Atomic grains of sand: How the history of humans is written into the fabric of the Earth

Moments in human history are etched into the Earth. Now researchers are piecing together evidence of our impact on the planet – through the marks we’ve left on nature.

The microbes living in this French harbour have never recovered from World War Two. Between 2012 and 2017, Raffaele Siano pulled sediment cores from the seabed at Brest harbour, wondering what he was going to find. When he and his colleagues at the French Institute for Ocean Science (Ifremer), analysed the fragments of DNA captured in those cores – they discovered something remarkable.

The oldest, deepest layers of sediment – dating to before 1941 – had traces of plankton called dinoflagellates that were strikingly different to the genetic traces of plankton left in the shallower, more recent layers. “There was a group, an order of these dinoflagellates, that was very abundant before World War Two – and after World War Two it almost disappeared,” says Siano. He and his colleagues published a study detailing their findings in 2021.

Siano mentions that Brest harbour had been bombed during the war. Then, in 1947, a Norwegian cargo ship exploded in the Bay of Brest. The disaster killed 22 people and spread ammonium nitrate, a toxic chemical used to make fertiliser and explosives, into the sea. Even younger sediment in the 1980s and 1990s showed further changes in the plankton community in the harbour. “We correlated this from another type of pollution coming from intensive agricultural activities,” says Siano.

Nature has a way of remembering things. Echoes of certain human activities, especially highly-polluting ones, sometimes show up in tree rings, coastal sediments and ecosystems. Arguably, these traces are hints of the Anthropocene, a proposed geological epoch in which humanity is said to have irrevocably, and drastically, altered Earth. Human history, it turns out, is written into the very fabric of our planet – and the life that co-exists here with us.

Siano and his colleagues are predominantly ecologists but they also work with historians. “The land changed because of human impact and also because of historical events,” Siano says. When the team analysed the sediment cores from Brest, they also detected a gradual rise in heavy metal pollution as time passed. Younger layers of sediment contained higher volumes of mercury, copper, lead and zinc, for example.

The report notes there were similar levels of some of these metals – especially lead and chromium – in Pearl Harbour, a major US naval base in Hawaii that was heavily bombed by Japanese warplanes in 1941. However, Siano adds that he can’t be sure whether these metals came directly from the bombs themselves. Either way, there is a signal in both Brest and Pearl Harbour of a calamitous, and polluting, moment in human history.

Other researchers have also scoured the planet in search of geological records of anthropogenic pollution. In China, soil sediments reveal a sharp increase in metal contamination since 1950 – which correlates with a rise in air pollution there during the second half of the 20th Century. A separate study explores how the emergence of industries such as shipbuilding may be linked with a higher incidence of heavy metal deposits in tree rings from certain parts of China.

Even Roman metallurgy, from many centuries ago, has left its mark. One 2022 study found a noticeable rise in lead contamination in ice, sediment and peat cores from Europe, correlated with the development of Roman industry. It is sometimes difficult to be sure which specific events caused spikes in lead contamination, however, note the authors.

The bomb turned buildings into dust… and spread this material across the nearby landscape – marking it forever

Jean-Luc Loizeau at the University of Geneva has studied the sediment of Lake Geneva, particularly the material found in a small area of the lake near to a wastewater treatment plant. He says the sediment there contains many traces of human activities. Crucially, the way water moves around in this part of the lake has helped to preserve such clues.

“It accumulates because there is a kind of gyre that keeps the sediment within the bay,” he says, referring to Vidy Bay, on the northern shores of the lake. In a 2017 paper, he and colleagues describe the heavy metal pollution that became evident here in sediment layers dating to the 1930s. Among the specific examples he gives is a spike in mercury contamination during the 1970s.

“We know there was an accident in one of these industries,” explains Loizeau. “There was some spilling of mercury because there was a break in a tank and we really find this peak in the sediment.” Plus, traces of elements such as barium in the cores could be linked to the rise of the automobile, adds Loizeau – because car brakes often contain barium.

Besides metals, radioactive materials have also found applications in various industries. In Switzerland, for instance, radium was long used to make glow-in-the-dark details on watch faces. Remnants of radium from the watchmaking industry have turned up in landfill sites and buildings in the country.

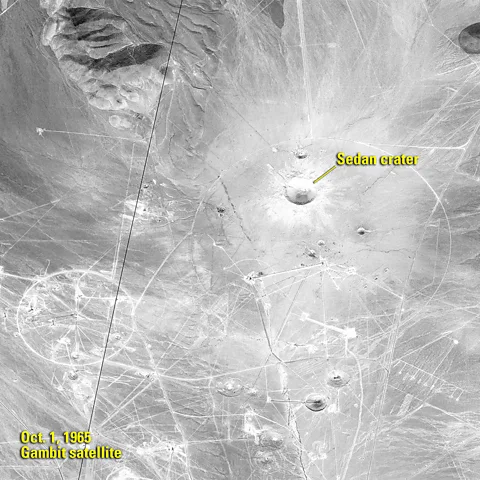

And scattered around the globe are pieces of evidence that reveal the grim legacy left by nuclear weapons during the 20th Century. Take the giant craters in the Nevada desert made by huge weapons tests, for example. But some contamination caused by nuclear detonations is much more subtle.

In 2019, researchers revealed that some of the grains of sand on beaches near the Japanese city of Hiroshima are in fact particles of debris created when the US dropped an atomic bomb on the city on 6 August 1945, towards the end of World War Two. “The chemical composition of the melt debris provides clues to their origin, particularly with regard to city building materials,” the authors wrote. In other words, the bomb turned buildings into dust, heat from the explosion reshaped that dust, and the blast ultimately spread this material across the nearby landscape – marking it forever.