James Webb telescope detects dust storm on distant world

A raging dust storm has been observed on a planet outside our Solar System for the first time.

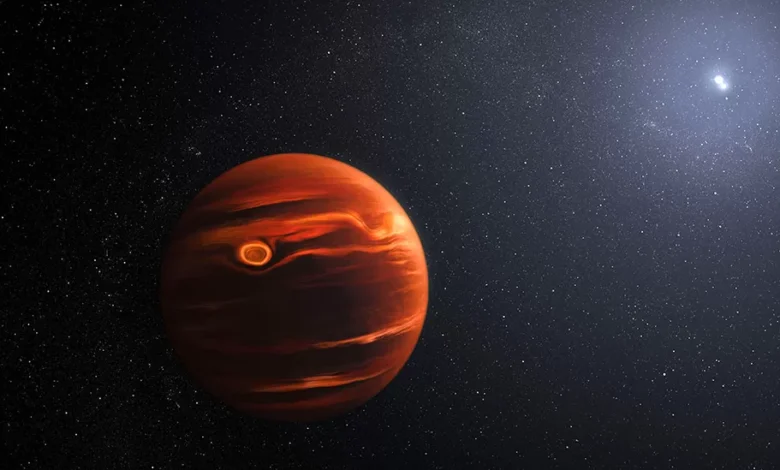

It was detected on the exoplanet known as VHS 1256b, which is about 40 light-years from Earth.

