Has Australia cleaned up its act on climate?

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese came to power last year promising the country would leave the climate “naughty corner”.

Long considered a laggard, Australia would now cut emissions, become a renewable energy powerhouse and force the biggest polluters to clean up their act, the new leader declared.

“I want to join the global effort,” Mr Albanese said, minutes after his victory speech.

It is now a year since he legislated Australia’s first ever emissions reduction target – so, has he delivered?

Resolving the ‘climate wars’

Until recently, acknowledging and tackling climate change proved a hugely contentious issue in Australia – famously playing a role in toppling three prime ministers in a decade.

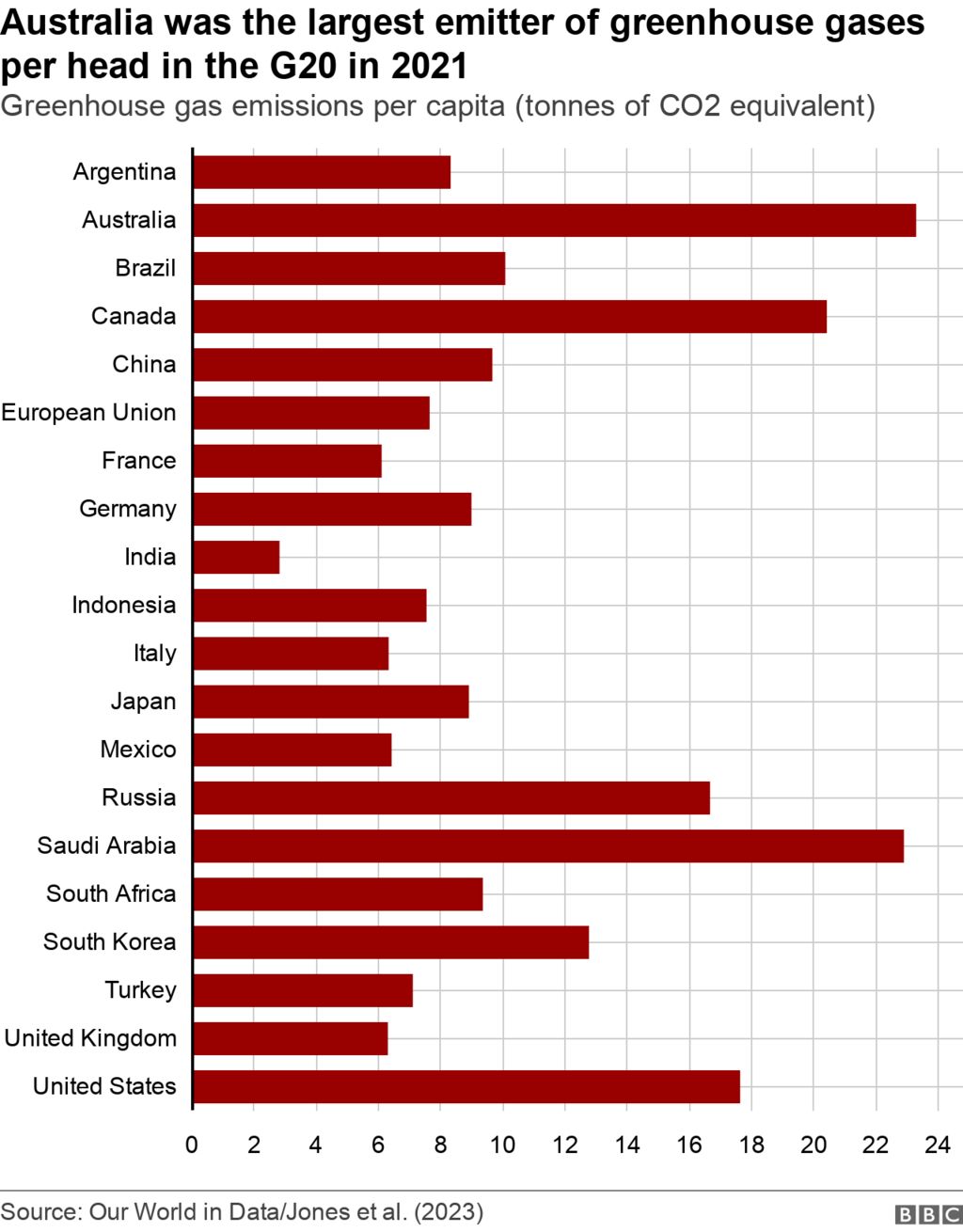

The country is one of the world’s biggest polluters per head of population, and it has failed to make any significant cuts to its core emissions despite signing up to global pledges.

But Australia is also a nation where the effects of climate change have become devastatingly obvious.

In 2022 – the so-called “climate election” – there was a historic surge in support for candidates pledging urgent action, and the issue was a major factor in the demise of yet another prime minister, Scott Morrison, whose conservative government had been in power for nine years.

