How a tribe brought back its sacred California condors

On a cloudy day in May 2022, following years of research, it was time for the Yurok Tribe to test whether its captive-bred condors were ready to live in the wild.

Two condors had been chosen, who happened to be “best buds”, says Tiana Williams, director of the Yurok Tribe Wildlife Department and member of the Yurok Nation.

The birds were clearly curious about the trap door which opened up in front of them to the wild. They took turns scooching forward on their perch and jumping back, until finally, one bird took the plunge.

“You could see one gearing himself up towards it, and he takes a couple of running steps to the edge, leaps out, and just takes to the sky and soars off,” remembers Williams.

The remaining bird followed seconds later. For the first time in 100 years, sacred condors were flying over Yurok land.

Williams has spent the last 16 years trying to bring back the scavenger birds to her homelands. “Growing up I didn’t know anything about condors, and that’s the near tragedy.”

The Yurok Tribe considers the condor a sacred animal, integral to their creation story. But the birds had been absent from Northern California, where the tribe lives, for so long that “they weren’t even part of the conversation anymore”, says Williams. “We were so close to completely losing this huge part of ourselves.”

California condors are the largest land birds in North America, with a wingspan of 9.5ft (2.9m) – that’s almost the same length as some compact cars. Condors can weigh up to 25lbs (11.3kg) and travel up to 200 miles (320km) a day searching for food, reaching speeds of 50mph (80km/h).

Historically, the California condor’s range stretched from California across the US to Florida, and from Northern Mexico all the way north to Western Canada. But by 1982, just 22 Californian condors remained in the world. The species had been all but wiped out by lead poisoning, illegal killing and the use of the pesticide DDT – which prevents condor eggs from hatching.

We were so close to completely losing this huge part of ourselves – Tiana Williams

The initial hurdle to saving the species was a desire to reduce human involvement, says Chris West, the Yurok Tribe’s senior wildlife biologist. “There were serious concerns [that] bringing them into zoos would result in the species going extinct in cages. Many believed it would be better to allow them to die out in the wild, on their own terms.”

It wasn’t even clear why the populations were crashing in the 1980s, adds West. “Or even if they could be bred in captivity,” he says.

Extreme lengths

Eventually, though, in 1987, the entire wild condor population was placed into a captive breeding initiative, the California Condor Recovery Program, in a bid to save it from extinction. Scientists realised the birds were being poisoned by lead ammunition used by hunters. As scavengers, they were feeding on animal carcasses that contained fragments of the ammunition.

Once the California breeding programme was underway, scientists found that condors in fact bred well in captivity. The next hurdle was figuring out how to reintroduce a “complex social scavenger” into the wild, says West. “They are so different from many other species that many new ideas and methods had to be developed. We had to learn and innovate as we went,” he says.

By the time the Yuroks got involved, California had made strides reintroducing the condor, with the first chick hatching in the wild in 2004. In 2008, there were more California condors flying free in the wild than there were in captivity, a first since the state programme began. As of 2022, there were 347 condors in the wild and 214 in captivity. But efforts were primarily focused on central California, northern Mexico and Arizona – a long way from where the Yuroks live in the misty redwoods on the California-Oregon border.

In the early 2000s, when elders of the tribe gathered to discuss what conservation efforts they should focus on, the first on their list were their fish – the Yuroks are, after all, known as salmon people. But when it came to land animals, the condor was at the forefront of everyone’s minds, says Williams.

Condors are called prey-go-neesh in the Yurok language, and feature prominently in tribal ceremonies – they’re considered to be messengers who carry prayers into the heavens. But “they hadn’t been part of our ecological system [for a long time] – – and they were at risk of disappearing from our spiritual system too”, adds Williams.

Trial and error

Determined to bring condors back to the landscape, the tribe created the Yurok Tribal Wildlife Programme in 2008, with condor reintroduction as the main focus. Williams began looking at some of the challenges the project would come up against – including educating the community.

“We had the usual kind of questions when you bring back an endangered species: ‘What’s it going to mean if they return?’,” says Williams. “We also had people who just didn’t know what a condor was. Questions like, ‘Do I need to worry about this giant 9.5ft-wingspan bird picking up my child or dog?’ Which by the way, you absolutely do not,” she says. (Condors don’t even have the appropriate “footwear” to do that, they don’t have sharp talons capable of carrying humans – plus, they’re scavengers, Williams explains.)

The tribe obtained four juvenile birds in 2022 from Oregon Zoo, which had reared the condors in their breeding facilities, and a further three from Los Angeles Zoo. The best time to receive condors to release, Williams says, is when they are between one and a half and two years old when the parents usually begin to nudge the juveniles out of their nests.

After years of working in tandem with the California Condor Recovery Programme, federal agencies and geneticists, the tribe released their first two condors in 2022. Tribal elders gave the pair nicknames – a ceremonial practice usually reserved for when a community member goes through a big life transition. The bird who left first was named “Point”, which means “the one who went out ahead” – a traditional name for leadership. The second bird was named “Nesquik”, which means “he returns” – a name signalling the return of condors to the landscape.

The Yurok Tribe set up a “condor cam” and hundreds of members watched the release through the live feed.

Such releases can take days – condors can be easily spooked, and the tribe has learned to “relax into condor time” and wait until they’re ready to leave through the open trap doors, Williams says. The moment the first pair finally left, though, was incredibly special, she says.

“I cannot describe the feeling that overtook me watching that. I put my hand on my chest, and just watched them in the sky. I managed to hold on until everybody [else] had left and then I just cried, because it was so overwhelming,” says Williams. “It was such a beautiful moment.”

