How electric scooters are driving China’s salt battery push

The country is racing ahead of the rest of the world in bringing sodium-ion batteries to the mass market. This time, through scooters.

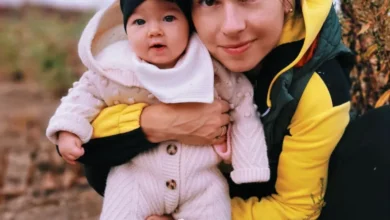

Dozens of glitzy electric mopeds are lined up outside a shopping mall in the city of Hangzhou in eastern China, drawing passersby to test them.

But these Vespa-like scooters, which sell for between £300 and £500 ($400 and $660), are not powered by the mainstream lead-acid or lithium-ion cells, commonly used in electric two-wheelers. Instead, their batteries are made from sodium, an abundant element that can be extracted from sea salt.

Next to the scooters stand a few fast-charging pillars, which can replenish the vehicles’ power level from 0% to 80% in 15 minutes, according to Yadea, the major Chinese two-wheeler manufacturer holding this promotional event in January 2025 for its newly launched mopeds and charging system. There is also a battery-swapping station, which enables commuters to drop in their spent cells in exchange for fresh ones with a scan of a QR code.

Yadea is one of many companies in China trying to build a competitive edge in alternative battery technologies, a trend that shows just how fast the country’s clean-technology industry is developing.

Even as the rest of the world tries to close its gap with China in the race to make cheap, safe and efficient lithium-ion batteries, Chinese companies have already taken a head-start towards mass producing sodium-ion batteries, an alternative that could help the industry reduce its dependence on key raw minerals.

Chinese carmakers were the first in the world to launch sodium-powered cars. But the impact of these models – all of them tiny with short ranges – has been low so far.

In April 2025, the world’s largest battery manufacturer, China’s CATL, announced its plan to mass-produce sodium-ion batteries for heavy-duty trucks and cars this year under a new brand Naxtra.

China’s grid operators have also started to build energy storage stations using sodium-ion batteries to help the grid absorb renewables.

Chinese companies’ multi-pronged strategy in driving sodium-ion batteries will put it in a leading position of a global race – should there be one, says Cory Combs, who researches critical minerals and supply chains at Beijing-based consultancy Trivium China. He says it remains to be seen whether sodium-ion batteries will really take off.

But one segment that is betting big on sodium-ion batteries is the two-wheeler, a fast-growing and highly competitive market in China.

Yadea has brought three sodium-powered models to the market so far and is planning to launch more. It has also established the Hangzhou Huayu New Energy Research Institute to research emerging battery chemistries, particularly sodium-ion.

“We want to bring technology from the lab to customers fast,” Zhou Chao, the company’s senior vice president, said in January during a talk show on China Central Television in January.

Cue the ‘little electric donkey’

Two-wheelers are an extremely popular mode of transport in many Asian countries, including Vietnam and Indonesia. In China, they are ubiquitous, carrying their owners to shops, offices, metro stations and everywhere in between. Because they are practical and versatile, the Chinese have given them an endearing nickname: “little electric donkeys”.

“Two-wheeled vehicles typically operate over shorter distances and at lower speeds [than cars], making them less demanding in terms of energy density and power output,” says Chen Xi, who researches energy storage materials and devices at Xi’an-Jiaotong Liverpool University in China. A sodium-ion battery carries significantly less energy than a lithium-ion battery of the same size, which means it has a lower energy density.

For two-wheelers, sodium-ion batteries’ main rivals are lead-acid ones, whose energy density and rechargeable cycles are even lower. Their only advantage is that they are cheaper than both sodium and lithium-ion batteries currently, Xi says.

The sheer number of two-wheelers in Asia paves a promising pathway to achieving economies of scale. In China alone, around 55 million electric two-wheelers were sold in 2023 – nearly six times the number of all pure, hybrid and fuel-cell electric cars combined sold in the country that year – according to Shanghai-based consultancy iResearch.

Scale production was the goal of Yadea. Zhou said at the talk show that the firm was seeking to bring sodium batteries to tens of millions of ordinary commuters by not only fitting them into two-wheelers, but also building a charging ecosystem to enable people to use these models without stress.

