First-ever images prove ‘lost echidna’ not extinct

Scientists have filmed an ancient egg-laying mammal named after Sir David Attenborough for the first time, proving it isn’t extinct as was feared.

An expedition to Indonesia led by Oxford University researchers recorded four three-second clips of Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna.

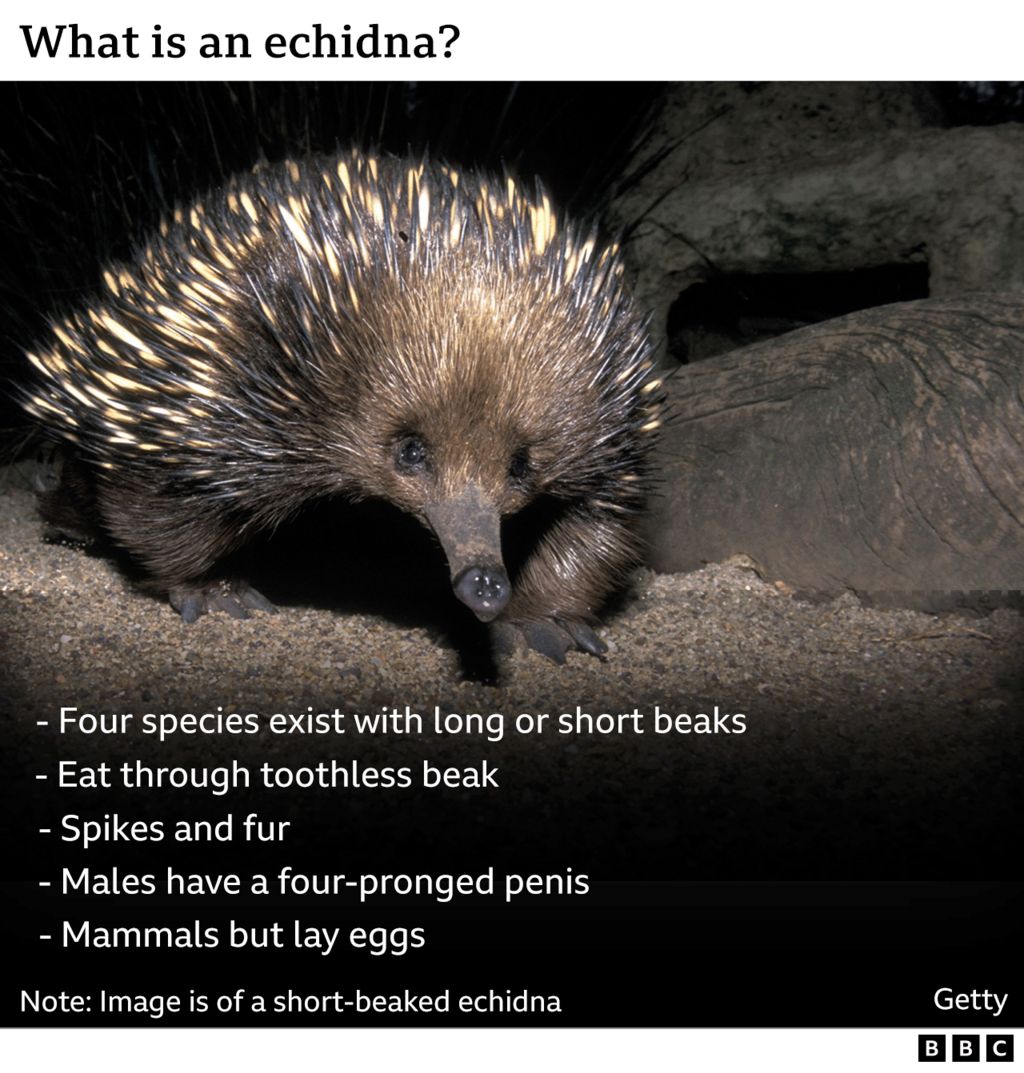

Spiky, furry and with a beak, echidnas have been called “living fossils”.

They are thought to have emerged about 200 million years ago, when dinosaurs roamed the Earth.

Until now, the only evidence that this particular species Zaglossus attenboroughi existed was a decades-old museum specimen of a dead animal.

“I was euphoric, the whole team was euphoric,” Dr James Kempton told BBC News of the moment he spotted the Attenborough echidna in camera trap footage.

