Biden’s Ukraine disaster was decades in the making

Leonid Ragozin

President Joe Biden is about to wrap up what many perceive as a disastrous presidency. His departure from the White House could potentially mark a turning point in both the Russia-Ukraine conflict and in the three decades of poorly thought-out Western policies which resulted in the alienation of Russia and the collapse of its democratic project. But that hinges on the incoming President Donald Trump’s ability not to repeat the mistakes of his predecessors.

It is Russian President Vladimir Putin who decided to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, but the ground for this conflict was prepared by US securocrats in the 1990s. Back then, Russia had just emerged from the dissolution of the USSR much weaker and disoriented, while the Russian leadership, idealistic and inept as it was at the time, worked on the assumption that full-blown integration with the West was inevitable.

The problem was never the eastward expansion of NATO – a security pact created to confront the Soviet Union – and the European Union per se, but Russia’s exclusion from this process.

Crucially, this approach set Ukraine on the course of Euro-Atlantic integration while Russia was kept out of it – creating a rift between two nations closely linked to each other by history, economic and interpersonal relations. It also precipitated Russia’s securitisation and backsliding on democracy under Putin.

This outcome was never pre-destined and it took relentless efforts by American securocrats to bring it about.

One of the lost chances for a different path was the Partnership for Peace programme, officially launched by the Clinton administration in 1994. It was designed to balance the desire of former Warsaw Pact countries to join NATO and the crucial goal of keeping Russia on board – as a major nuclear power and a new democracy with a clearly pro-Western government.

Russia joined it but, as the American historian Mary Sarotte writes in her book Not One Inch, this useful framework was derailed at its inception by a small number of securocrats in Washington.

She specifically talks about “the pro-expansion troika”, consisting of Daniel Fried, Alexander Vershbow, and Richard Holbrooke, who pushed for an aggressive expansion of NATO, disregarding protests from Moscow.

Sarotte also mentions John Herbst as the author of a later report on unofficial promises of NATO’s non-expansion made to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev which, as she suggests, shaped the US policy of ignoring Russia’s complaints about NATO expanding all the way to its borders for decades to come.

The unreflective arrogance and triumphalism that these securocrats embody can also be seen in Biden himself who back then was a prominent member of Congress. In a 1997 video, he mocked Moscow’s protests against NATO expansion by saying that Russia would have to embrace China and Iran if it kept being intransigent. He clearly assumed it to be an absurd and unrealistic scenario back then – believing, perhaps, that Russia had no choice but to stay in the Western orbit. But it turned out exactly along the lines of what he thought was a smart joke.

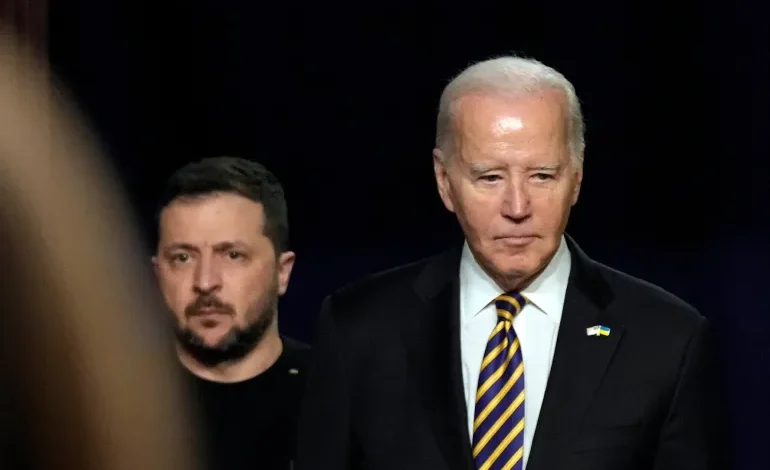

In his hawkish politics on Russia, Biden found a willing partner in the Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy. It is hardly a coincidence that Zelenskyy’s massive U-turn on relations with Russia started as Biden took office.

The Ukrainian president had been elected on the promise that he would end the simmering conflict that began with the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. He met with Putin in Paris in December 2019 and the two agreed to a ceasefire in the Donbas region, which both sides had largely respected, reducing the number of deaths to near zero.

But once Biden set foot in the White House, Zelenskyy ordered a clampdown on Putin’s Ukrainian ally Viktor Medvedchuk, while simultaneously launching loud campaigns for Ukraine’s NATO membership, the return of Crimea, as well as for the derailing of the Russo-German Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline project.

Two factors may have played into Zelenskyy’s decisions. Azerbaijan’s victory over Russian-backed Armenian forces in the fall of 2020, achieved largely thanks to Turkish Bayraktar drones, gave hopes that high-tech warfare against Russia could be successful. The other factor was that in December 2020, polls showed Medvedchuk’s party ahead of Zelenskyy’s.