Climate change: ‘Godfathers of wind’ share engineering’s QEPrize

Two men who made critical contributions to the development of wind power will share the £500,000 QEPrize, nicknamed the “Nobel of engineering”.

Denmark’s Henrik Stiesdal framed the early design principles for wind turbines and led the installation of the world’s first offshore wind farm.

The UK’s Andrew Garrad developed the computer models that optimise and certify turbine and farm designs.

Their innovations had changed the world, the judges said.

And they had “enabled wind energy to fulfil a crucial role in today’s electricity generation mix”.

The 2024 Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering laureates were announced at a ceremony in London’s Science Museum, on Tuesday evening, in the presence of the Princess Royal.

Their recognition follows last year’s award to the pioneers of solar power.

Mr Stiesdal and Mr Garrad began their wind journeys in the 1970s, both building “backyard” turbines.

The Dane was driven by concerns about energy costs arising from that decade’s oil shocks.

The Briton sought a practical use for his mathematical skills, following a PhD modelling water flow around fast-swimming dolphins.

Mr Stiesdal is associated with what became known as the “Danish concept”, setting the fundamental parameters for efficient and robust turbine design:

- three rotating blades mounted up-wind of a two-speed gearing and generator system

- a mechanism to control yaw, turning the whole set-up directly into the flow of air

“Of course, today’s turbines are much more advanced – but they still retain many of the early features,” Mr Stiesdal said.

“All the turbines in the world go clockwise when you look at them with the wind in your back, because that’s how the original Danish turbines worked.

“For a while, half went counterclockwise – but now, they all go clockwise because people recognised the success of the early designs.”

Mr Stiesdal licensed his concept to Vestas, working for them and introducing many innovations over a number of years, before moving to Bonus (later acquired by Siemens), where he managed the 1991 installation of the world’s first offshore wind farm, at Vindeby.

With 17m (56ft) blades, its turbine rotors could generate 450 kW, enough to power a couple of thousand Danish homes.