To test the waters, in 2024 Yadea began a pilot programme with 150,000 food delivery couriers working in Shenzhen, a mega city of 17.8 million people in southern China, reported Shenzhen News. The goal was to enable them to hand in a spent Yadea sodium-ion batteries at its partners’ battery-swapping stations in exchange for a fully charged one within 30 seconds, Yadea said.

Yadea and other companies, such as battery-swapping firm Dudu Huandian, have grown so rapidly in Shenzhen the city now aims to become a “battery-swapping city”. It aims to install 20,000 charging or swapping pods for various types of batteries for electric scooters in 2025, and 50,000 by 2027, according to Shenzhen Electric Bicycle Industry Association, a trade body that is working with the Shenzhen government to promote battery swapping. The city – which already has a “battery-swapping park” – will build a vast network of battery swapping facilities to enable residents to find a station every five minutes, the trade body says.

Boom and bust

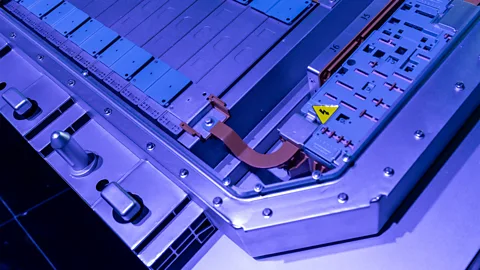

Sodium-ion and lithium-ion batteries have similar structures. The main difference is the ions they use – the particles shuttling back and forth between a battery’s positive and negative sides to store and release energy.

Sodium is widely dispersed in the sea and the Earth’s crust, making it about 400 times more abundant than lithium. Sodium-ion cells are therefore more accessible and potentially cheaper to produce at scale. They could also free the battery industry from choking points in current supply chains.

Lithium ore is currently predominantly mined in Australia, China and Chile, but the processing of the mineral is concentrated in China, which has nearly 60% of the world’s lithium-refining capacity.

Sodium-ion batteries are not a recent invention. Their fate has been intertwined with that of lithium-ion batteries. The research and development of both cells began about half a century ago, with Japan leading the global effort. But after Japanese electronics company Sony launched the world’s first lithium-ion battery in 1991, its huge commercial success led the development of sodium-ion technology to be largely paused – until the beginning of this decade. By then, China had become the dominant battery force worldwide through years of an industrial push by the government.

2021 proved to be a turning point for sodium-ion batteries. The global prices for battery-grade lithium skyrocketed, multiplying over fourfold in a year due to strong demand for electric vehicles (EV) and the Covid-19 pandemic. Battery and EV manufacturers began to look for alternatives.

CATL launched its first-ever sodium-ion battery in July that year, and the move “triggered high industry interest”, says Phate Zhang, founder of the Shanghai-based EV news outlet CnEVPost. Lithium’s prices continued to soar in 2022, driving more cost-conscious Chinese companies towards sodium, he notes.

“The relative abundance of sodium and China’s interest in a resilient battery supply chain has been a central factor in driving research and development efforts,” says Kate Logan, a director at the Asia Society Policy Institute in Washington DC who focuses on China’s climate and clean energy policies. Around the time of the mineral’s price hike, the country imported roughly 80% of the lithium ore it refined, mainly from Australia and Brazil.

But the price of lithium started to plunge in late 2022 and is at a fraction of its peak level today. One reason is that major Chinese battery makers such as CATL and Gotion have expanded their lithium-processing capacity, Zhang says. China has also boosted efforts to find and develop domestic lithium reserves.

As a result, the “frenzy” around sodium-ion in the last couple of years has “relaxed”, Combs notes. “Lithium is pretty squarely back in the leadership role again within China.”

Seeking safety

For many, though, there are other good reasons to take up sodium-ion batteries. One is safety.

In 2024, China was shocked by a wave of battery fires, mostly triggered by the self-combustion of lithium-ion batteries in two-wheelers. Globally, fire risks at energy storage stations have become a concern. In a recent example, a blaze broke out at one such facility inside a major battery plant in California in January 2025.

