Attenborough ship encounters mammoth iceberg

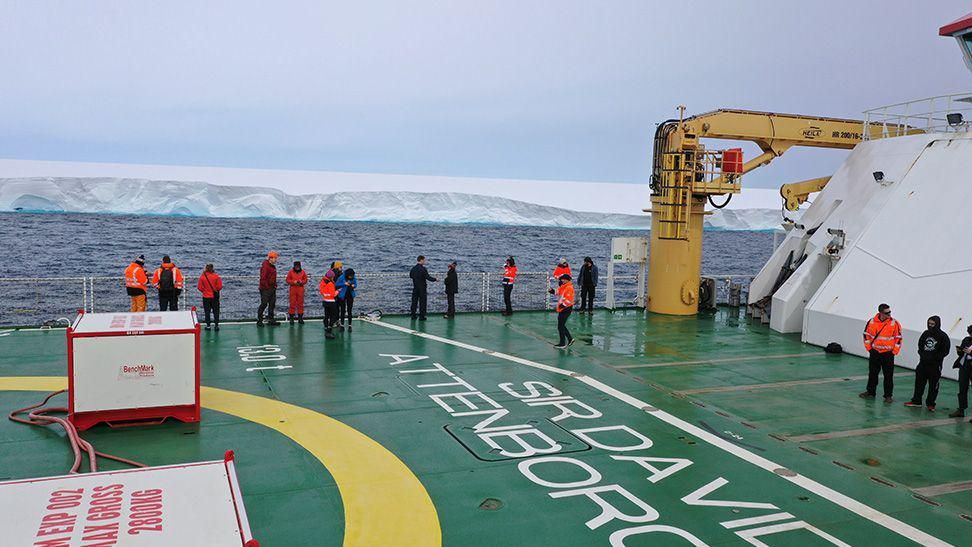

The UK’s polar ship, RRS Sir David Attenborough, has come face to face with the world’s biggest iceberg.

The planned encounter allowed scientists on board the research vessel a closer look at one of the true wonders of the natural world.

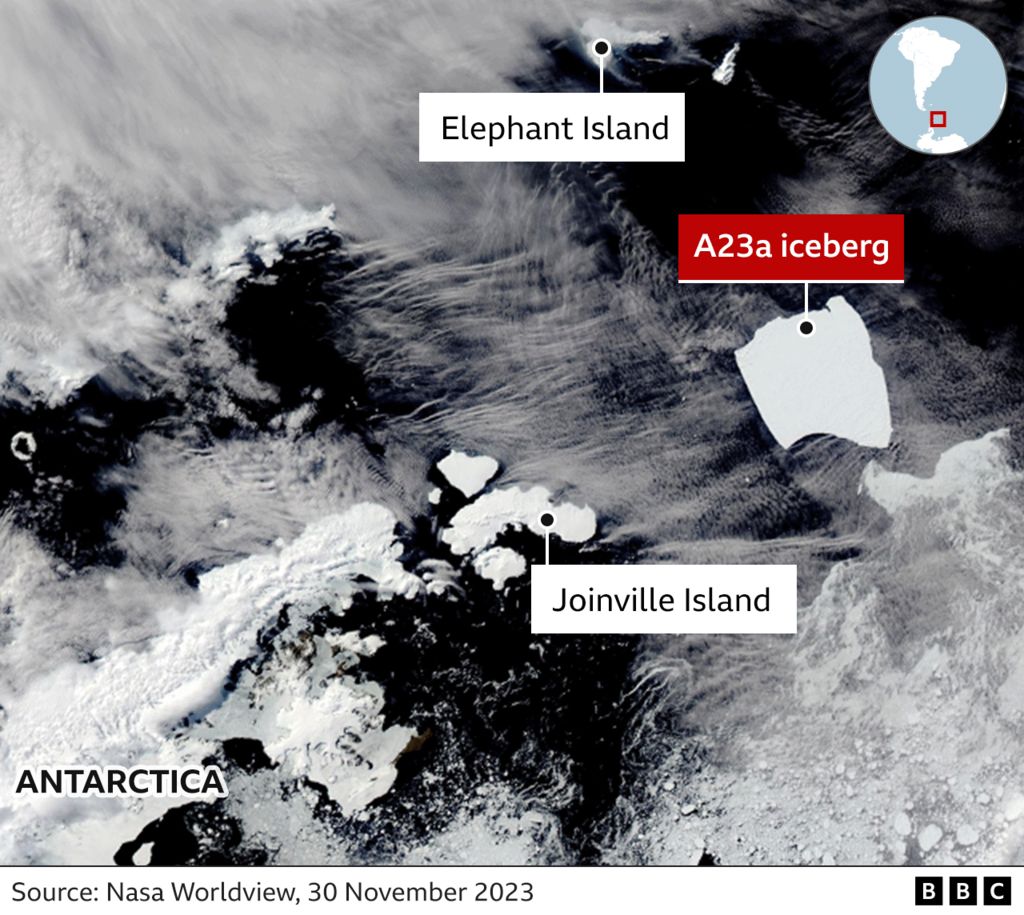

A23a, as the berg is known, covers 3,900 sq km (1,500 sq miles), twice the size of Greater London.

It broke from the Antarctic coast in 1986 and has spent much of the time since stuck fast to the seafloor.

But during the past year, currents and winds have driven the frozen block rapidly across the Weddell Sea. And it is now set to spill beyond the White Continent, into the Southern Ocean.

The Attenborough intercepted A23a on Friday, 1 December, about 90km (56 miles) north-east of Joinville Island, at the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

It was a fortuitous meeting. The ship was on its way to Signy Island and the behemoth in its path.

A drone was put up to fly over the berg’s immense cliffs. But it remains difficult to appreciate its mammoth scale.

The white of A23a’s surface extends to the horizon. But most of the berg’s bulk is below the waterline.

Some sections may be more than 300m (1,000ft) thick.

And even travelling at 10 knots (19km/h), it took the Attenborough several hours to sail along two sides of the square berg.

As it moves north into warmer waters, A23a will melt and fragment

The £200m research ship is on its first full scientific mission to the White Continent after completing all its trials.

Its activity in the Weddell Sea will inform the British Antarctic Survey’s Biopole project, studying how polar regions cycle carbon and nutrients to keep the oceans healthy, with an emphasis on the consequences for climate change.

In this respect, A23a is a very useful subject for observation.

As these big bergs melt, they release the mineral dust incorporated into their ice when they were part of glaciers scraping along the rock bed of Antarctica.

This dust is a source of nutrients for the organisms such as phytoplankton that form the base of ocean food chains.

And the Attenborough took the opportunity on Friday to collect water samples around A23a.

The above-water ice cliff is tens of metres high

“These icebergs provide different sources of nutrients,” explained Prof Geraint Tarling, Biopole’s principal investigator.

“As you say, there’s the rock they’ve scraped; there’s the dust that’s collected on their surface over many years; and they also capture and store nutrients. All of this they can dump in the ocean and have quite prolific effects on productivity over quite a small area, and that can act as a huge sponge to take carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” he said.

An orca surfaces just in front of the iceberg

A23a has moved about 1,500km from where it spent more than three decades pinned to the seafloor.

Like most icebergs from the Weddell sector, it is almost certain now to be ejected into the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which will throw it on to a path known as “iceberg alley”.

And this may well take it towards the British overseas territory of South Georgia.

Satellite images from the weekend show another giant ice block, “Molar Berg”, or D28, already drifting next to the remote island.

Molar Berg and A23a had a near collision, far south in the Weddell Sea, in June 2022.

It took the Attenborough several hours to sail two sides of the berg