Drought risk to England regions after dry February, scientists warn

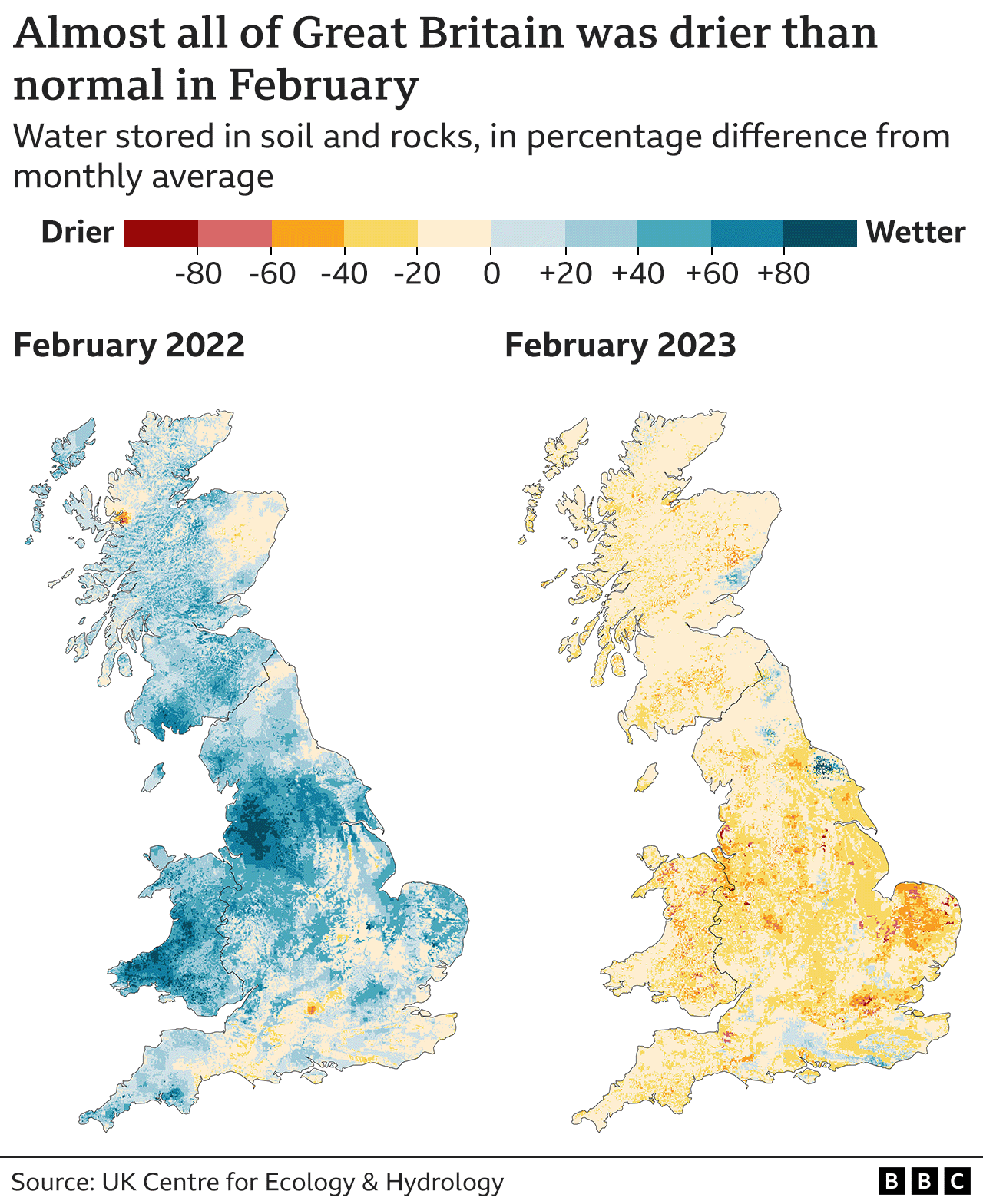

It might feel wet this week but experts are warning that parts of England need unseasonable rainfall to compensate for an abnormally dry winter.

