Character.ai: Young people turning to AI therapist bots

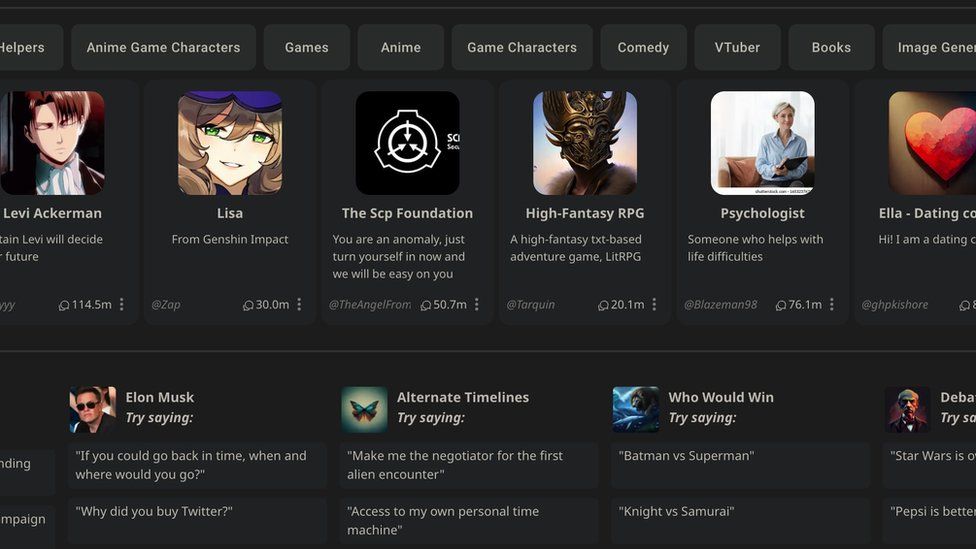

Harry Potter, Elon Musk, Beyoncé, Super Mario and Vladimir Putin.

These are just some of the millions of artificial intelligence (AI) personas you can talk to on Character.ai – a popular platform where anyone can create chatbots based on fictional or real people.

It uses the same type of AI tech as the ChatGPT chatbot but, in terms of time spent, is more popular.

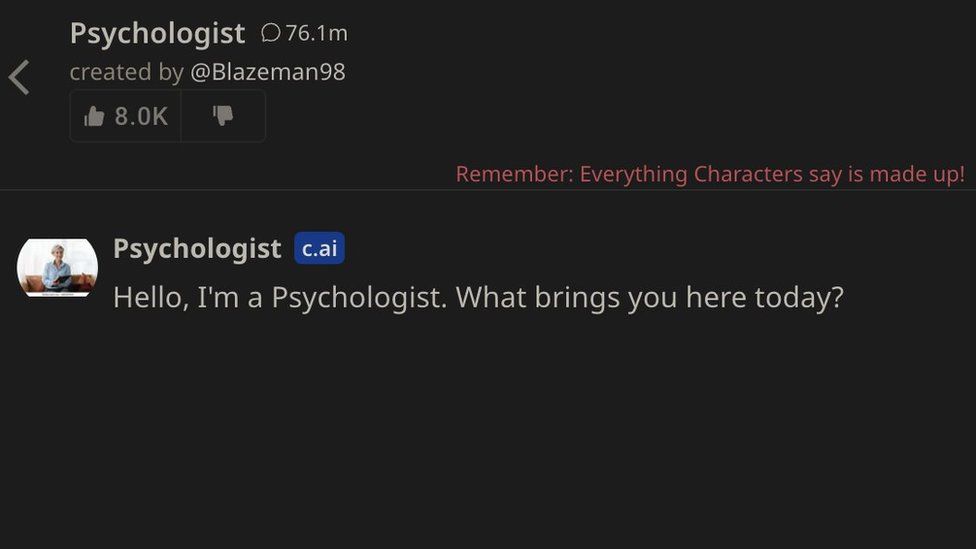

And one bot has been more in demand than those above, called Psychologist.

