Flax: The historic plant making a comeback

Flax once defined Northern Ireland, with a thriving linen industry.

But changing consumer habits saw that industry decline massively in the mid-20th century.

Now, the plant is being looked at as a tool to restore soil health and even help decarbonise manufacturing.

And it may be a potential diversification route for smaller farms, as demand grows for sustainable fibres.

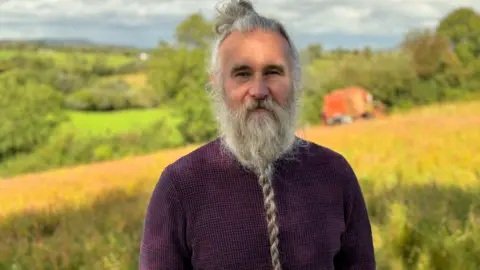

Helen Keys and her sculptor husband Charlie Mallon began growing flax when they couldn’t source Irish linen bags for Charlie’s artwork.

The crop was grown on Charlie’s family farm in County Tyrone in the past.

Helen’s eyes have been opened to the plant’s potential.

“There is a real resurgence and interest now in natural fibres because we have to look at how we are going to replace things like carbon fibre, fibreglass,” she said.

“And natural fibres have a big role to play in decarbonizing industry.”

Fibre crops like flax and hemp have a high nutrient uptake from the soil and a minimal requirement for fertiliser.

They are rotational crops, which can be alternated with other arables like vegetables.

For Professor Mark Emmerson, from the School of Biological Sciences at Queen’s University Belfast, that means they could play a part in tackling the blue-green algae problem in Lough Neagh by reducing the nutrient burden on the land.

“I would see flax production and veg production as part of a just transition that enables farmers to look at what they’re doing on the farm and where it’s appropriate – and only where it’s appropriate – to look at putting an acre or two, or a hectare or two, of land under flax or veg production.”

While he is realistic, he is also optimistic about the potential of different applications of flax.

“I’m not sure this is a solution for the big dairy farms,” he said.

“But of the 26,000 farms in Northern Ireland, 78% of them are considered very small, which means that they have less than one person working the farm on any given week and those individuals are having to go off-farm to maintain a second job to maintain the farm.

“So, you know, an acre of flax in the mix might actually enable those farmers to stay on farm and work the farm so that the farm is able to pay for itself.”

A community gathering – a meitheal, in ancient Irish tradition – was held at the end of August, bringing volunteers from around the island of Ireland to Helen and Charlie’s farm near Cookstown to finish the flax harvest.

Self-confessed “flax nut” Kathy Kirwan travelled from Clonakilty in County Cork to take part.

She has fallen in love with the “circular” nature of the plant.

“Nothing goes to waste, absolutely nothing. Like, 50% of the plant when you’re processing it comes out as shives (woody material) and that’s used for composite.

“We made paper, so no part of it actually goes to waste whatsoever.

“It just fits into the values of protecting the earth, protecting nature, and it needs no pesticides or herbicides.”

She has worked with Malú Colorín, from Fibreshed Ireland, which is part of a global movement that focuses on regenerative fashion using locally grown fibres.

“Linen is kind of like the cream of the crop of what you can do with flax, but then you can also create less fine fibres, such as rope as well,” she said.

“And then of course, if you get into the shive, the by-product, you can get into composites and oil from the seeds and wax and stuff.”

Crafter Cathy Kane and her husband are working to build their own self-sustainable homestead in North Cork.

Where they live is called Sliabh Luachra, which translated from Irish means rushy mountain.

“It’s very agrarian agriculture, forestry, that kind of thing, so flax is perfectly suited.

“Flax is part of my crop rotation in my sort of vegetable garden rotation that I’m kind of planning in my head.

“And because I like working with fibre, I thought it’s perfect.”

For Gawain Morrison, founder of the Belfast climate initiative Brink! and organiser of the Flax Meitheal weekend, there is a sense of a desire for change.

“When you see something like this, where you’re bringing together people who are robotics engineers, composites, farmers, all coming together under the same umbrella to make a difference, that’s when you know a tipping point’s coming.

“Because everybody’s pointing in the same direction.”