Henry Kissinger: 10 conflicts, countries that define a blood-stained legacy

To some, he was a titan of foreign policy, the Holocaust survivor who built a glittering career as the top diplomat of the United States and national security adviser during Presidents Richard Nixon’s and Gerald Ford’s administrations, leaving an enduring mark on history.

But to others, Henry Kissinger was a war criminal, whose brutal exercise of realpolitik left a trail of blood around the world – an estimated 3 million bodies in far flung places from Argentina to East Timor.

As the late British author and journalist Christopher Hitchens once wrote: “Henry Kissinger should have the door shut in his face by every decent person and should be shamed, ostracised, and excluded.”

Here are 10 nations, regions and conflicts that Kissinger intervened in, leaving an often blood-stained legacy that in many cases still lives on.

Vietnam

Kissinger won a Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating a ceasefire in Vietnam in 1973. But that war might actually have ended four years earlier had he not enabled Nixon’s plan to “monkey wrench” President Lyndon B Johnson’s peace negotiations. In 1969, Nixon was elected president, and Kissinger was promoted to the role of national security adviser. The prolonged war cost the lives of millions of Vietnamese, Cambodians and Laotians.

Cambodia

Kissinger’s expansion of the war set the scene for the genocidal rule of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, which seized power from a US-backed military regime and went on to kill a fifth of the population – two million people. Cambodians had been driven into the hands of the communist movement by Kissinger and Nixon’s carpet-bombing campaign, which killed hundreds of thousands of people. To this day, people are still dying from unexploded US ordinance.

Bangladesh

In 1970, Bengali nationalists in what was then known as East Pakistan won elections. Fearing a loss of control, the military government in West Pakistan launched a murderous crackdown. Kissinger and Nixon stood staunchly behind the slaughter, choosing not to warn the generals to hold back. Motivated by Pakistan’s usefulness as a counterweight to China and to Soviet-leaning India, Kissinger was unmoved by the killing of 300,000 to three million people. Captured in a secret recording, he voiced disdain for people who “bleed” for “the dying Bengalis”.

Chile

Nixon and Kissinger disapproved of Salvador Allende, a self-proclaimed Marxist, who was democratically elected as Chile’s president in 1970. Over the ensuing three years, they invested millions of dollars into fomenting a coup. Then-CIA chief William Colby told a secret 1974 hearing of the Armed Services Special Subcommittee on Intelligence in the House of Representatives that the US government had spent $11m to “destabilise” Allende’s government. That included $1.5m that the CIA funnelled into Santiago newspaper El Mercurio, which was opposed to Allende. CIA operatives also forged links with the Chilean military. In 1973, General Augusto Pinochet came to power in a military coup. During his 17-year-long rule, more than 3,000 people were disappeared or killed, and tens of thousands of opponents were imprisoned. As Kissinger told Nixon: “We didn’t do it. I mean we helped them.” More than three decades after Pinochet was finally forced out of office, Chile is still grappling with the former dictator’s US-enabled legacy.

Cyprus

Home to Greek and Turkish populations, Cyprus had seen ethnic violence throughout the 1960s. In 1974, after a coup by Greece’s ruling military government, Turkish troops moved in. Kissinger effectively encouraged a crisis between the two NATO allies, advising newly installed President Ford to appease Turkey. “The Turkish tactics are right – grab what they want and then negotiate on the basis of possession,” he is reported to have said. Together, the Greek coup and the Turkish invasion resulted in thousands of casualties.

East Timor

In 1975, Kissinger greenlit President Suharto of Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor, a former Portuguese colony moving towards independence. During a visit to Jakarta, Kissinger and Ford told Suharto, a brutal dictator and close ally in the battle against communism, that they understood his reasons, advising him to get it over and done with quickly. The next day, Suharto moved in with his US-equipped army, killing 200,000 East Timorese.

Israel

When the October War in 1973 broke out when a coalition of Arab nations led by Egypt and Syria attacked Israel, Kissinger led the Nixon administration’s response. He pushed back against the Pentagon’s attempts to delay the shipment of arms to Israel, rushing through weapons that helped the Israeli army reverse early losses and reach within 100km (62 miles) of Cairo. A ceasefire followed. His shuttle diplomacy between Egypt, other Arab nations and Israel is often credited with paving the way for the eventual signing of the Camp David Accords in 1978. By then, Kissinger was out of office, but in 1981, he explained that at the heart of his diplomacy in the Middle East was a simple policy objective — to “isolate the Palestinians” from their Arab neighbours and friends.

Argentina

No longer in office after Jimmy Carter succeeded Ford as president in 1976, Kissinger continued to endorse murder, giving his seal of approval to the neo-fascist Argentinian military, which had overthrown the government of President Isabel Peron that same year. The military government waged a dirty war against leftists, branding dissidents as “terrorists”. During a visit to Argentina in 1978, Kissinger flattered dictator Jorge Rafael Videla, lauding him for his efforts in combatting “terrorism”. Videla would oversee the disappearance of up to 30,000 opponents. About 10,000 people died during the military’s rule, which lasted until 1983.

Southern Africa

During most of his time in the Nixon and Ford administrations, Kissinger didn’t appear to have given Africa much thought. But in 1976, as his time in office drew to a close, he visited South Africa, bestowing political legitimacy on the apartheid government shortly after the Soweto uprising, which saw Black schoolchildren and others gunned down by police. While he did force Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith into accepting majority Black rule, he cleaved close to South Africa’s apartheid government in its support for Unita rebels fighting the Marxist-Leninist People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola. That war lasted 27 years, one of the longest and most brutal of the past century.

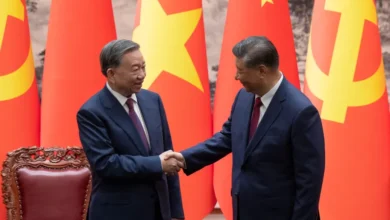

China

Kissinger is often praised for brokering the US-China detente. After an initial visit to Beijing in 1972, he helped re-establish diplomatic ties in 1979. Chinese President Xi Jinping has described him as an “old friend”. However, the protesters who camped out at Tiananmen Square in 1989 remember him less fondly. In the immediate aftermath of the massacre – which killed anywhere between several hundred and several thousand people – he offered a glimpse of the cold, hard realpolitik that characterised his approach to diplomacy. The crackdown, he said, was “inevitable”. “No government in the world would have tolerated having the main square of its capital occupied for eight weeks by tens of thousands of demonstrators,” he said. China, he said, needed the US, and the US needed China.