Homes built with clay, grass, plastic and glass: How a Caribbean island is shying away from concrete

On the island of Trinidad, houses are being built using upcycled materials to make them more climate resilient.

When Erle Rahaman-Noronha decided to try his hand at farming in 1997, the land he settled on in Freeport, like much of Trinidad’s farmland, had been focused on monoculture – a remnant of the colonial plantations that scarred the region’s history.

“There was just a citrus tree every 20ft (6m) – none of these big trees were here,” he says, gesturing around him. Now the 30 acres (12 hectares) more closely resembles a forest, dotted with structures built out of repurposed materials.

Rahaman-Noronha hasn’t just reforested his land; he is passionate about ensuring the buildings on his farm are sustainable too. As you enter the farm a concrete house greets you – one of the older buildings on the land. But every other structure has touches of the earth. Clay, harvested from the land nearby; timber from the trees further back on the farm; repurposed glass bottles of all colours that glitter as the light hits them; rounded formations that only hint at the old, upcycled tires buried underneath to provide structure; and textured walls containing patchworks of dried grasses.

The farmer is embracing the old Trinidadian ways of building, when residents would use what was available to them, rather than mass importing materials. Not only is he putting waste products that would otherwise end up in landfill to use, Rahaman-Noronha is employing building styles that provide resilience against the island’s changing climate.

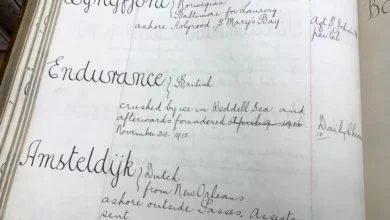

Wa Samaki Ecosystems This dragon bench is made from clay and decorated with upcycled metal (Credit: Wa Samaki Ecosystems)Wa Samaki Ecosystems

This dragon bench is made from clay and decorated with upcycled metal (Credit: Wa Samaki Ecosystems)

The effort is part of a project called Wa Samaki Ecosystems, a permaculture non-profit founded by Rahaman-Noronha who wanted to raise the profile of regenerative farming in the Caribbean and educate residents on how to practice sustainability while rehabilitating the spaces around them. “The long-term idea of having this site was to educate people on the environment, and to live in balance with nature,” he says.

A concrete culture

Much of the architecture on Wa Samaki bears the creative handprint of Wa Samaki’s eco-architect and sculptor, Celine Ramjit. Sculptural forms of cosmic bodies, animals and mythical creatures dot the landscape alongside the unique infrastructure, all constructed using a process called earth building – using materials available from the ecosystem. It means each constructed space has its own personality – and a greener footprint.

It’s a far cry from the increasingly common standard of building in Trinidad, where much of modern construction project an image of sterile uniformity. Ramjit notes that today, a lot of building choices have to do primarily with budget and accessibility of materials. “It comes down to education too,” she says. “Not considering where materials are coming from and how they are built.”

The long-term idea of having this site was to educate people on the environment, and to live in balance with nature – Erle Rahaman-Noronha

For a quick build, there isn’t as much time put into observing the environment: patterns of rainfall, plant and animal life, where the wind blows. “It’s these things that we have been disconnected from.” Instead, she says, it’s common to level the ground, remove any trees and start the build with a blank slate, without considering what is already there and how that can be integrated into the design. With deforestation and loss of native species being a widespread environmental issue, the practice of clearing what exists and creating something entirely new can have wider ripple effects on the land, like causing increased land slippage on slopes.

This disconnection from the environment is a feature of the “concrete culture” that became prevalent in Trinidad in the 1900s. Asad Mohammed, director of the Caribbean Network for Urban and Land Management, attributes this to “the impact of Western architectural inputs that have little relevance to the context we live in”. He describes a “modernistic style of square buildings” that are not climate-adapted to the intense heat of the dry season or the hurricanes and flooding of the wet season.

Learning from the past

These concrete boxes weren’t always the norm in the Caribbean. Throughout Caribbean history, there were various architectural styles that employed what Mohammed refers to as “good tropical design”. He describes European-style timber houses, with adaptations to the regional climate like shuttered windows that could be sealed off in stormy weather, and awnings to protect from the heat of direct sunlight. Now, he says, these have been replaced in popularity by flat glass windows that often have to be perpetually closed to avoid exposure to direct sun and rain, which then means the building has to be air-conditioned.

In fact, the first homes in the region would have had no windows at all, or even walls. Tracy Assing, a member of the First Peoples Community in Arima, and director of the documentary The Amerindians says that for her ancestors, the oldest structures would have consisted of wooden beams with thatched roofs, and were mostly open to the air. “More like a shelter, with a sort of attic situation,” she says. They were seasonal dwellings, built to be easily returned to the earth and rebuilt when needed. “Mud was a technological advancement.”

While indigenous groups in the Caribbean were using clay to build smaller structures like ovens in pre-colonial times, it would be later before this technique would be applied to housing, Assing explains.

