Bangladesh’s latest election battlegrounds: TikTok, Facebook, YouTube

The fast-paced, rhythm-driven song’s lyrics could come across as commentary about life in rural Bangladesh.

“The days of boat, the sheaf of paddy and the plough have ended; the scales will now build Bangladesh”, the words go.

In reality, though, the song is a political anthem supportive of Bangladesh’s Jamaat-e-Islami party that went viral on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram and TikTok in early November.

It speaks of the symbols of parties that have governed Bangladesh that it argues Bangladeshis now want to reject: The boat is the symbol of the Awami League (AL) of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, who was ousted by a student-led uprising in August 2024; the sheaf of paddy is the symbol of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP); and the plough, the election symbol of the Jatiya Party, a former ally of Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League, founded by a military ruler in the 1980s.

The Jamaat’s symbol is scales.

On February 12, the country is scheduled to vote in what is shaping up to be a direct contest between the BNP and a Jamaat-led alliance. On-the-ground campaigning starts on Thursday, January 22. But online, parties have been battling it out for months, trying to attract Gen Z voters who played a key role in overthrowing Hasina, and now could play a pivotal role in determining who forms the next government.

The pro-Jamaat song’s online popularity, for instance, sparked a frenzied race among parties to launch songs in an election climate when mass rallies are no longer the only way to reach millions of voters: Social media is often as powerful a tool.

HAL Banna, a London-based filmmaker who composed and sang the pro-Jamaat song, told Al Jazeera it was initially produced for a single candidate in Dhaka. “When people started sharing it, other candidates realised it connected with ordinary voters and began using it,” he said.

The BNP came up with its campaign song, its lyrics suggesting that the party – only marginally ahead of the Jamaat in opinion polls – puts the country before itself. “Amar agey amra, amader agey desh; khomotar agey jonota, shobar agey Bangladesh [Us before ourselves, the country before us; people before power, Bangladesh above all],” the song says.

The National Citizen Party, formed by students at the forefront of the anti-Hasina protests in 2024, also came up with its song that went viral.

But music has been only one part of a wider digital push.

Short, dramatised videos, emotional voter interviews, policy explainers and satire have also flooded social media.

This year, the online war is bigger than a parliamentary contest alone.

On February 12, voters will also decide on a referendum on the July National Charter, a reform package the interim government led by Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus says must be endorsed to institutionalise changes in the state institutions introduced after the 2024 July uprising.

Why online matters

According to the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission, Bangladesh had about 130 million internet users as of November 2025, accounting for roughly 74 percent of its estimated 176 million population.

According to a report released in late 2025 by DataReportal, a global digital research and analytics platform report, the country has approximately 64 million Facebook users, nearly 50 million YouTube users, 9.15 million Instagram users and more than 56 million TikTok users aged 18 and above. X, by contrast, has a relatively small footprint with about 1.79 million users.

That digital reach, say analysts, helps explain why political parties are investing heavily in online narratives.

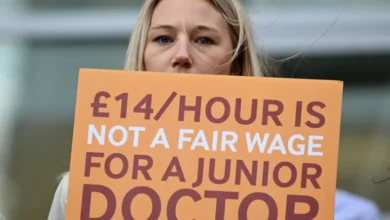

Election Commission data show that 43.56 percent of voters are aged between 18 and 37, many of them first-time voters or young Bangladeshis who effectively felt disenfranchised under Hasina. National elections in 2013, 2018 and 2024 were marred with irregularities, crackdowns on opposition leaders and activists, and boycotts that turned them into sham votes. That experience has turned frustration into determination to participate in the upcoming vote, say analysts.Digital strategies

Bangladeshi authorities have banned the Awami League from political activities, including participation in the February elections.

That has turned the elections into a bipolar competition.

On one side is a BNP-led alliance, which presents itself as the experienced governing alternative to the Awami League’s excesses – Hasina’s government was accused of mass killings, forced disappearances and corruption. The BNP ruled Bangladesh between 1991 and 1996, and then again between 2001 and 2006.

On the other side is a Jamaat-led alliance, which includes the NCP.

Mahdi Amin, a BNP leader, told Al Jazeera that the party is focusing on distributing policy proposals and collecting voter feedback. “BNP remains a political party with a track record of governing the country. We have specific plans in every sector,” he said.

To drive online engagement, the BNP has launched websites such as MatchMyPolicy.com, where voters can register agreement or disagreement with policy proposals the party says it would implement if elected.

Like the BNP, the Jamaat-e-Islami has also launched a website – janatarishtehar.org – that it has said is aimed in part at seeking the opinion of voters to prepare the party’s election manifesto.

Jubaer Ahmed, a Jamaat leader, said that the party’s online efforts were focused on sharing “the narratives we believe in”. Asked about other parties and their efforts, Ahmed said: “We observe others, but we don’t follow. Our competition will be intellectual.”

Is anyone winning the online battle?

Analysts caution against declaring a clear victor.

Mubashar Hasan, an adjunct fellow at Western Sydney University’s Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative, pointed to apparently different areas of focus in the two campaigns’ strategies.

Hasan said BNP’s online content often packages its key pledges into short, captioned videos and shareable cards. For instance, some posts promote a proposed “Family Card” scheme under which 5 million women and households would receive 2,000–2,500 taka ($16-20) a month or essential goods if the BNP is elected. Other clips and graphics talk of a “Farmer Card” plan, promising fair prices for fertilisers, seeds and pesticides, plus incentives, easier loans and insurance coverage for farmers.

On the other hand, he argued, pro-Jamaat online content often focuses on attacking the BNP as “no different” to the Awami League.

Qadaruddin Shishir, editor of the fact-check outlet The Dissent, said that Jamaat-aligned online campaigns also seek to tap into anti-India messaging: Hasina is in exile in India after fleeing in August 2024, and New Delhi has refused to send her back despite multiple requests from Dhaka.

“These themes increasingly circulate beyond Jamaat’s base, including among young users, through memes and copied formats,” he said.

Referendum goes viral, too

This year, the online battle is not limited to party-versus-party competition. It also centres on a state-backed referendum on a set of broad-based reforms outlined in what has come to be known as the July Charter – named after the uprising that led to Hasina’s removal.

Bangladesh’s interim government has launched a digital campaign in favour of a ‘Yes’ vote, using official websites and social media platforms. Interim leader Yunus’s Press Secretary Shafiqul Alam told Al Jazeera the strategy reflects a media landscape where traditional outlets have steadily lost reach.

“Legacy media is being used less and less,” Alam said, adding that online campaigning was necessary to secure public approval to institutionalise the reforms.

The charter proposes limits on prime ministerial power, stronger checks on security forces, and safeguards to prevent election manipulation. It also calls for judicial independence and constitutional reforms aimed at stopping the return of authoritarian rule.

The NCP, which emerged from the July uprising, has also campaigned online for a ‘Yes’ vote in the referendum.

To be sure, said analysts and content creators, offline campaigning remains critical. HAL Banna, composer of the pro-Jamaat song that set off the trend of viral campaign songs online this election season, said physical campaigning still has no match when it comes to “reach and impact”.

But, he said, “online campaigns set discussion topics among people offline”. With an electorate as young as Bangladesh’s, that can be the difference between winning and losing.