Climate change: Warming could raise UK flood damage bill by 20%

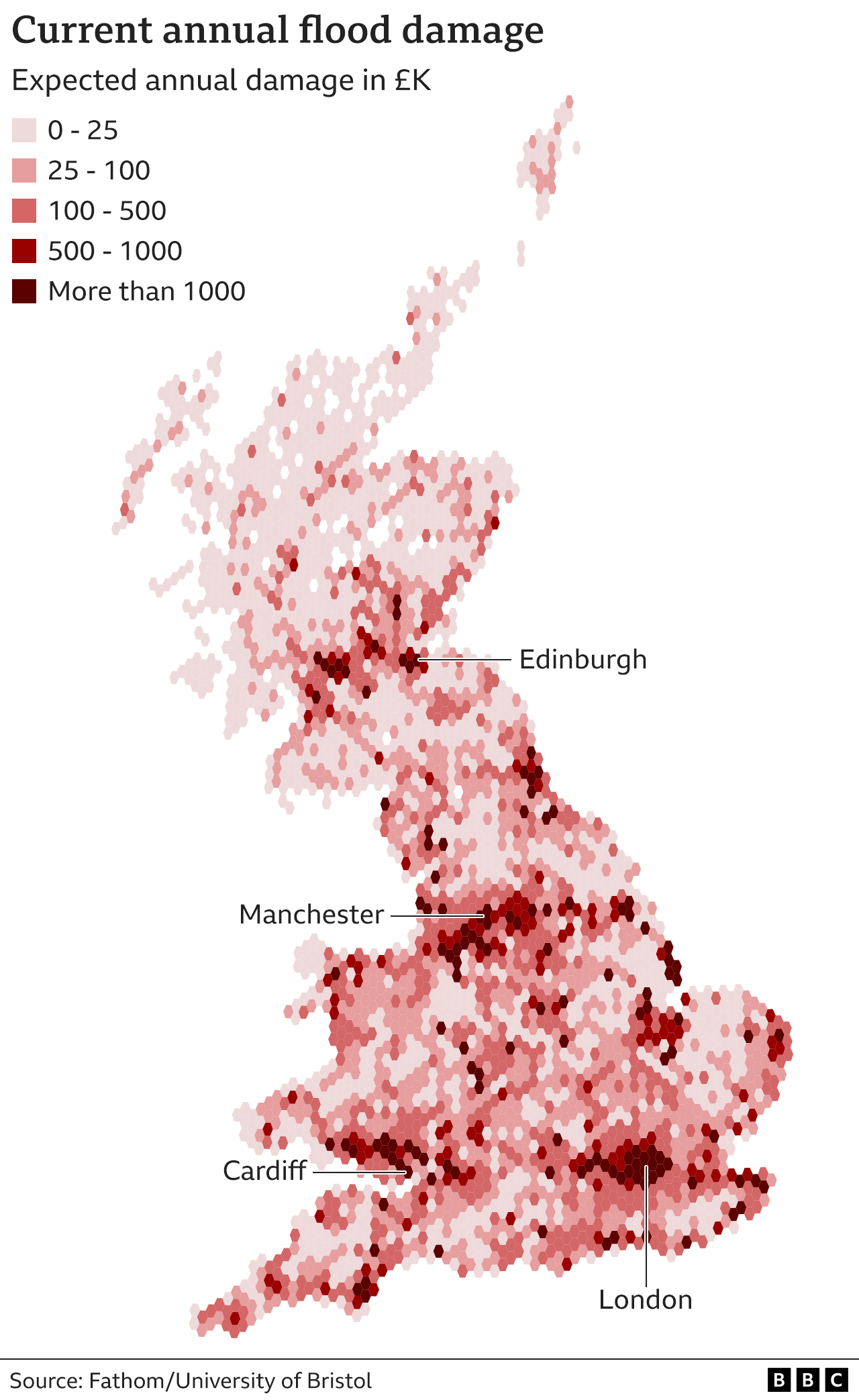

Researchers have produced a detailed “future flood map” of Britain – simulating the impact of flooding as climate change takes its toll.