“Together we can end the climate wars,” Mr Albanese said at the time.

The election of his government made a huge, overnight difference to Australia’s international standing, experts say.

Many world leaders expressed relief at – or alluded to – the fact Australia had a new leader who appeared serious on climate change.

Fiji’s then PM Frank Bainimarama, whose country is among the most at risk from rising seas, welcomed Australia’s plan to “put the climate first”, while the UK’s Boris Johnson said he looked forward with working with Mr Albanese on making the world a “better” and “greener” place.

Professor Mark Howden – a vice chair of the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – noted a change in attitude among the science and business communities too.

“I used to get accosted by people at conferences… people were sort of critiquing Australia’s position and wondering why we weren’t doing more,” he said.

“These days, they’re very welcoming.”

Big strides taken – but concerns linger

Mr Albanese’s government has enshrined into law an emissions cut target of 43% by 2030, up from 26-28%. That difference is equivalent to eliminating emissions from Australia’s entire transport or agriculture sectors.

It has also negotiated the introduction of a key plank of its plan to achieve that goal – a “safeguard mechanism” that acts as a carbon cap for the country’s biggest emitters.

“[That] was really the first new piece of legislation aimed to actually driving down emissions in Australia for more than a decade,” Climate Council researcher Simon Bradshaw said.

“We’ve got ourselves back in the game.”

The government is also looking to incentivise emissions cuts on a consumer level, through things like an electric vehicle policy that is still to be detailed.

Public concern over the government’s actions on climate change has fallen – 31% of Australians believe they are doing too little, down from 44% the year before, when the Morrison government was in power.

But there’s still “an appropriate level of cynicism” towards Australia and its climate efforts, experts say.

Its new 2030 target is not enough to meet the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5C. The world has already warmed by 1.1C but experts say they’re optimistic that dramatic and rapid changes can still save the planet.

However Australia’s target is also weaker than many of its international peers, such as the US or UK.

“We’re not laggards anymore, but neither are we leaders,” Prof Howden says.

Critics are chiefly concerned that the government has refused to outlaw new coal, oil and gas projects.

New projects will not just be a hurdle for domestic emissions targets. It is the global implication that is most grim – Australia is one of the world’s biggest fossil fuel exporters.

The IPCC says new fossil fuel projects are not compatible with the aims of the Paris Agreement, and in fact, existing infrastructure must be urgently phased out.

But the Australian government has already greenlit three new coal mine projects – including one just last week.

That Australia persists with new fossil fuel projects despite declaring a new era on climate is “extremely reckless” and “no doubt confusing” to others across the globe, Dr Bradshaw says.

“There are questions being asked by our international peers, as they should be,” he says.

“The science here is unequivocal… it compels us to leave our fossil fuels in the ground. Every new project that is developed and every tonne of carbon we burn is pushing us closer to catastrophe.”

Long road ahead

Experts say there is still plenty more the government could – and must – do to drive its emissions down.

At the top of those calls is a comprehensive price on greenhouse gas emissions, like those in place in the UK, Canada and Scandinavia.

“Almost every economist across the globe would say [that] is the best and most efficient way of reducing emissions,” says Prof Howden.

“In an ideal world, that would be what we do next [but] we’re living in a world where politics has made that a toxic ground to occupy,” he says, referring to a carbon tax furore that played a big role in the downfall of former Australian leader Julia Gillard in 2013.

A carbon price isn’t part of the government’s official climate policy, and Mr Albanese has previously suggested such a measure wouldn’t be necessary anymore thanks to cheaper renewable energy.

But there’s room for improvement there too, experts say.

Australia is one of the sunniest and windiest countries in the world, and is surrounded by seas which could be used for hydro-electric power. But currently only about 30% of Australia’s electricity comes from renewable sources – significantly below than the UK, for example, which is far less blessed with natural resources.

Australia’s government has a lofty goal of making that 82% by the end of the decade. It envisages this will both drive down emissions and enable Australia to replace fossil fuel exports.

Others like Dr Bradshaw and the Greens party say reform to Australia’s environment laws so that they factor in the climate impacts of developments is desperately needed, pointing to recent mine approvals.

So while there is renewed optimism overall, so far there’s little actual progress in emissions cuts themselves.

With 2030 now only seven years away, the country’s emissions have dropped by about 21% against the 2005 benchmark it set, according to government figures.

But that is mainly because it is cutting down fewer trees – which capture and store carbon. That’s something expert say often hides true emission trends.

In reality, the country’s gross emissions have barely budged – dropping by just 1.5%.

“Having lost many years, we’re really just at the start of this journey… it does take time to turn the ship around. We can meet those targets… but it does mean accomplishing a lot early on in this decade,” Dr Bradshaw says.