Sandy Wilbur, a retired biologist who previously worked for the US Forest Service and was instrumental in setting up California’s condor programme, says the Yurok have gone about condor reintroduction “the right way”.

“They studied the literature enough to know that the habitat still looked good for condors, but that there would be some things to consider – like lead poisoning,” says Wilbur. “When they drew up their proposal, they agreed to an upfront evaluation of the possible impact of lead and committed to a long-term effort. All this took some time, but when they were ready, they were really ready.”

A success story

Condors, with their wrinkled, pinkish-orange heads fringed by a fan of black feathers, are bestowed with “a face only a mother could love”, says Williams. But they play an important part in the ecosystem. They’re scavengers, serving as the clean-up crew for the landscape.

Animal carcasses can be vectors for all kinds of diseases, and by feeding on these carcasses, the birds help to prevent disease outbreaks. The downside is it can lead to condors ingesting things they shouldn’t, such as lead ammunition fragments in animal carcasses. Condors have been described as “canaries in the coal mine”, due to their sensitivity to toxins and pollutants in the environment that impact many other wildlife species.

The Yurok Tribe has released 18 condors into the wild so far, over four rounds of releases. They’re doing great, says Williams. “It’s been really exciting to watch the flock expand and change in their dynamics.” The first couple of cohorts stayed close to home, only exploring within a 30-mile (48km) radius. Now the birds wander as far as 95 miles (152km) away, she adds.

“It’s awesome to see these young birds who’ve literally never flown in their life because they were reared in facilities with limited flight space, starting to learn the ropes and how to use the landscape to their advantage,” says Williams.

Carbon Count

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 0kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view.

Challenges ahead

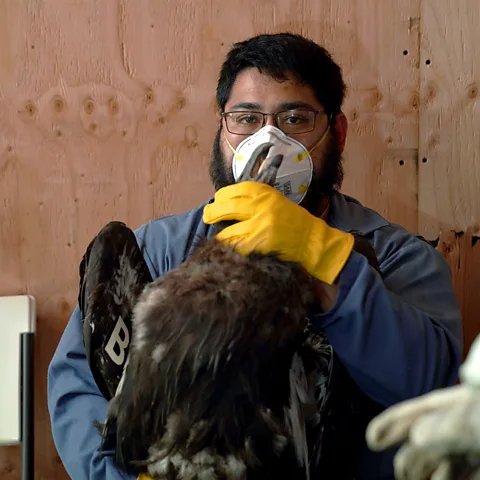

The tribe has a release and management facility to monitor the birds for the foreseeable future – many challenges remain before they become a fully self-sustaining population. The birds are brought back into the facility twice a year for check-ups to ensure they are doing well, and to check the transmitters they’re fitted with.

Williams acknowledges that some people consider them to be running a “big wild zoo” because of the heavy level of management of the birds, but the tribe takes precautions and limits human interaction as much as possible. “When we observe them, it’s in silence. We have a mirror where we can see them but they can’t see us. If we clean their water or give them carcasses, it’s at nighttime with a red head lamp so they can’t see us clearly. We don’t want them associating humans with food,” she says.

The intense management is needed because of the lead exposure risk. Lead poisoning remains a “significant threat” to the reintroduced birds, and the birds can be medically treated if they are found in time. One 2012 study collected blood samples from condors that had been released into the wild and found that 30% of samples indicated lead exposure.

When they were ready, they were really ready – Sandy Wilbur

“The condor’s apparent recovery is solely because of intensive ongoing management,” the study concluded, adding that the “only hope” of achieving a true recovery depended on the elimination of lead poisoning. A more recent study, published in 2023, came to the same conclusion, and found that copper-based ammunition could be used by hunters as a safe alternative.

In 2019, California banned the use of lead ammunition on live animals, but it is legal to purchase for other uses, such as target shooting. It’s extremely difficult to quantify to what extent it is still being used, says West.

All the Yurok condors have GPS units on them, which allows the tribe’s biologists to learn where a bird has travelled recently – and where it could have picked up lead. “What we are finding is that there is little now being picked up in much of condor range in remote forested areas,” says West. “A lot is within ranching and farming areas, timber harvest areas and other working landscapes that are not necessarily being hunted for game animals,” he says.

Recreational hunters, West continues, are doing a “fairly good job” at transitioning to non-lead ammunition. The issue lies with land managers who do not necessarily have access to information about changes in laws about the use of non-lead ammunition, he says. “Much of this sort of management is also reliant on the classic .22 long rifle round. This round is notoriously difficult to find in a non-lead option.”

West believes the key to a true, sustainable condor recovery is education. “The only way to combat a lack of information is to reach out to these communities and empower them with that information,” he says. “If [the public] all make the transition to non-lead ammunition, our intensive management efforts could virtually stop overnight.”

Remedying this single issue should allow condors to “again have a meaningful place in modern ecosystems”, says West.

In the meantime, the Yurok programme will reintroduce new birds to account for any killed by lead toxicity, although so far there haven’t been any mortalities.

Despite the challenges, the birds are becoming part of the Yurok’s narrative again, appearing in local art, jewellery – and even on an aeroplane the tribe uses for data collection.

“I have a six-year-old daughter,” says Williams, “and condors have been part of her whole life. One of her favourite games growing up was pretending she was a baby condor and I was condor mum. So it’s just part of her story in a way it could never be for me,” she says. “The condor is not only here in reality, but they’re here in our hearts again.”