How is climate change affecting hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones?

The 2024 Atlantic hurricane season has come to an end, and it brought a number of particularly damaging storms.

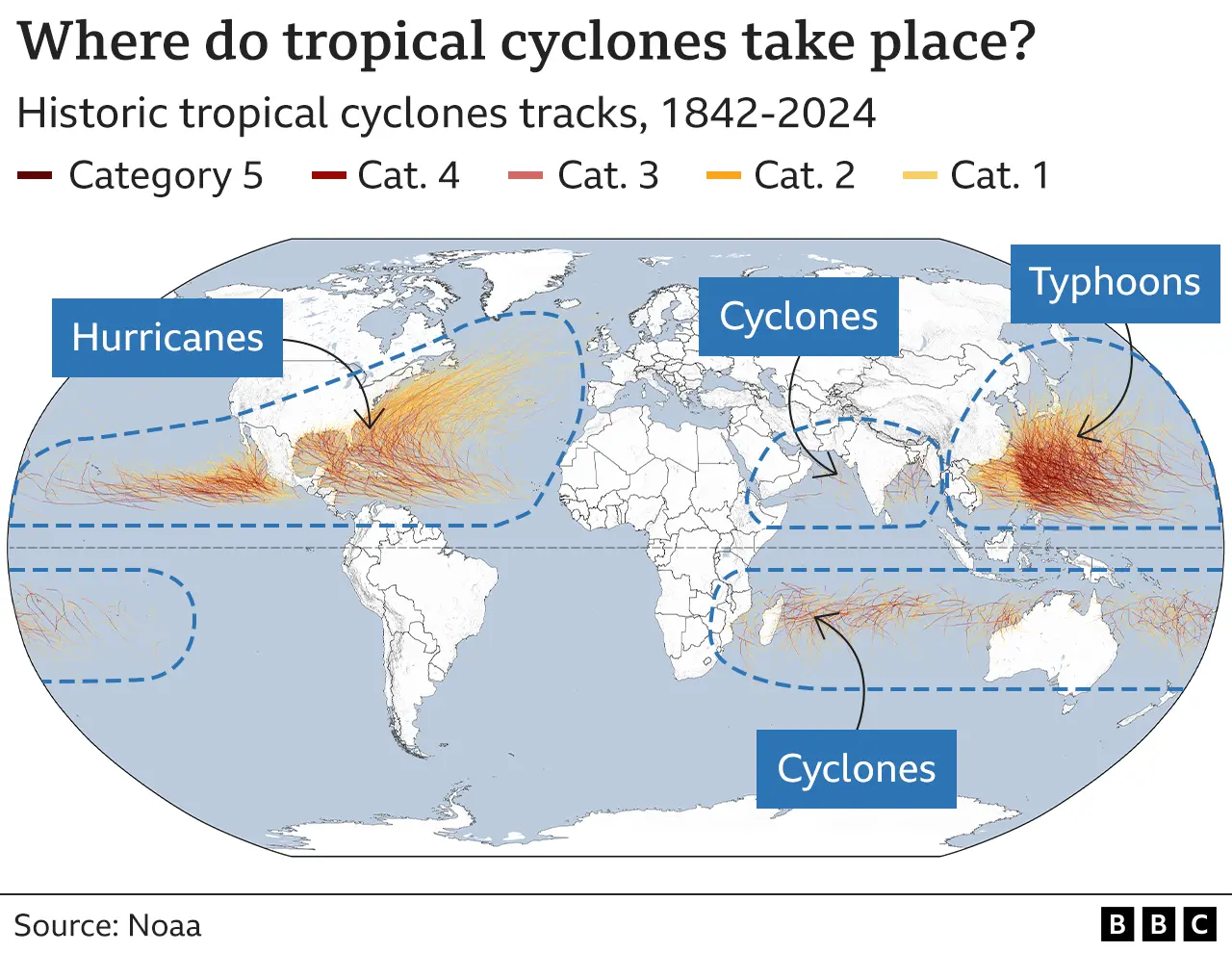

Climate change is not thought to increase the number of hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones worldwide.

But warmer oceans and a warmer atmosphere can make those that do form even more intense, with potentially higher wind speeds, heavier rainfall, and a greater risk of coastal flooding.

What are hurricanes?

Hurricanes are powerful storms which develop in warm tropical ocean waters.

In other parts of the world, they are known as cyclones or typhoons. Collectively, these storms are referred to as “tropical cyclones”.

Tropical cyclones are characterised by very high wind speeds, heavy rainfall, and storm surges – short-term rises to sea-levels. This often causes widespread damage and flooding.

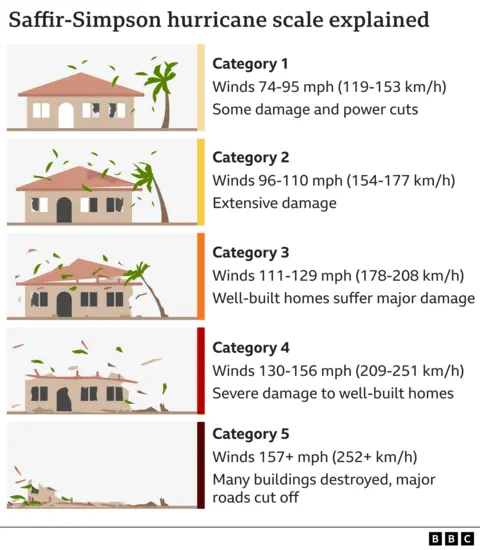

Hurricanes can be categorised by their peak sustained wind speed.

