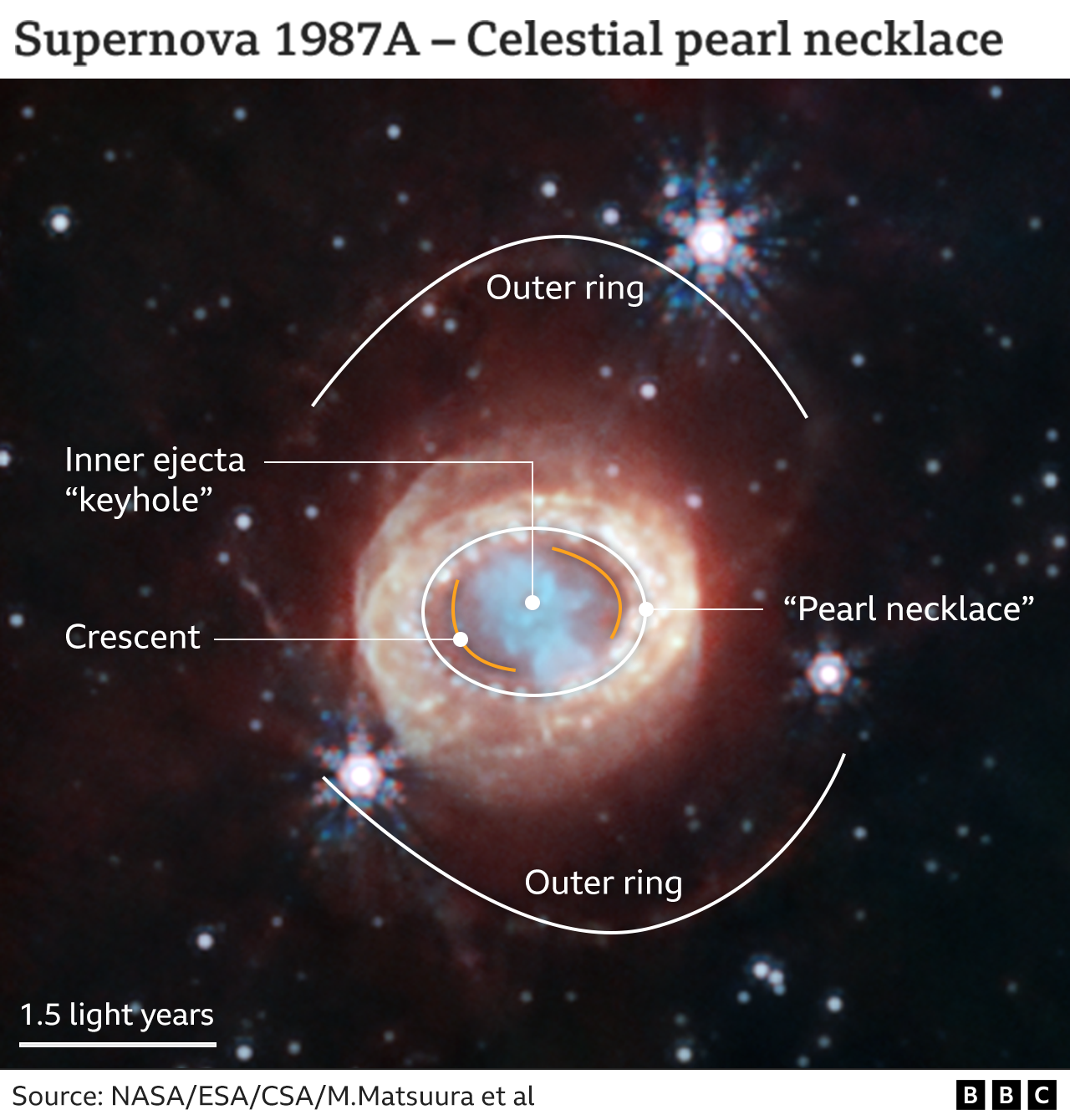

It’s like a celestial pearl necklace.

This is an image of a supernova – an exploded star – taken by the new super space telescope James Webb (JWST).

SN1987A, as it’s known, is one of the most famous and studied objects in the southern hemisphere sky.

When the star went boom in 1987, it was the nearest, brightest supernova to be seen from Earth in almost 400 years. And now the $10bn (£8bn) Webb observatory is showing us details never revealed before.

SN1987A is sited a mere 170,000 light-years from us in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy adjacent to our own Milky Way Galaxy.

Astronomers are fascinated with the object because it provides an intricate view of what happens when big stars end their days.

The series of bright rings represent bands of gas and dust thrown out by the star in its various dying phases and which have since been excited and illuminated by the expanding shockwaves emitted in the last-moment collapse and detonation.

One of these rings is that string of pearls, which comprises material ejected, scientists calculate, about 20,000 years before the final event.

Webb gives us the clearest view yet of the necklace and the diffuse light around it. Webb also spies one or two pearly additions not present in earlier images from the likes of the Hubble Space Telescope (see bottom image).

“We’re able to see new hotspots emerging outside the ring that has previously been illuminated,” explained Dr Roger Wesson from Cardiff University, UK.

“In addition, we see emission from molecular hydrogen in the ring that was not necessarily expected and something only JWST could have revealed with its superior sensitivity and resolution,” he told BBC News.

Another new feature are the crescents or arcs of emission inside the necklace but just outside the dense inner area that looks a little like a keyhole.

“We don’t really understand the crescents yet,” said Dr Mikako Matsuura, who led the latest analysis.