Some industry insiders believe that sodium-ion batteries are safer. They are less prone to overheating and burning compared to lithium-ion ones because sodium’s chemical traits are more stable, according to some studies. But others warn that it is still too early to be certain about their safety due to a lack of relevant research.

Cold weather also makes a difference. The energy a lithium-ion battery can store and the times it can be recharged drop at sub-zero temperatures. Sodium-ion batteries are less affected by harsh conditions.

“Compared to lithium ions, sodium ions move more easily through the liquid inside the battery. This gives them better conductivity and means they need less energy to break free from the surrounding liquid,” says Tang Wei, a professor of chemical engineering at China’s Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Tang and his team have developed a new type of battery liquid they say can enable sodium-ion batteries to achieve more than 80% of their room-temperature capacity at −40C (-40F). They are working with Chinese battery firms to apply the technology onto vehicles and energy storage stations in the country’s cold regions.

Sodium-ion batteries are also expected to reduce the environmental impact of manufacturing the metals used in lithium-ion cells, particularly cobalt and nickel – heavy metals that can negatively impact humans and nature.

A 2024 study concluded that sodium-ion batteries can help the world avoid excessive mining and possible depletion of critical raw materials, but that the production process generates similar volumes of greenhouse gas emissions to lithium-ion cells.

As these batteries are still being developed, “their production processes, lifespans and energy density can all be improved”, says Zhang Shan, the study’s lead author and a researcher at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg. “Their impact on the climate may be lower than that of lithium-ion batteries in the future.”

Fuelling four-wheelers

Two of the earliest electric cars powered by sodium batteries rolled off the assembly lines in December 2023. So far, all available models have been “microcars”, officially classified as A00 in China.

But their sales only made up a tiny number of the tens of millions of EVs sold in 2024 in China, says Xing Lei, an independent analyst of the Chinese auto industry (one report found just 204 were sold in 2024).

A big downside of sodium-ion batteries is their low energy density: a 2020 study found it is at least 30% lower than their lithium counterparts. This means cars using them typically cannot travel very far on a single charge, Zhang says. “And range is a big deciding factor for people when they buy an EV.”

Sodium-ion batteries have yet to achieve mass production and currently “cannot compete with lithium-ion batteries on price or performance” in four-wheelers, making large-scale use in the next two or three years difficult, says Chen Shan, a Shanghai-based analyst on battery markets at Norwegian consultancy Rystad Energy.

The uptake of sodium scooters across China has been gradual but encouraging. A spokesperson from Yadea – which sold more than 13 million electric bikes and mopeds globally in 2024 –said that the sales of its sodium two-wheelers reached nearly 1,000 in the first three months of 2025. The company intends to build around 1,000 fast-charging pillars specifically designed for sodium-ion batteries this year in Hangzhou enabling commuters to find a station every 2km (1.2 miles), Zhou said at the talk show.

Yadea is not alone in its sodium push. Another Chinese scooter manufacturer, Tailg, has been selling sodium-powered models since 2023. FinDreams, the battery arm of EV major BYD, is building a plant in east China’s Xuzhou to make sodium batteries in partnership with Huaihai Group, a manufacturer of two and three-wheelers, according to local media.

Although lead-acid batteries will continue to dominate this industry, the market share of sodium-ion batteries has been projected to grow rapidly over the next five years. By 2030, 15% of China’s electric scooters will be powered by them, compared to 0.04% in 2023, according to an analysis by the Shenzhen-based Starting Point Research Institute, which assesses China’s battery industry.

Greening the grid

In fact, a bigger market for sodium-ion batteries may be energy storage stations, which absorb power produced at one time so it can be used later.

When they are installed in fixed locations, the disadvantages of using sodium-ion batteries in vehicles disappear. “You can just make a slightly bigger energy storage plant. It’s not moving anywhere. The weight [of the batteries] doesn’t matter,” Combs says.

Energy storage is expected to be an enormous and a rapidly growing market as countries across the globe aim to reach their climate goals. The world’s grid-scale energy storage capacity will need to grow nearly 35-fold between 2022 and 2030 if it is to achieve net-zero by 2050, according to International Energy Agency (IEA).