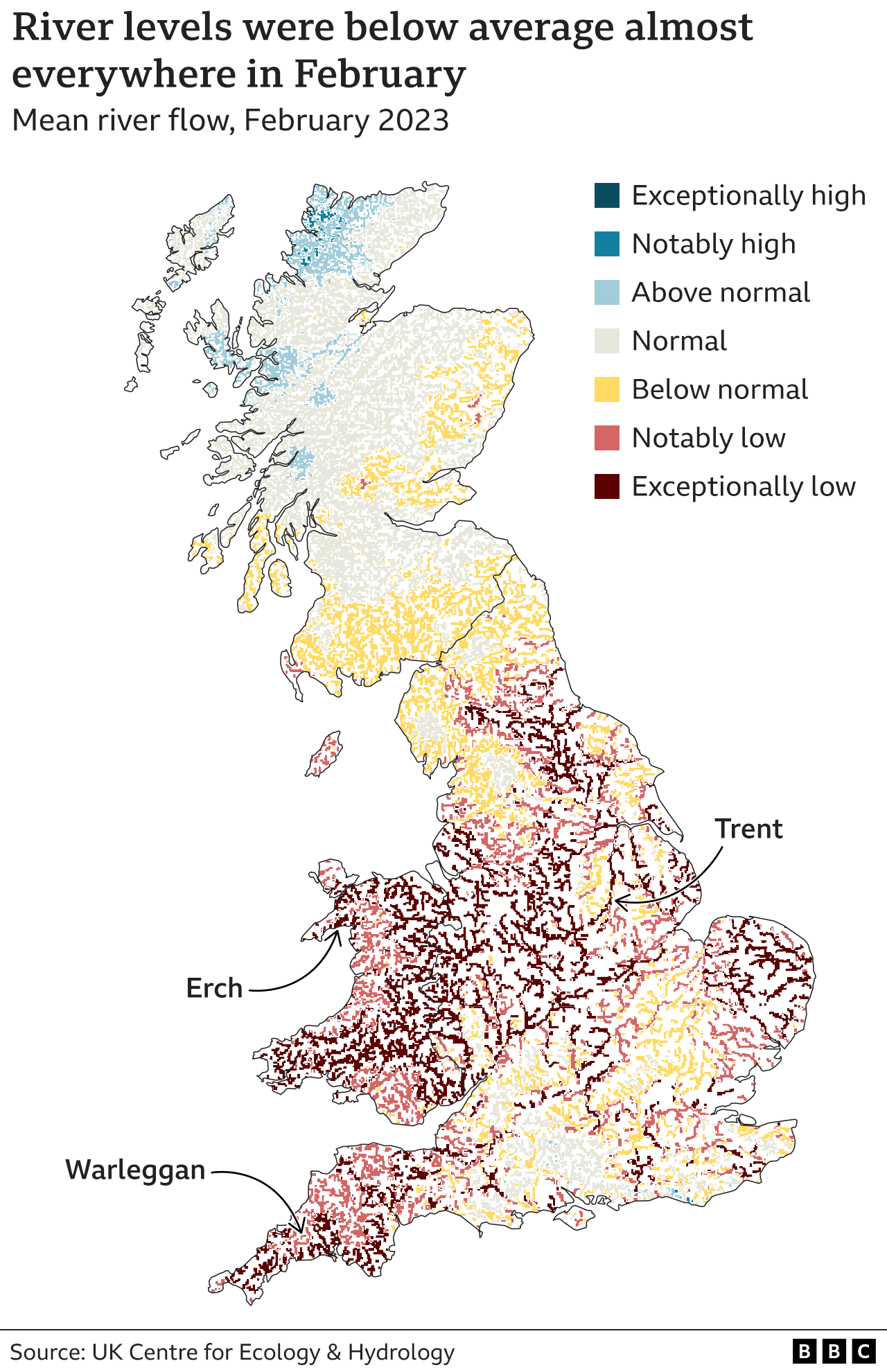

Rivers in some of England and Wales ran their lowest on record for February, according to data from the UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology.