“I’m not joking when I say it came down to the very last SD card that we looked at, from the very last camera that we collected, on the very last day of our expedition.”

Dr Kempton said he had been in letter correspondence with Sir David about the rediscovery and that he was “absolutely delighted”.

Dr Kempton, a biologist from Oxford University, headed a multi-national team on the month-long expedition traversing previously unexplored stretches of the Cyclops Mountains, a rugged rainforest habitat 2,000m (6,561ft) above sea level.

In addition to finding Attenborough’s “lost echidna” the expedition discovered new species of insects and frogs, and observed healthy populations of tree kangaroo and birds of paradise.

Aside from the duck-billed platypus, the echidna is the only mammal that lays eggs. Of the four echidna species three have long beaks, with the Attenborough echidna, and the western echidna considered critically endangered.

Previous expeditions to the Cyclops Mountains had uncovered signs, such as ‘nose pokes’ in the ground, that the Attenborough echidna was still living there.

But they were unable to access the remotest reaches of the mountains and provide definitive proof of their existence.

That has meant that for the last 62 years the only evidence that Attenborough echidna ever existed has been a specimen kept under high security in the Treasure Room of Naturalis, the natural history museum of the Netherlands.

“It’s rather flat,” Pepijn Kamminga, the collection manager at Naturalis, says as he holds it for us to see.

To an untrained eye it’s not dissimilar to a squashed hedgehog because when it was first gathered by Dutch botanist Pieter van Royen it wasn’t stuffed.

The importance of the specimen only became clear in 1998 when X-rays revealed it was not a juvenile of another echidna species but in fact fully grown and distinct. It was then that the species was named after Sir David Attenborough.

“When that was discovered, people thought, well, maybe it’s extinct already because it’s the only one,” Mr Kamminga explains. “So this [the rediscovery] is incredible news.”

The Cyclops Mountains are precipitously steep and dangerous to explore. To reach the highest elevations, where the echidna are found, the scientists had to climb narrow ridges of moss and tree roots – often under rainy conditions – with sheer cliffs on either side. Twice during their ascent the mountains were hit by earthquakes.

“You’re slipping all over the place. You’re being scratched and cut. There are venomous animals around you, deadly snakes like the death adder,” Dr Kempton explains.

“There are leeches literally everywhere. The leeches are not only on the floor, but these leeches climb trees, they hang off the trees and then drop on you to suck your blood.”

Once the scientists reached the higher parts of the Cyclops it became clear the mountains were full of species that were new to science.

“My colleagues and I were chuckling all the time,” Dr Leonidas-Romanos Davranoglou, a Greek insect specialist, said.

“We were so excited because we were always saying, ‘this is new, nobody has seen this’ or ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe that I’m seeing this.’ It was a truly monumental expedition.”

Dr Davranoglou broke his arm in the first week of the expedition but remained in the mountains collecting samples. He says they have already confirmed “several dozen” new insect species and are expecting there to be many more. They also found an entirely new type of tree-dwelling shrimp and a previously unknown cave system.

Gison Morib, a conservationist with Yappenda, a local non-profit that partnered with Oxford University on the expedition, said: “The top of the Cyclops are really unique. I want to see them protected.

“We have to protect these sacred mountains. There are so many endemic species we don’t know.”

Sacred mountains

Previous expeditions had struggled to reach the parts of the Cyclops Mountains where the echidnas live because of the belief of local Papuans that they are sacred.

“The mountains are referred to as the landlady,” Madeleine Foote from Oxford University says. “And you do not want to upset the landlady by not taking good care of her property.”

This team worked closely with local villages and on a practical level that meant accepting that there were some places they couldn’t go to, and others where they passed through silently.

The Attenborough echidna’s elusiveness has, according to local tradition, played a part in conflict resolution.

When disputes between two community members arose one was instructed to find an echidna and the other a marlin (a fish).

“That can sometimes take decades,” Ms Foote explains. “Meaning it closes the conflict for the community and symbolises peace.”

Dr Kempton says he hopes that rediscovery of the echidna and the other new species will help build the case for conservation in the Cyclops Mountains. Despite being critically endangered, Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna is not currently a protected species in Indonesia. The scientists don’t know how big the population is, or if it is sustainable.

“Given so much of that rainforest hasn’t been explored, what else is out there that we haven’t yet discovered? The Attenborough long-beaked echidna is a symbol of what we need to protect – to ensure we can discover it.”