Major hurricanes are rated category three and above, meaning they reach at least 111mph (178km/h).

How do hurricanes form?

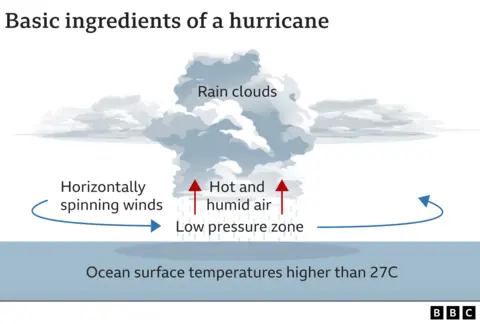

Hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones begin as atmospheric disturbances – such as, for example, a tropical wave, an area of low pressure where thunderstorms and clouds develop.

As warm, moist air rises from the ocean surface, winds begin to spin. The process is linked to how the Earth’s rotation affects winds in tropical regions just away from the equator.

For a hurricane to develop and keep spinning, the sea surface generally needs to be at least 27C to provide enough energy, and the winds need to not vary much with height.

If all these factors come together, an intense hurricane can form, although the exact causes of individual storms are complex.

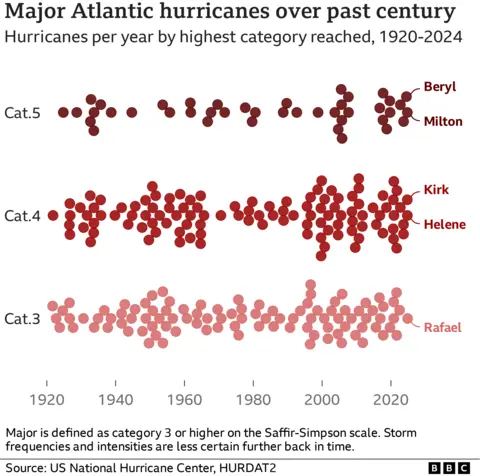

Have hurricanes been getting worse?

Globally, the frequency of tropical cyclones has not increased over the past century, and in fact the number may have fallen – although long-term data is limited in some regions.

But it is “likely” that a higher proportion of tropical cyclones across the globe are reaching category three or above, meaning they reach the highest wind speeds, according to the UN’s climate body, the IPCC.

The IPCC quotes “medium confidence” that there has been an increase in the average and peak rainfall rates associated with tropical cyclones.

The frequency and magnitude of “rapid intensification events” in the Atlantic has also likely increased. This is where maximum wind speeds increase very quickly, which can be especially dangerous.

There also seems to have been a slowdown in the speed at which tropical cyclones move across the Earth’s surface. This typically brings more rainfall for a given location. For example, in 2017 Hurricane Harvey “stalled” over Houston, releasing 100cm of rain in three days.

In some places, the average location where tropical cyclones reach their peak intensity has shifted poleward – for example the western North Pacific. This can expose new communities to these hazards.

And there is some evidence the increased intensity of US hurricanes means they are causing more damage.

Is climate change affecting hurricanes?

Assessing the precise influence of climate change on individual tropical cyclones can be challenging due to the complexity of these storm systems.

But rising temperatures do affect these storms in several measurable ways.

Firstly, warmer ocean waters mean storms can pick up more energy, leading to higher wind speeds.

Maximum wind speeds of hurricanes between 2019 and 2023 were boosted by an estimated 19mph (30km/h) on average as a result of human-driven ocean warming, according to a recent study.

Secondly, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, leading to more intense rainfall.

Climate change made the extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey in 2017 around three times more likely, according to one estimate.

Finally, sea-levels are rising, mainly due to a combination of melting glaciers and ice sheets, and the fact that warmer water takes up more space. Local factors can also play a part. This means storm surges happen on top of already elevated sea levels, worsening coastal flooding.

For example, it is estimated that flood heights from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 – one of America’s deadliest storms – were 15-60% higher than they would have been in the climate conditions of 1900.

Overall, the IPCC concludes that there is “high confidence” that humans have contributed to increases in precipitation associated with tropical cyclones, and “medium confidence” that humans have contributed to the higher probability of a tropical cyclone being more intense.

How might hurricanes change in the future?

The number of tropical cyclones globally is unlikely to increase, according to the IPCC.

But as the world warms, it says it is “very likely” they will have higher rates of rainfall and reach higher top wind speeds. This means a higher proportion would reach the most intense categories, four and five.

The more global temperatures rise, the more extreme these changes will tend to be.

The proportion of tropical cyclones reaching category four and five may increase by around 10% if global temperature rises are limited to 1.5C, increasing to 13% at 2C and 20% at 4C, the IPCC says – although the exact numbers are uncertain.