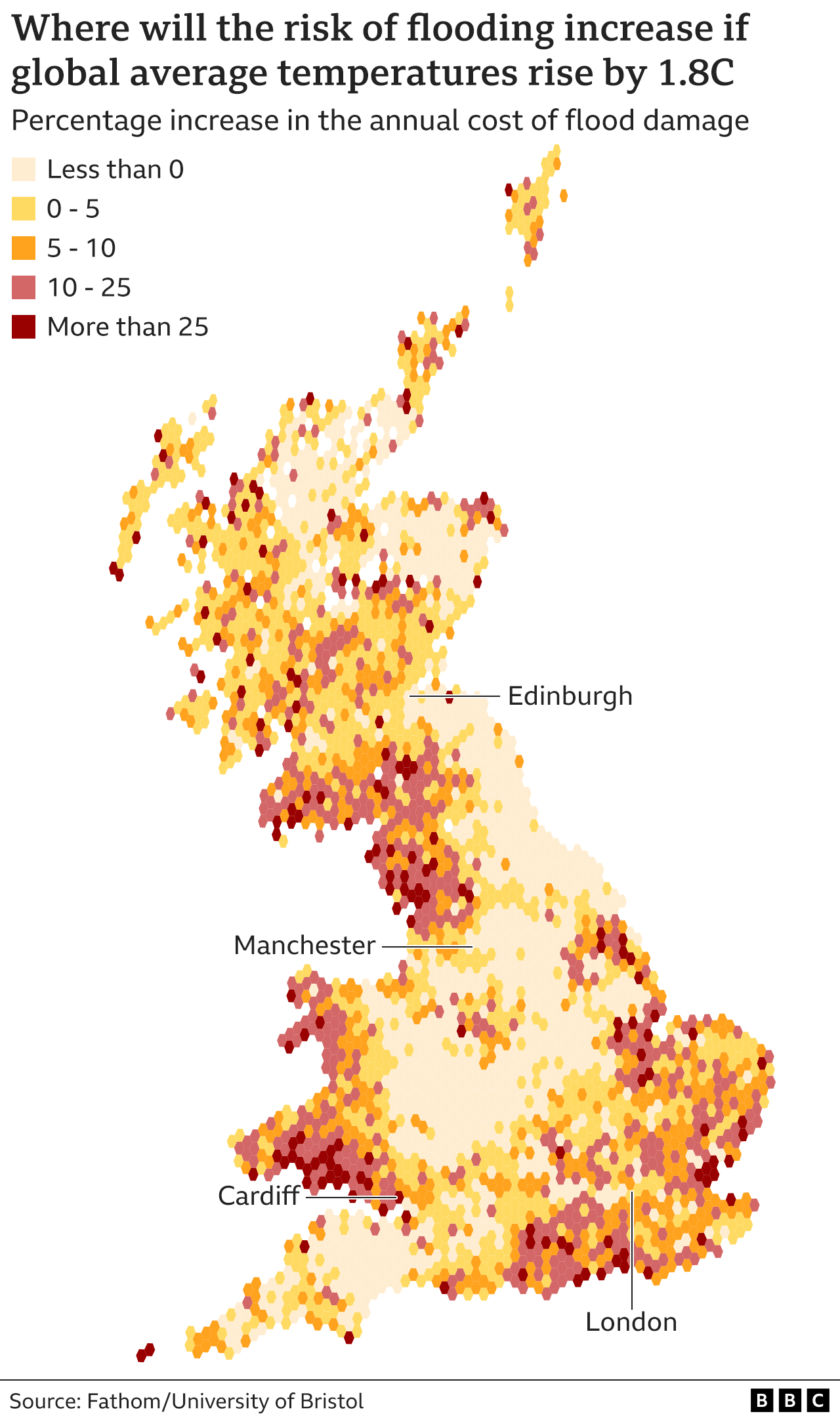

It has revealed that annual damage caused by flooding could increase by more than a fifth in today’s terms over the next century.

That could be reduced if pledges to reduce global carbon emissions are met.

Climate change is set to have a particular impact on “hotspots” where homes and businesses are in harm’s way.

Even if climate change pledges are met – keeping temperature increase to around 1.8C – places including south-east England, north-west England and south Wales are set to experience significantly increased flooding.

The detail in the new “flood risk map” also reveals locations that will be largely unaffected. This level of detail, the researchers say, is critical for planning decisions.

To create these flood risk maps, the research team from Bristol University and Fathom – a company that assesses flood and climate risk – simulated all types of flooding in the coming decades.

They used information about terrain, river flow, rainfall patterns and sea level to build a detailed picture of how much flood damage there would be to people’s homes and businesses across England, Scotland and Wales.

They combined this with Met Office climate predictions over the next century.

The team is also currently modelling flooding in Northern Ireland to expand the forecasts to include the whole of the UK as the climate warms.

The annual cost of flood damage across the UK currently, according to the Association of British Insurers, is £700m.

Chief research officer at Fathom, Dr Oliver Wing, explained that it was crucial to understand how that “flood risk landscape” would change in a warming world, because it will be different for every community.

“Our model shows that there are many places where flood risk is growing,” said Dr Wing. “Being able to understand the communities where this is likely to happen allows us to make sensible investment decisions – about flood defence structures, natural flood management or even moving people out of harm’s way.”

Calder Valley in West Yorkshire is one of the areas at particularly high risk from flooding caused by heavy rain.

Katie Kimber, from community volunteer group Slow the Flow, explained that the steep-sided valley meant that run-off swelled the river quickly.

“When it happens it’s really fast – it’s a wave of destruction,” she told BBC News. “Then it’s a case of clearing up the damage – it’s mentally and physically very hard for people here.”

During the 2015 Boxing Day floods, more than 3,000 properties were flooded in the Calder Valley, causing an estimated £150m of damage.

After the clean-up, Katie and other volunteers started their own flood-prevention efforts, with the help of the National Trust.

“We’re essentially creating speed bumps for the water running down the hillside [before it gets to the homes and businesses below],” she explained. “We’re stuffing the channels with branches.”

The community members also dig diversion channels to divert and slow water down.

Calderdale is a flood hotspot on the new map. But many places are set to see very little change or – when it comes to flood risk – actually improve, Dr Wing explained. Those areas include swathes of north-east and central England as well as eastern and northern Scotland.

This level of detail, according to the scientists, is missing from the government’s own current efforts to measure flood risk.

“Current government flood maps are not scrutinised by scientists, generally speaking,” said Dr Wing. “The methods they use are not transparent.

“And every pound we spend on flood risk mitigation is a pound that could be spent on teachers, nurses, hospitals, schools, so it’s really important that it’s grounded in accurate science.”

The scientists add that the UK as a whole is “not well adapted to the flood risks it currently faces, let alone any further increases in risk due to climate change”. They hope this detailed forecast could help change that.

Back on the Calderdale hillside, Katie says that better forecasting would be invaluable.

“Anything that helps us to prepare and plan,” she said. “Because we want to keep living here – we love this area. So we need to face these challenges, particularly with climate change.”

Dr Wing added that the new, detailed maps could help land use planning decisions.

“Those are something that ultimately put people in the way of floods in the first place,” he said. “That’s something we see the world over – that the most important part of flood risk is where people are, not necessarily how the floods are changing.”