Does a presidential candidate’s military service still matter to US voters?

The criticism came almost as soon as Tim Walz joined the Democratic presidential ticket: Did the Minnesota governor exaggerate his military record for political gain?

That was the line of attack Republicans zeroed in on. Just one day after Walz became the running mate of Democratic nominee Kamala Harris, Republicans were on the offensive, questioning his 24 years of National Guard service.

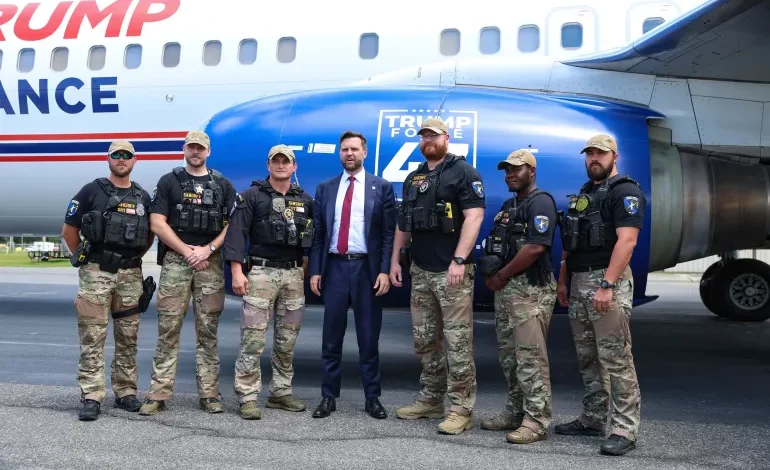

“I wonder, Tim Walz, when were you ever in war?” JD Vance, the Republican vice presidential pick, asked at a campaign stop on August 7. He proceeded to falsely accuse Walz of abandoning his unit on the eve of combat.

“What bothers me about Tim Walz is the stolen valour garbage. Do not pretend to be something that you’re not.”

But while Republicans continue to denounce Walz, experts say the importance of military service may be waning — at least, as far as rallying voters goes.

Wayne Lesperance, a political science professor and president of New England College, said the debate over Walz’s military record reminded him of how rare military experience has become in presidential races.

Not since 2008 and the George W Bush presidency has a military veteran served as an executive in the White House, either as a president or vice president.

“There was a time in American history where that sort of service — military service of any kind, really — was seen as something that was an absolute must,” Lesperance told Al Jazeera.

A fading tradition

In the current presidential race, neither of the two leading candidates has any military background whatsoever.

Harris, the Democrat, has spent nearly her entire career either as a prosecutor or in politics.

Her Republican adversary, former President Donald Trump, likewise avoided military service. He received several draft deferments during the Vietnam War and later established himself as a real estate tycoon and reality TV personality.

That marks a shift in United States tradition. Starting in the 1940s, the country was led by a string of veteran presidents. First there was Harry Truman, a colonel. Then Dwight Eisenhower, a general. Even Richard Nixon was a Navy Reserve commander.

But that streak ended in 1993, with the election of Democratic President Bill Clinton. In the three decades since, only one veteran, Bush, has reached the White House.

In the US, the president doubles as the head of the military, and Lesperance explained that previous generations of voters wanted their commander-in-chief to understand firsthand the stakes of sending young Americans to war.

“That was the big piece of it,” Lesperance said. “I think that sort of service was also a test of patriotism.”

A numbers game?

But a generational shift has taken place in the United States. Mandatory military service used to be a common facet of American life: During World War II, more than 10 million men were drafted into the military.

But the proportion of men drafted declined in subsequent conflicts. Over the course of the Vietnam War, for instance, only 1.86 million men were called to duty.

The draft ended in 1972, and military service has been voluntary ever since. As a result, the number of veterans in US society began to shrink further.

Today, the US military struggles to meet its recruiting goals. In the 2023 fiscal year, the Department of Defense reported that the military missed its target by 41,000 recruits.

Jeremy Teigen, an Air Force veteran and political science professor at Ramapo College of New Jersey, argues that the public has not lost interest in electing veterans. The problem is, fewer of them are available as candidates.

“The decline in military veterans [as candidates] is, in large part, explained by the fact that we stopped generating such huge pools of veterans,” Teigen said.

Lesperance echoed that observation. “What happened, it seems to me, is that there were fewer and fewer candidates that were emerging in the ’90s and beyond that had that military service,” he said.