“This is going to be a really important market in the future, especially as renewables become more present on the grid. You’ll have more need for storage systems to balance out the variability in electricity generation, ” says Ilaria Mazzocco, a senior fellow with the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington DC-based non-profit.

Using sodium-ion batteries in energy storage stations also means that these facilities are not competing with auto companies for batteries, she notes.

China, which has seen breakneck growth of wind and solar power plants, leads the world in using energy storage to support renewables. In May 2024, it switched on its first energy storage station powered by sodium-ion batteries. Situated in southern China’s Guangxi, the plant can hold 10 megawatt-hours of power in one go, equivalent to the daily electricity needs of 1,500 households, according to Chinese state media. It is the first phase of a sodium-ion energy storage station 10 times its size.

The Guangxi project was quickly followed by another sodium-ion energy storage site in central China’s Hubei province. In fact, roughly one-fifth of the capacity of all energy storage projects planned by China’s state-run companies last year used sodium technology, according to Chinese outlet Beijixing, which tracks the power industry.

But for sodium-ion batteries to succeed in mass production the main question is whether companies can make them cheaper than lithium-ion cells, according to Zheng Jiayue, a consultant with research and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie who specialises in the energy storage supply chain.

Currently, the unit price of sodium-ion batteries for energy storage is about 60% higher than that of lithium-ion ones, but the gap is projected to narrow, China Central Television reported, citing analysis by the China Energy Storage Alliance, a Beijing-based non-profit.

China to lead the charge

Some entrepreneurs and researchers believe that sodium is a shortcut for other countries to reduce their battery dependence on China.

But it is Chinese companies that are poised to lead global production if the technology breaks into the mass market. Major Chinese battery makers have included it in their strategies to stay competitive in the long run, says Combs, meaning sodium-ion batteries are no longer a way to bypass their stronghold.

The “biggest difference” between companies in China and other countries is that the former can bring a technology from the lab to mass production much faster, Zheng says.

And because of the similarities between the two types of cells, says Logan, existing manufacturing infrastructure for lithium-ion batteries can be adapted to produce sodium-ion batteries, reducing the time and cost for commercialisation in China.

“The same synergies don’t necessarily hold true for other battery chemistries,” however, she adds.

One example is the all-solid-state batteries, which do not use liquid electrolyte to transport ions, the principle driving the current generation of batteries, says Mo Ke, founder and chief analyst of Beijing-based battery-research firm, RealLi Research. Therefore, it will have less reliance on the current industrial chain, Mo says.

A fleet of large factories devoted to making sodium-ion cells are now being built in China, some already in operation. In 2024, Chinese manufacturers announced plans to build 27 sodium-ion battery plants with a combined capacity of 180 GWh, according to Chinese thinktank Gaogong Industrial Research, including BYD’s upcoming 30GWh plant in Xuzhou.

The planned global sodium-ion battery capacity will exceed 500 GWh by 2033, and China is projected to account for more than 90% of that, Zheng says, citing Wood Mackenzie analysis.

Outside China, Natron Energy in the US and Faradion in the UK are forerunners. But it typically takes foreign companies much longer to build production lines and it will be hard for their capacities to compete with China’s, Zheng says.

In 2023 alone, Chinese firms collectively spent more than 55 billion yuan (£5.7bn, $7.6bn) on the research and development of sodium-ion batteries, according to Alicia García Herrero, an economist and senior fellow at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. This beats the $4.5bn (£3.4bn, $4.5bn) raised by all US battery start-ups cumulatively by 2023 on non-lithium battery solutions, she says.

Chinese companies’ incentive is simple, according to Combs: “Don’t lose market share, and future markets are included.” Yadea is already expanding operations in Southeast Asia, Latin America and Africa, where electric scooters are also popular, Zhou said in the talk show.

Yadea’s goal is clear: to mass-produce sodium-ion batteries and improve scooter charging infrastructure, according to Zhou, “so as to enable hundreds of millions of people to enjoy green transport”.