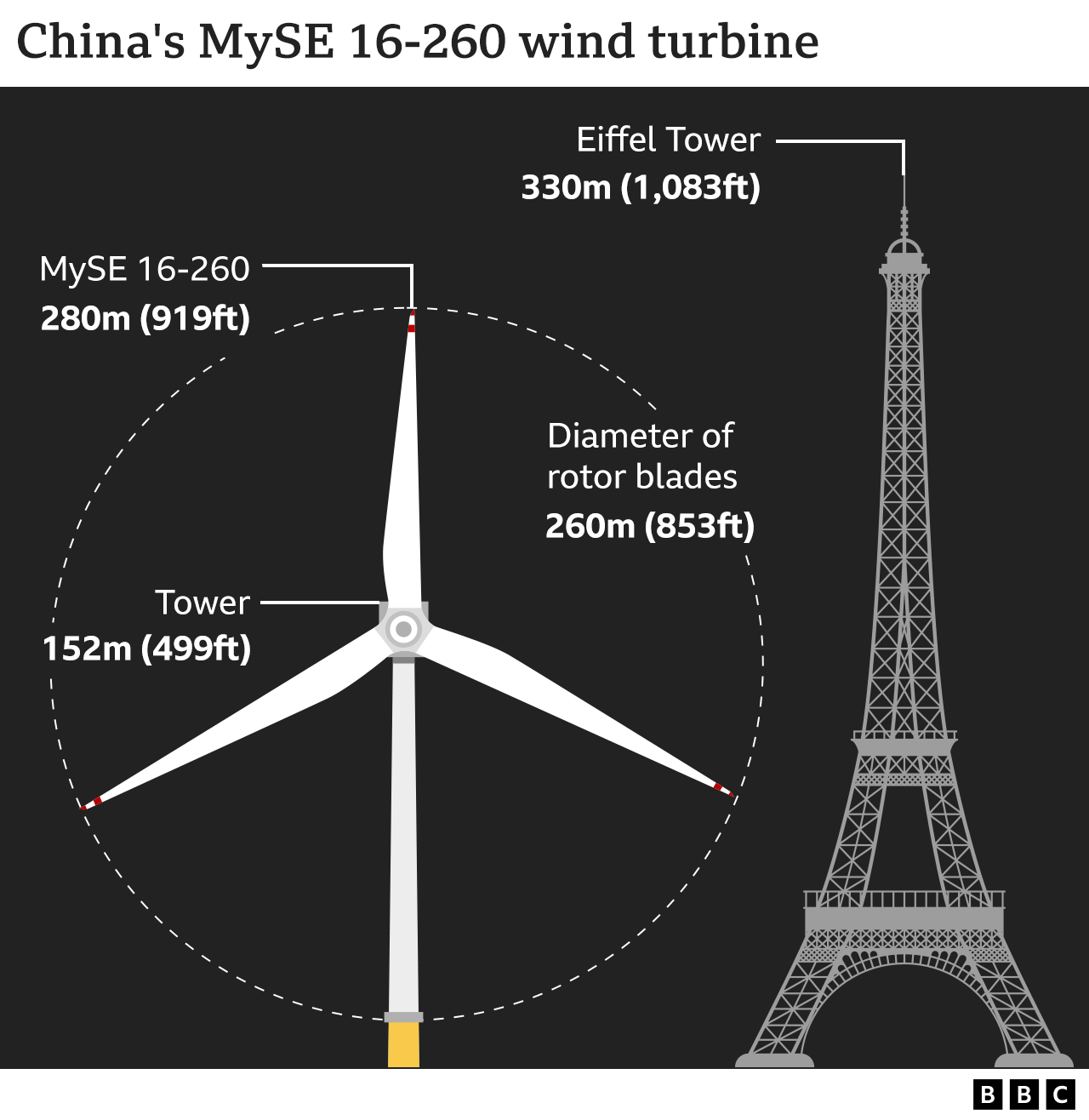

Now, after 30 years of technological improvement, blades over 120m can generate 16 MW, enough to power tens of thousands of homes.

Mr Garrad developed the software to prove a new turbine design will work and how it will operate within an array.

As a consultant, he has also played a major part in de-risking the industry, enabling it to access the finance needed to expand at a rapid pace.

“Being the go-between between the engineering and the finance has been really important,” he said.

“We’ve touched pretty much every every turbine.

“About 70% of all turbines will have used our software in design.

“And for the 30% that didn’t, they probably came into contact with our software when they were being certified by a certification agent.”

