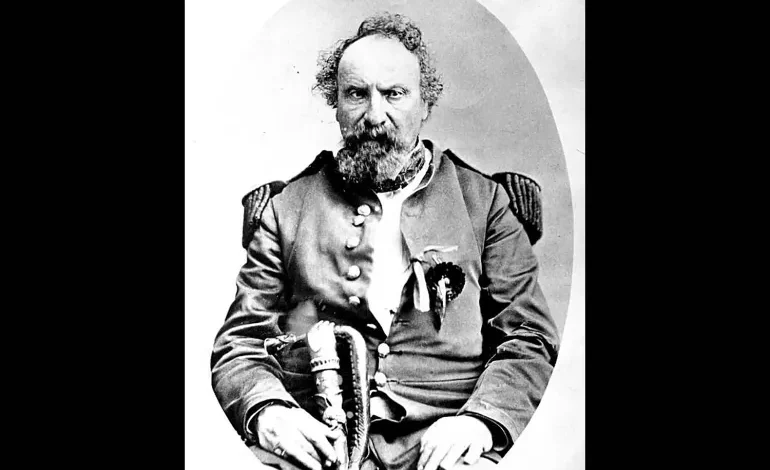

In 1859, a South African declared himself emperor of the United States

On the morning of September 17, 1859, a “well-dressed and serious-looking man” walked into the offices of The San Francisco Evening Bulletin and – without explanation – handed over a document that he wished to see published. Intrigued, the paper’s editors carried a proclamation in that evening’s edition on page 3:

“At the peremptory request and desire of a large majority of the citizens of these United States, I, Joshua Norton, formerly of Algoa Bay, Cape of Good Hope, and now for the last 9 years and 10 months past of San Francisco, California, declare and proclaim myself Emperor of these United States.”The document then asked representatives from around the country to meet in San Francisco’s Musical Hall “to make such alterations in the existing laws of the Union as may ameliorate the evils under which the country is laboring”. It was signed, “NORTON I, Emperor of the United States”.

Norton was referring to the heightened political tension surrounding slavery. The Southern states largely depended on enslaved people for their economy, but the North opposed it. When the anti-slavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, Southern states began pulling out of the union – ultimately resulting in the Civil War.

The musical hall burned down just nine days before the meeting was due to take place, and although Norton rescheduled it at a different venue, apparently no one showed up.

As Tesla billionaire Elon Musk continues to influence the trajectory of the United States, it seems a good time to remember another South African who also tried to shape the national conversation, albeit not as successfully.Musk, Trump’s appointed leader of the US government’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), has cancelled $1bn worth of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion contracts, drastically reduced USAID’s funding of charitable programmes around the world, and tried to reduce the federal government workforce by two million people.

He has divided opinion, with some expressing their ire by setting Tesla cars and showrooms alight, while others appreciate him bringing his children into the Oval Office and brandishing a chainsaw on stage during Trump’s presidential campaign.

Norton didn’t have this kind of access to power, and he didn’t inspire a public backlash. But he was a cult figure, says John Lumea, founder of the Emperor Norton Trust, a nonprofit which works to promote Norton’s legacy through research and advocacy, and the leading contemporary scholar of Norton’s life. What’s more, “he was way ahead of his time on human rights issues”.

As Jane Ganahl, co-founder of the San Francisco literary festival Litquake, wrote in a 2018 endorsement of a proposal to rename part of the Bay Bridge in his honour: “Emperor Norton could have been a time traveller. A 19th-century man with 21st-century sensibilities, Joshua Norton fought for the rights of immigrants, women and those who suffered under religious persecution.”