“This material could be being illuminated by some kind of reverse shock – a shock coming back towards the keyhole.”

What Webb can’t see is the star remnant. It’s buried somewhere in the dense dust field that is the keyhole.

The remnant should be an extremely compact object composed entirely of neutron particles and measuring just a few tens of kilometres across.

For the past 36 years every large telescope that can see SN1987A has studied its evolving shape and features.

Central to these investigations is the question of why the supernova occurred in the first place.

Astronomers think the progenitor was a hot, relatively young star, perhaps 20 to 30 times as massive as our Sun. It was certainly big enough to produce the explosion but not at its stage in life.

“One of the mysteries of this star is that it exploded when it was a blue supergiant when at the time all the theories said only red supergiant stars could explode. So unravelling that mystery has been one of the great quests,” said Dr Wesson.

“The indications are that Webb will be operational much longer than originally envisaged – maybe 20 years – and that will give us a very powerful tool to keep on monitoring SN1987A to see how it is changing.”

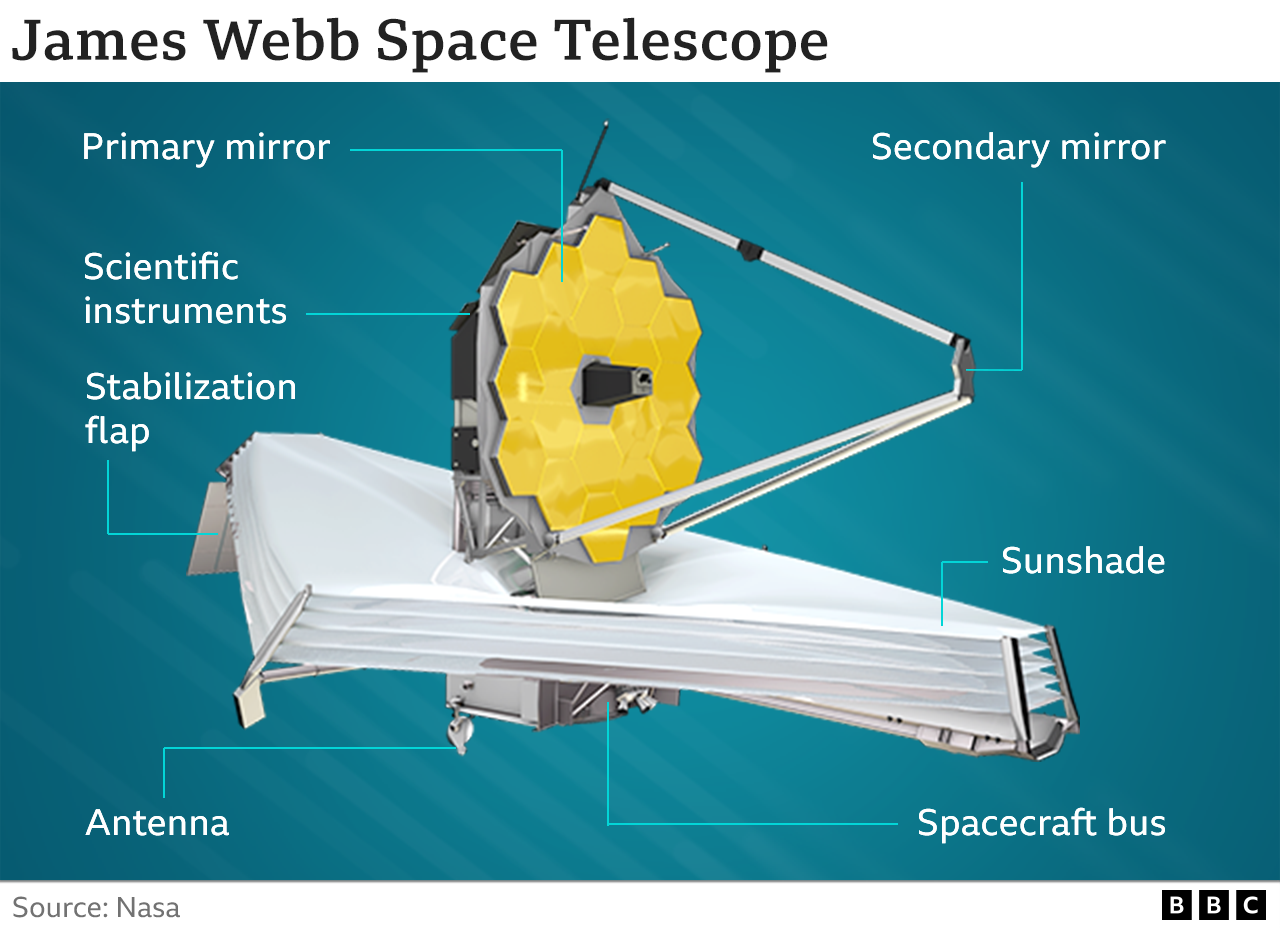

The image at the top of this page comes from Webb’s main camera, its Near-Infrared Camera or NIRCam. Combined with the telescope’s 6.5m-wide primary mirror and associated optics it takes astonishing pictures.

But Webb’s secret weapon is its suite of spectrometers, the instruments that split up the light coming from objects into their component colours. This reveals the chemistry, temperature, density and velocity of the targets under study.

Observations of SN1987A using Webb’s Near Infrared Spectrometer, or NIRSpec, will appear in a published report shortly. This is expected to contain further, exciting revelations about this remarkable supernova.