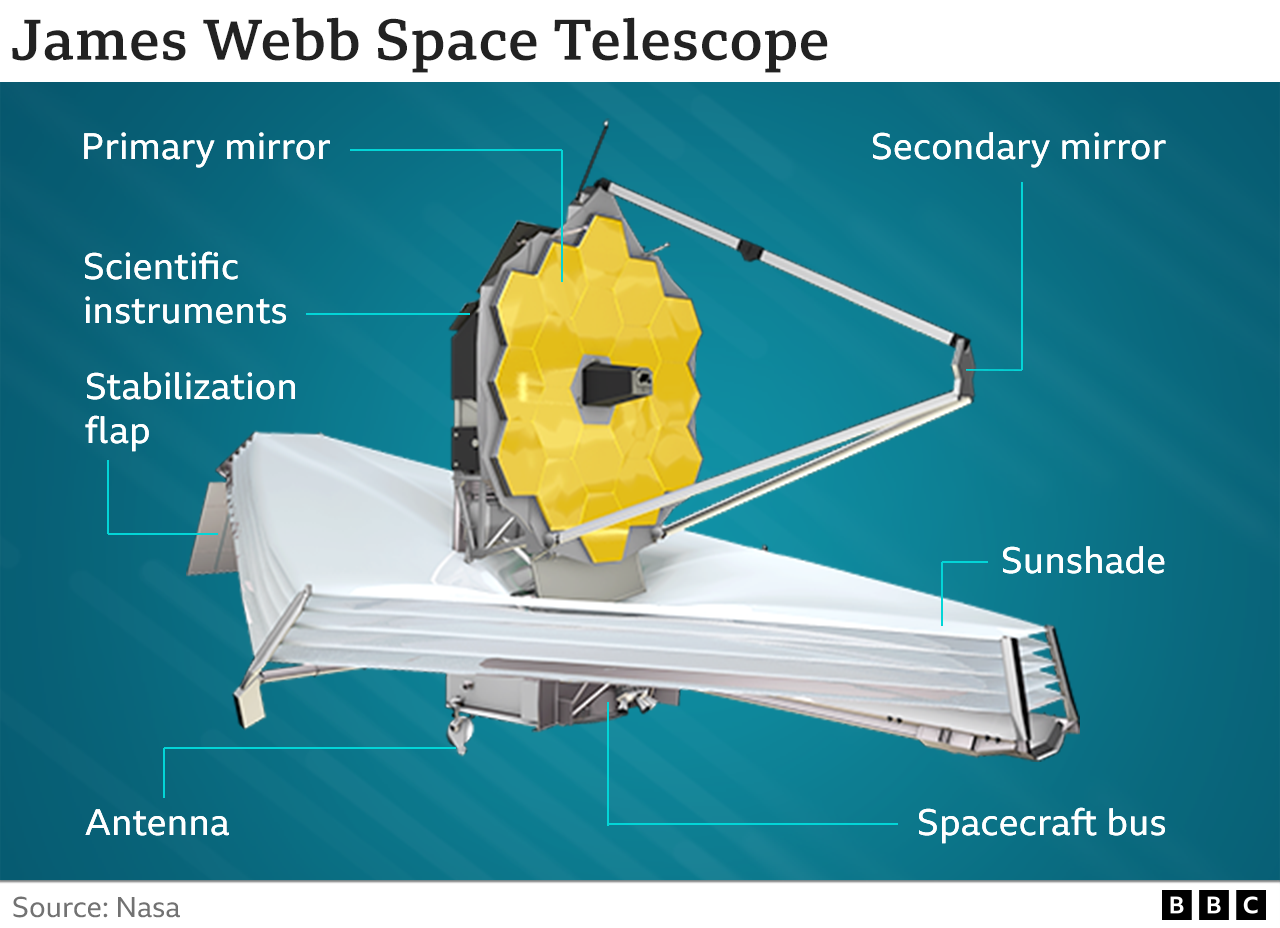

It took the remarkable capabilities of the new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to make the discovery.

The dust particles are silicates – small grains comprising silicon and oxygen, which form the basis of most rocky minerals.

But the storm detected by Webb isn’t quite the same phenomenon you would get in an arid, desert region on our planet. It’s more of a rocky mist.

“It’s kind of like if you took sand grains, but much finer. We’re talking silicate grains the size of smoke particles,” explained Prof Beth Biller from the University of Edinburgh and the Royal Observatory Edinburgh, UK.

“That’s what the clouds on VHS 1256b would be like, but a lot hotter. This planet is a hot, young object. The cloud-top temperature is maybe similar to the temperature of a candle flame,” she said.

VHS 1256b was first identified by the UK-developed Vista telescope in Chile in 2015.

It’s what’s termed a “super Jupiter” – a planet similar to the gas giant in our own Solar System, but a lot bigger, perhaps 12 to 18 times the mass.

It circles a couple of stars at great distance – about four times the distance that Pluto is from our Sun.

Earlier observations of VHS 1256b showed it to be red-looking, hinting that it might have dust in its atmosphere. The Webb study confirms it.

“It’s fascinating because it illustrates how different clouds on another planet can be from the water vapour clouds we are familiar with on the Earth,” said Prof Biller.

“We see carbon monoxide (CO) and methane in the atmosphere, which is indicative of it being hot and turbulent, with material being drawn up from deep.

“There are probably multiple layers of silicate grains. The ones that we’re seeing are some of the very, very fine grains that are higher up in the atmosphere, but there may be bigger grains deeper down in the atmosphere.”

Telescopes have previously detected silicates in so-called brown dwarfs. These are essentially star-like objects that have failed to ignite properly. But this is a first for a planet-sized object.

To make the detection, Webb used its Mid-Infrared Instrument (Miri), part-built in the UK, and its Near-Infrared Spectrometer (NirSpec).

They didn’t take pretty pictures of the planet, at least not in this instance. What they did was tease apart the light coming from VHS 1256b into its component colours as a way to discern the composition of the atmosphere.

“JWST is the only telescope that can measure all these molecular and dust features together,” said Miri co-principal investigator Prof Gillian Wright, who directs the STFC UK Astronomy Technology Centre, also in Edinburgh.

“The dynamic picture of the atmosphere of VHS 1256b provided by this study is a prime example of the discoveries enabled by using the advanced capabilities of Miri and NirSpec together.”

JWST’s primary mission is to observe the pioneer stars and galaxies that first shone just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. But a key objective is to investigate exoplanets. In Miri and NirSpec it has the tools to study their atmospheres in unprecedented detail.

Scientists hope they might even be able to tell whether some exoplanets have conditions suitable to host life.

Astronomers are reporting Webb’s observations of VHS 1256b in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

James Webb is a collaborative project of the US, European and Canadian space agencies. It was launched in December 2021 and is regarded as the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.