Five new soft-furred hedgehog species discovered

Scientists have discovered five new species of soft-furred hedgehogs from South East Asia.

The revelation required several scientific missions to the animals’ tropical forest home to study them.

Researchers also re-evaluated specimens of the mammals which had been in museum collections for decades.

This detailed, biological spot-the-difference study revealed that two of the animals in the museums were new species to science.

Three others – that had been categorised as subtypes of one species – were confirmed to be sufficiently distinct from each other to be formally recognised as individual species.

One of the lead researchers, Dr Melissa Hawkins, from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (SMNH), said that the discovery showed the “amazing” diversity of life on our planet still to be revealed.

“We think we know about the natural world,” said Dr Hawkins, “but even groups like mammals – especially the little things that live in difficult-to-reach habitats – we really don’t know much at all.

“Finding animals like these could bring some attention to [rainforest] ecosystems that are very threatened,” she said.

What are soft-furred hedgehogs?

The animals belong to a group of hedgehogs called Hylomys, all of which live in South East Asia. There were previously only two known species, and this discovery brings the tally to seven.

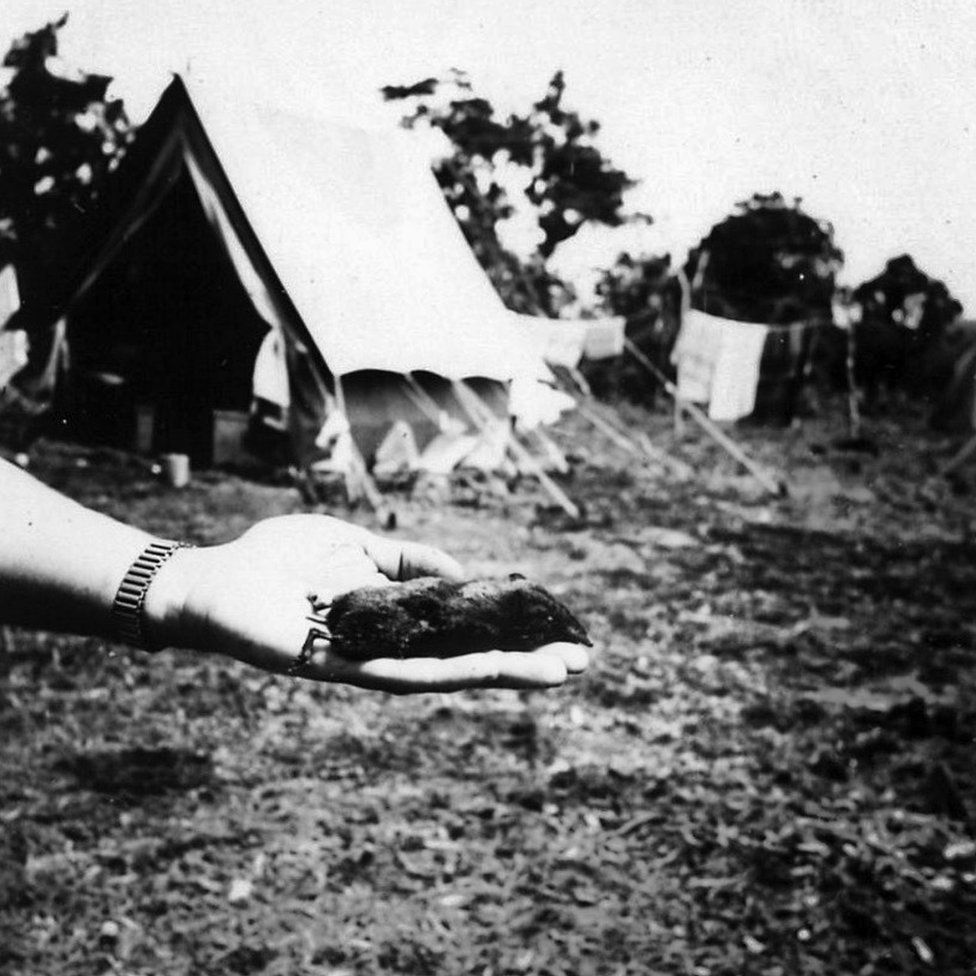

They are small, long-nosed mammals and, while they are members of the same family as the more familiar hedgehog, are furry rather than spiny.

Dr Arlo Hinckley, also from SMNH, said a discovery like this was “particularly important in South East Asia, which has the highest rates of deforestation in the world”.

How do you discover a new species?

This is challenging when you are studying what Dr Hawkins described as “little brown things” that live in dense forest.

To the non-expert eye, the diminutive mammals look alike, but the team found key differences in their genetic codes, and differences in their physical shape – particularly their heads and teeth.

“Their skulls are really cool – they’re tiny, but they have these really sharp teeth,” said Dr Hawkins.

“If they were bigger animals they’d be pretty scary.”

The scientists named one particularly long-fanged species – that they discovered in one of the museum collections – Hylomys macarong, a name derived from the Vietnamese word for “vampire”.

As well as studying the animals in the wild, the researchers examined specimens from a total of 14 different natural history collections across Asia, Europe and the US.

The two newly discovered species – Hylomys vorax and Hylomys macarong – were discovered in the collections of the Smithsonian and Drexel University in Philadelphia, where they had remained in drawers for several decades.

“We kind of say we can time travel as museum curators,” said Dr Hawkins.

“We can pop down the hall, look in the collection and go anywhere in the world.”

The researchers gathered enough genetic material from the three other species, which were previously categorised as subspecies, to reveal that they were biologically distinct.

Each different Hylomys species appears to live in a slightly different habitat – some in the lowland forests and some at higher altitudes.

Finding animals that are the result of millions of years of evolution and are unique to one area of tropical forest, said Dr Hinckley, “is a bit like the inclusion of a Picasso in an art gallery or the discovery of an archaeological site in a city”.

“It gives these places additional value, and hopefully funding to protect such an important heritage.”