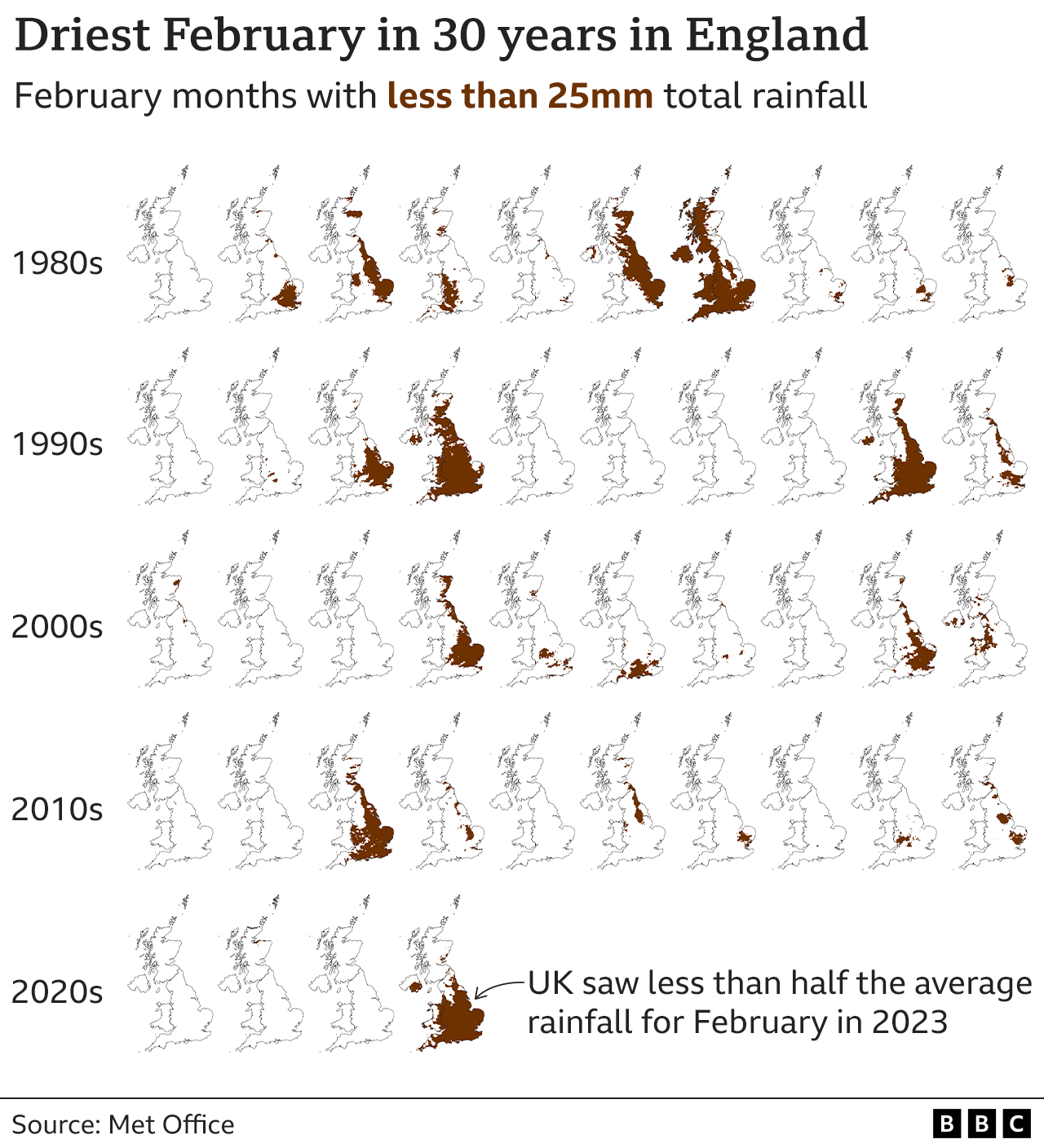

England had its driest February for 30 years, according to the Met Office.

Rivers and reservoirs that supply drinking water and feed crops rely on winter rain to top up before spring.

Without “unseasonably sustained rainfall” in the coming months, South West England and East Anglia are at risk of drought, the UKCEH explains.

“The wet weather and snow during the first two weeks of March has led to an increase in river flows and rewetting of the soils [but] some areas of England were starting March with below-average groundwater levels or below-average reservoir stocks,” Steve Turner at UKCEH said.

Drought was declared in England and Wales last summer, leading to hosepipe bans, farmers losing crops and some wildlife dying.

Rain in February was also in short supply in Wales and Northern Ireland, with Wales seeing just 22% of its average for the month.

This had caused water levels to fall in reservoirs and in groundwater, which supply drinking water to millions. In Wales reservoir levels were at their lowest for February since 1996.

River flows were below-average across much of the UK. The Trent in the Midlands, Erch in north Wales and Warleggan in Cornwall all broke their records for lowest water levels in February.

Low river flows are a serious threat to wildlife as they concentrate pollution, reduce oxygen levels and can affect fish breeding patterns, explains Joan Edwards, director of policy for The Wildlife Trusts.

“Last summer’s devastating droughts should be the wake-up call to protect the most precious of resources – water,” she said.

Dry weather also poses serious problems for farming.

In East Anglia, just 2.4mm rain fell on Andrew Blenkiron’s farm compared to the usual amount of around 50mm for February.

Low river levels meant he had little water to fill his reservoir. He has now been forced to cut back on plans to plant potatoes, onions, parsnips and carrots by around a fifth.

“We dare not plant a crop that requires irrigation,” he said.

His farm had barely recovered from the impacts of the intense heat last summer before the dry weather this year.

It is piling on the pressure in a year when energy prices have tripled his costs. He warns that if many farmers are forced to reduce their crops, it could affect food supplies in the autumn.

In the rest of Europe warnings are in place for dry conditions, including in France and Spain which could further affect supplies of tomatoes and salad.

Scientific analysis of the drought in Northern Europe in 2022 suggested that climate change made those dry conditions more likely.

Last month the chair of the National Drought Group, John Leyland, warned that England was just one dry spell away from drought this summer.

The chances of a dry spring are higher than normal, according to the Met Office three-month forecast.

The dry conditions in February highlighted “the need to remain vigilant” especially in areas that have not recovered from the drought last year, a spokesperson for Environment Agency said.

“We cannot rely on the weather alone, which is why the Environment Agency, water companies and our partners are taking action to ensure water resources are in the best possible position both for the summer and for future droughts,” they added.

Data visualisation by Erwan Rivault