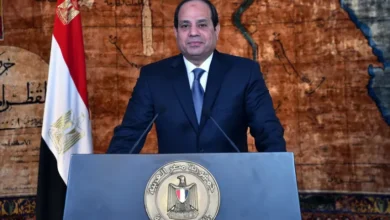

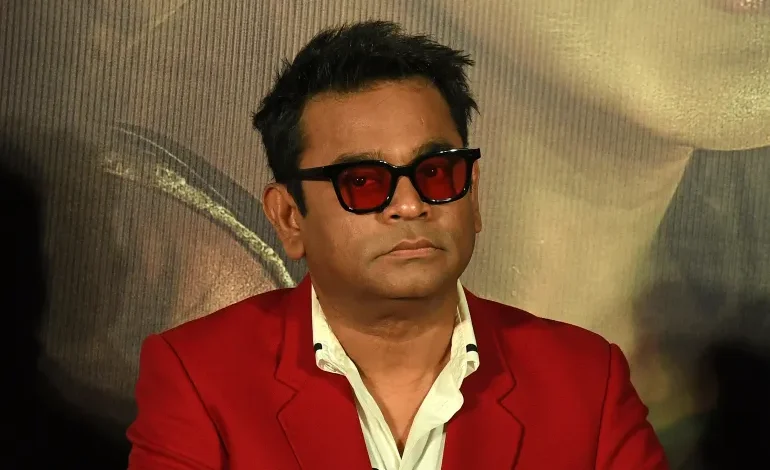

AR Rahman: Indian composer faces backlash for ‘bias’ in Bollywood remarks

Allah Rakha Rahman, popularly known as AR Rahman, is undoubtedly India’s most famous composer. He has won some of the world’s most coveted musical awards – including Oscars, Grammys and a Golden Globe. His song Jai Ho (May You Win), which won him an Oscar, became a celebrated anthem. The 59-year-old “Mozart of Madras” has also been honoured with Padma Vibhushan, India’s third highest civilian award, for his contribution to music.

But last week, when Rahman, a man of few words, shared in a TV interview that he potentially has lost work due to “communal” bias in Bollywood, India’s Hindi film industry, he was subjected to a massive online backlash from Hindu right-wing voices.

“People who are not creative have the power now to decide things, and this might have been a communal thing also but not in my face,” Rahman told the BBC Asian Network in the interview aired on Friday.

“It comes to me as Chinese whispers that they booked you, but the music company went ahead and hired their five composers. I said, ‘Oh, that’s great, rest for me. I can chill out with my family,’” he said in the 90-minute interview.

Right-wing commentators and activists questioned Rahman’s patriotism and talent, accusing him of playing the “victim card”.

Vinod Bansal from the far-right organisation Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) demanded an apology from Rahman for “defaming” the country.

Rising religious intolerance in India

But the backlash on social media continued for days, bringing into the spotlight the struggle of being a Muslim amid rising religious intolerance in India.

“Incredible to see Rahman being moved from the good Muslim to the bad Muslim category overnight,” Indian journalist Fatima Khan posted on X.

“Almost every Muslim public figure in India has had or will have the penny drop moment. No matter how many patriotic songs, movies or tweets. They’ll all live through the cruelty of it.”

Online trolling helps manufacture majoritarian consent, according to Debasish Roy Chowdhury, coauthor of To Kill a Democracy: India’s Passage to Despotism.

He argued that when enough noise is generated on social media, it seeps into mainstream coverage and starts to look like the dominant social mood.

“The loudest voices then drown out tolerance and reason until hate is all that is heard and can be falsely claimed as representative of society,” said Roy Chowdhury, who has written about Bollywood being used as a propaganda tool.

Hindu right’s influence on art and cinema

Rahman isn’t known for being outspoken about politics or talking about his Muslim identity. He has worked on a fair share of nationalist films, including Roja, released in 1992 and celebrated for its patriotic themes and portrayal of the armed rebellion in India-administered Kashmir in the 1990s.Rahman’s 1997 song Maa Tujhe Salam (Salute to You, Mother) on his album Vande Mataram was seen as unifying the diverse nation of 1.4 billion people.

The composer started his career in the southern Tamil film industry. He is based in Chennai, the capital of Tamil Nadu state.

The Oscar winner’s comments last week raised questions about the Hindu right’s influence on art and cinema in India, particularly in Bollywood.

The Hindi film industry has been called out for producing films that echo Hindu supremacist narratives, works that vilify Muslims and secular leaders, or even glorify Hindu extremists.

Some argued that this has happened because of a sustained culture war on Bollywood, pressuring it to abandon its pluralist, liberal ethos and pushing it towards Hindu majoritarian narratives, aligning cinema closely with the ruling party ideology.

The Kashmir Files (2022) triggered anti-Muslim hate across India while the Kerala Story (2023) was accused of spreading Islamophobia by portraying Muslims as potential “terrorists”.

More recently, Rahman composed music for the film Chhaava, which was accused of demonizing Muslims. The film portrayed Mughal ruler Aurangzeb as a brutal and violent ruler. Rahman, in his BBC interview, admitted the film was “divisive”.

‘Vilification of Muslims’

Raja Sen, a screenwriter and film critic, said: “We’re seeing a kind of vilification of Muslims on our screens.”

“Earlier, it was just like an anti-Pakistan narrative. Now, there’s a different kind of narrative,” he told Al Jazeera.

Hindi cinema has traditionally cast Pakistan as the enemy, focusing on topics of war, ‘”terror” and espionage, which are shaped by decades of hostility. The two neighbouring countries have fought several wars over the disputed Kashmir region. They were briefly engaged in a four-day war in May after gunmen killed 26 tourists in India-administered Kashmir.

Films that once centred on a foreign adversary now increasingly frame Indian Muslims as an internal threat.

Sen claimed that a major filmmaker changed an upcoming film’s Muslim protagonist’s name to a Hindu name, fearing controversy.

“They must have thought, why make the protagonist, a good, heroic guy, a Muslim. It’s perhaps similar to what used to happen in post-9/11 America in terms of how the stereotyping was being done,” Sen added.

Bollywood’s once largely secular ethos presented Muslim characters as positive, even if stereotypical. They were loyal friends, brothers or benevolent poets and singers in films like Amar Akbar Anthony (1977) and Coolie (1983).

In recent years, however, Muslims increasingly have appeared as debauched (Animal), regressive (Haq), “terrorist” (A Wednesday) or violent (Kalank), mirroring post-9/11 Hollywood films when Muslim identity became shorthand for danger or moral deficiency.