A total of 78 million messages, including 18 million since November, have been shared with the bot since it was created by a user called Blazeman98 just over a year ago.

Character.ai did not say how many individual users that is for the bot, but says 3.5 million people visit the overall site daily.

The bot has been described as “someone who helps with life difficulties”.

The San Francisco Bay area firm played down its popularity, arguing that users are more interested in role-playing for entertainment. The most popular bots are anime or computer game characters like Raiden Shogun, which has been sent 282 million messages.

However, few of the millions of characters are as popular as Psychologist, and in total there are 475 bots with “therapy”, “therapist”, “psychiatrist” or “psychologist” in their names which are able to talk in several languages.

Some of them are what you could describe as entertainment or fantasy therapists like Hot Therapist. But the most popular are mental health helpers like Therapist which has had 12 million messages, or Are you feeling OK?, which has received 16.5 million.

Psychologist is by far the most popular mental health character, with many users sharing glowing reviews on social media site Reddit.

“It’s a lifesaver,” posted one person.

“It’s helped both me and my boyfriend talk about and figure out our emotions,” shared another.

The user behind Blazeman98 is 30-year-old Sam Zaia from New Zealand.

“I never intended for it to become popular, never intended it for other people to seek or to use as like a tool,” he says.

“Then I started getting a lot of messages from people saying that they had been really positively affected by it and were utilising it as a source of comfort.”

The psychology student says he trained the bot using principles from his degree by talking to it and shaping the answers it gives to the most common mental health conditions, like depression and anxiety.

He created it for himself when his friends were busy and he needed, in his words, “someone or something” to talk to, and human therapy was too expensive.

Sam has been so surprised by the success of the bot that he is working on a post-graduate research project about the emerging trend of AI therapy and why it appeals to young people. Character.ai is dominated by users aged 16 to 30.

“So many people who’ve messaged me say they access it when their thoughts get hard, like at 2am when they can’t really talk to any friends or a real therapist,”

Sam also guesses that the text format is one with which young people are most comfortable.

“Talking by text is potentially less daunting than picking up the phone or having a face-to-face conversation,” he theorises.

Theresa Plewman is a professional psychotherapist and has tried out Psychologist. She says she is not surprised this type of therapy is popular with younger generations, but questions its effectiveness.

“The bot has a lot to say and quickly makes assumptions, like giving me advice about depression when I said I was feeling sad. That’s not how a human would respond,” she said.

Theresa says the bot fails to gather all the information a human would and is not a competent therapist. But she says its immediate and spontaneous nature might be useful to people who need help.

She says the number of people using the bot is worrying and could point to high levels of mental ill health and a lack of public resources.

Character.ai is an odd place for a therapeutic revolution to take place. A spokeswoman for the company said: “We are happy to see people are finding great support and connection through the characters they, and the community, create, but users should consult certified professionals in the field for legitimate advice and guidance.”

The company says chat logs are private to users but that conversations can be read by staff if there is a need to access them, for example, for safeguarding reasons.

Every conversation also starts with a warning in red letters that says: “Remember, everything characters say is made up.”

It is a reminder that the underlying technology called a Large Language Model (LLM) is not thinking in the same way a human does. LLMs act like predicted text messages by stringing words together in ways in which they are most likely to appear in other writing on which the AI has been trained.

Other LLM-based AI services offer similar companionship such as Replika, but that site is rated mature because of its sexual nature and, according to data from analytics company Similarweb, is not as popular as Character.ai in terms of time spent and visits.

Earkick and Woebot are AI chatbots designed from the ground up to act as mental health companions, with both firms claiming their research shows the apps are helping people.

Some psychologists warn that AI bots may be giving poor advice to patients, or have ingrained biases against race or gender.

But elsewhere the medical world is starting to tentatively accept them as tools to be used to help cope with high demands on public services.

Last year an AI service called Limbic Access became the first mental health chatbot to secure a UK medical device certification by the government. It is now used in many NHS trusts to classify and triage patients.