How did Egypt’s and Israel’s economies do in a year of Houthi attacks?

When Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps suggested connecting the Red and Mediterranean seas by building the Suez Canal, his idea was clear: a shorter shipping route from Asia to Europe and a source of income from transit fees.

The idea was welcomed by Egypt’s khedive, Ismail Pasha, and the Suez Canal opened in 1869. Since then, it has become one of the most important maritime routes in the world.

Uncertain seas

About 12 percent of the world’s trade passes through the Suez Canal, including about 40 percent of Asia-Europe trade.Diverting this much traffic onto a longer route has negatively impacted the global economy, Mamdouh Salama, an expert in energy and transport economics, told Al Jazeera.

“Ships taking the Cape of Good Hope route … add about 14 days to voyage time, which means higher costs for transporting goods in addition to higher insurance costs due to the increased risks to which ships are exposed,” he explained.

Shipping costs have more than trebled, according to some analyses.

Zian Zawaneh, a political economist and former adviser to the International Monetary Fund, said the lack of a clear end date for Houthi operations in the Red Sea makes things worse for shipping companies.

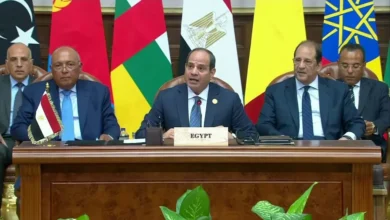

How Egypt has done

Egypt had looked to the Suez Canal as a source of revenue it could nurture, investing $8bn to make a large portion of it double-tracked to allow more and bigger ships to move through faster.

To raise capital for this, Egypt issued government bonds in 2014 with an interest rate of nearly 12 percent, the highest on the market at the time.

Work began in 2014 and was completed in just one year, the government wanting to get revenues quickly and raise morale by completing a megaproject.

When the project was opened in August 2015, the then-head of the Suez Canal Authority, Mohab Mamish, promised to raise revenues to $100bn a year.

The $9.4bn figure was the highest the canal has achieved in its history, Rabie said.

Zawaneh ties the losses Egypt has sustained to the fact that it signed a $35bn partnership with the UAE to develop a multipurpose megacity in Ras El-Hekma on its north coast.

How Israel did

The impact of the Houthi attacks on the Israeli economy has been severe, according to Abu Shehadeh.

That is the case especially because “Israel does not have natural resources and relies on imports to meet its various needs,” he said.

Abu Shehadeh explained that as the Israeli Red Sea port of Eilat has been practically at a standstill, the cost of getting goods to the Mediterranean ports of Haifa and Ashdod has risen enormously, which has increased costs for consumers.

Israel has tried to find alternatives, such as air transport or trucking overland via Jordan, but none was “enough to contain the problem”, Abu Shehadeh said.

Israel is also losing out on fulfilling its dream of becoming a regional centre for the production and export of liquefied natural gas given the difficulty and expense of getting large tankers to its ports.

This year, Israel has seen several monthly budget deficits rise above the 6.6 percent of gross domestic product the government tries to stay within.

Abu Shehadeh added that he observed a shift in Israeli society as the government prolonged and expanded its war. The increased pressure on people, he said, has resulted in “thousands of middle-class Israelis [emigrating], … including skilled workers, and this is another cost of this war”.