But by the 1600s, Spanish colonial influence combined with Indigenous techniques would have led to the popularity of wattle and daub mud structures known as tapia, which most closely resembles the building technique used today at Wa Samaki. Historian Glenroy Taitt, in a paper on the Tapia Method of Construction, describes the tapia house as an oval-shaped shelter with a wooden frame and a mixture of clay, water and grass used for walls, and a thatched roof of palm leaves.

Even though these types of buildings could be found across the country well into the 20th Century, Taitt writes that: “The tapia era ended around the 1940s…not only did people stop using tapia to build their houses, but they also began to see the material and the method as low-class and primitive.”

Houses from this bygone era are now hard to find, and can only be accessed in a select few places like the Avocat Mud House Museum. It was built in 1885 and stands as a record of the construction methods of the past, using techniques further popularised by the Indian immigrants that migrated to the Caribbean during the period of indentureship – although its caretakers say they are struggling to maintain it as the nearby hillside that was their main source of clay no longer exists.

Stepping into the century-old home, one can feel the immediate drop in temperature that is a signature of clay-based builds. As clay is more porous than concrete, it traps moisture which then evaporates and pulls heat from the surface as it goes. With climate change causing all-time heat records across the Caribbean, a comfortably cool room in the height of midday sunlight is a surprising feat in a structure with no windows, fans, or air-conditioning.

Climate-adapted construction was a feature of Caribbean architecture, and as weather patterns are changing across the globe, and particularly affecting these small Caribbean states, there is an increasing need to look to the successes of these older architectural styles, while incorporating advancements of the modern world. From the tapia clay and grass houses, to the wooden European colonial structures with their high ceilings and open airways, each stage of the Caribbean’s history has been reflected in the style of architecture constructed at the time.

When Trinidad and Tobago became an independent nation in 1962, it had to contend with what this meant for its national identity–and its buildings. Trinidadian architect Sean Leonard speaks on this grappling with identity: “Post-independence, part of defining a way forward for this new country state was deciding what our buildings should be like.” In urban settings, like the areas Leonard usually works in, making greener changes might mean something entirely different from what is being done in a rural space like Wa Samaki.

CARBON COUNT

The emissions from travel it took to report this story were 20kg CO2. The digital emissions from this story are an estimated 1.2g to 3.6g CO2 per page view. Find out more about how we calculated this figure here.

As he engages with corporate clients, who may not consider tropical design a high priority, moving the needle could be as small as utilising a more traditional style of window to better pull in cool air from the outside, or leaving a patch of earth unpaved to allow rainwater to be absorbed into the soil rather than running into the already overworked drains of flood-prone Port of Spain.

Another climate adaptation used throughout Caribbean history is building structures raised off the ground, which helps circulate cool air in the dry season and protects from flooding in the wet season. Leonard describes this as a technique used throughout Trinidad’s history that he still employs today, and it can be used both in urban settings or in farmland like Wa Samaki. For clay-based structures like the ones Ramjit is building, being raised off the ground is a necessity to protect the clay from absorbing too much moisture from the earth.

Repurposing waste

Traditional techniques and materials like grass and clay aren’t the only ones being utilised at Wa Samaki– they also use discarded materials to reduce waste. An on-site gazebo is made from bamboo and teak harvested from the land. Discarded tyres collected from neighbours are filled with plastic bottles and other plastic waste items before being covered over with sand and clay to create seating and walls in the decorative shape of a writhing dragon.

The roof is covered in old recycled advertising banners and piece of a water tank, the other half of which is used to house some of Rahaman-Noronha’s fish (Wa Samaki means “Of The Fish” in Swahili, a nod to his birthplace of Kenya). Across other builds on the farm, multi-coloured glass bottles inset into walls provide an avenue for streams of light and colour. Without their intervention, these materials would have likely ended up in one of Trinidad’s waste dumps, leaching chemicals into nearby environments like the Caroni Swamp Nature Reserve.

Across Wa Samaki, the team has planted vetiver, a multipurpose plant that actually can be used to treat leachate from chemicals in soil. On the farm, they use it to stabilise the banks of their ponds to avoid land slippage – but it is also one of the primary ingredients in their clay builds. Ramjit uses it in shreds to bring structure to earthen walls. The grass is harvested and dried, and its long, sturdy blades provide the perfect web to hold a clay structure together.

But Ramjit stresses the importance of experimenting with what grasses are available, rather than trying to source a specific type. Rice straw is also commonly used at Wa Samaki, but even lawn grass could be helpful as a binder for a clay mixture used to construct walls. In lieu of having fixed ‘recipes’ for what her construction materials should be, she tests and experiments with whatever is on hand, and encourages others to do the same.

Throughout the process, there is an underlying idea of having curiosity towards your surroundings, observing and collaborating with the natural world instead of seeking to bend them to your control. Assing describes a similar philosophy passed down through her community, of “working with the environment, instead of imposing yourself on it”. This collaborative approach could be the key, not only to building sustainable structures that borrow from both the past and present, but changing an entire culture of how humans think of their relationship with the land.

Whatever environment a structure is being constructed in, the core ideas remain the same – look around you, see what is there, and consider how you might be a part of it, rather than replacing it. For the team at Wa Samaki, a changing planet is not a cause to lose hope, but to consider all the knowledge and resources available to help restore balance to the place in which you live.