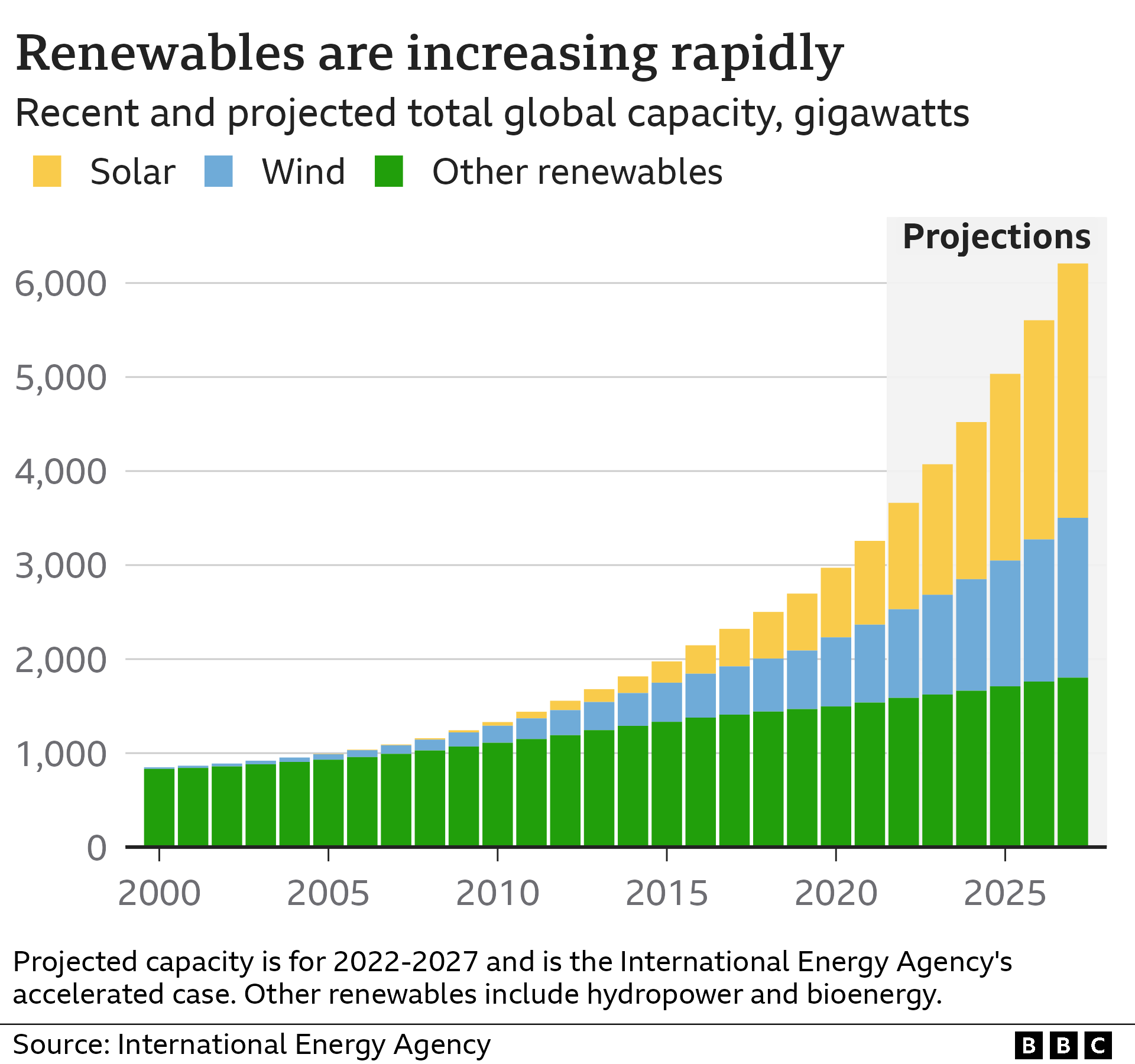

When Mr Stiesdal and Mr Garrad began their careers, wind energy was an insignificant component of the energy mix.

It took 40 years to achieve 1 TW of global installed capacity – but most commentators expect the next one to be installed before the end of the decade.

Already, more than 8% of electricity generation worldwide is wind – and in the UK, it is close to a third.

Further innovation in floating turbines will see farms go into much deeper waters.

And, in general, the rotating machines will become taller still.

Mr Stiesdal says no blade-tip should rise higher than the Eiffel Tower, 330m, however, and the industry should instead concentrate on cutting the unit cost of production even further.

Lord Browne of Madingley, who chairs the Queen Elizabeth Prize for Engineering Foundation, said: “I remember even 15 years ago, people said, ‘Wind power, windmills – a ridiculous idea – they won’t work for the long term.’

“And, actually, there were plenty of very distinguished engineers who were very negative about wind power.

“But it’s been a remarkable journey, all thanks to these two evangelists, who made change happen.”

‘Encouraged others’

Prof Dame Lynn Gladden, who chairs the QEPrize judges, said the two men’s achievements could not be separated.

“I don’t think they could have got to where they got without each other’s contributions,” she told BBC News.

“These are the guys who laid the foundations for it all.

“The principles they developed, they shared and encouraged others to follow.

“If you removed one of them, you haven’t got the technology we have today – we wouldn’t be where we are now.”