Antarctica’s Thwaites glacier at mercy of sea warmth increase

Antarctic glaciers may be more sensitive to changes in sea temperature than was thought, new research shows.

The British Antarctic Survey and the US Antarctic programme put sensors and an underwater robot beneath the vast Thwaites glacier to study melting.

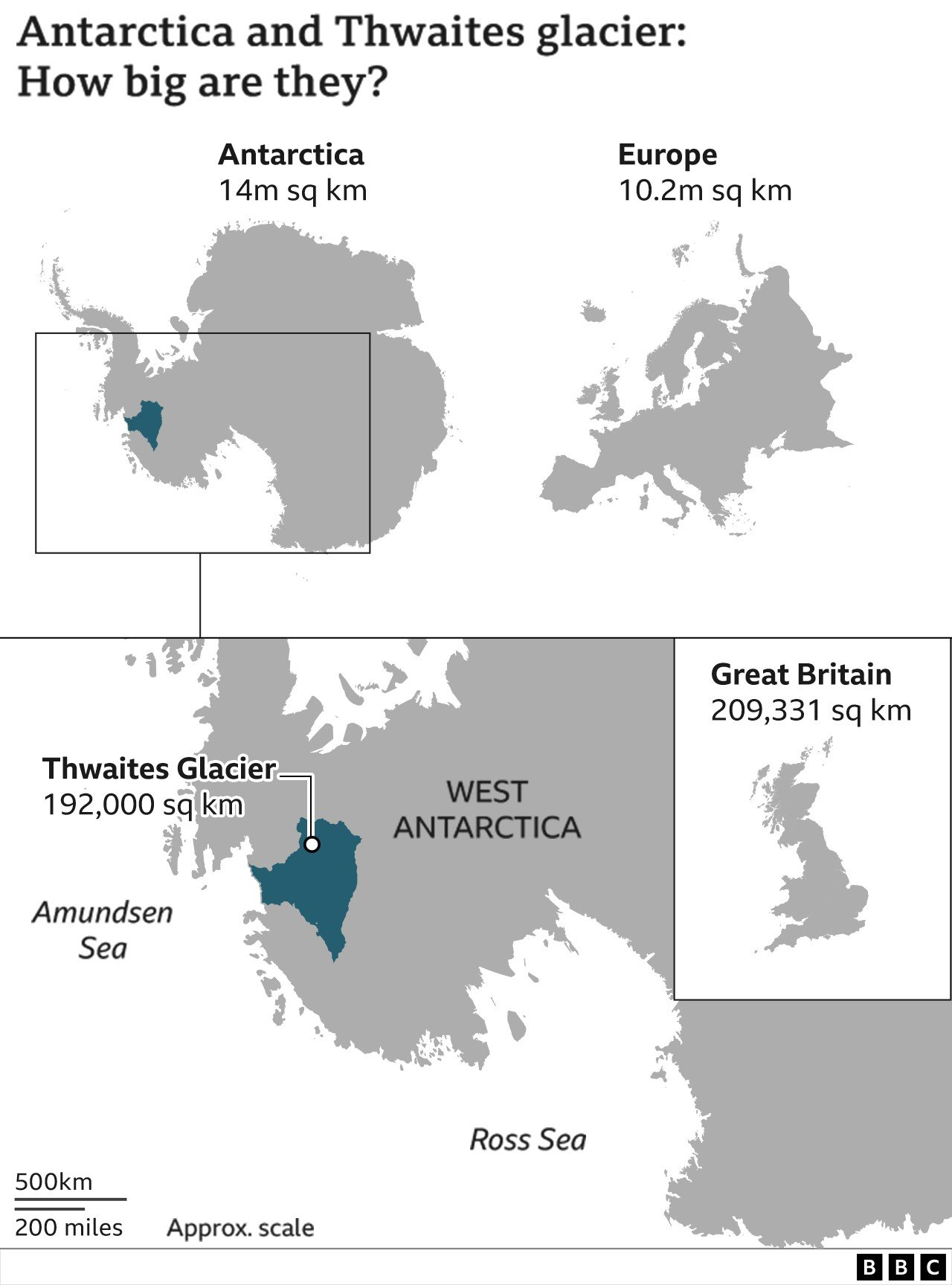

The size of Britain, Thwaites is one of the world’s fastest changing glaciers.

Its susceptibility to climate change is a major concern to scientists because if it melted completely, it would raise global sea levels by half a metre.

The new research suggests that even low amounts of melting can potentially push a glacier further along the path toward eventual disappearance.

The joint survey at Thwaites is part of one of the largest investigations ever undertaken anywhere on the White Continent.

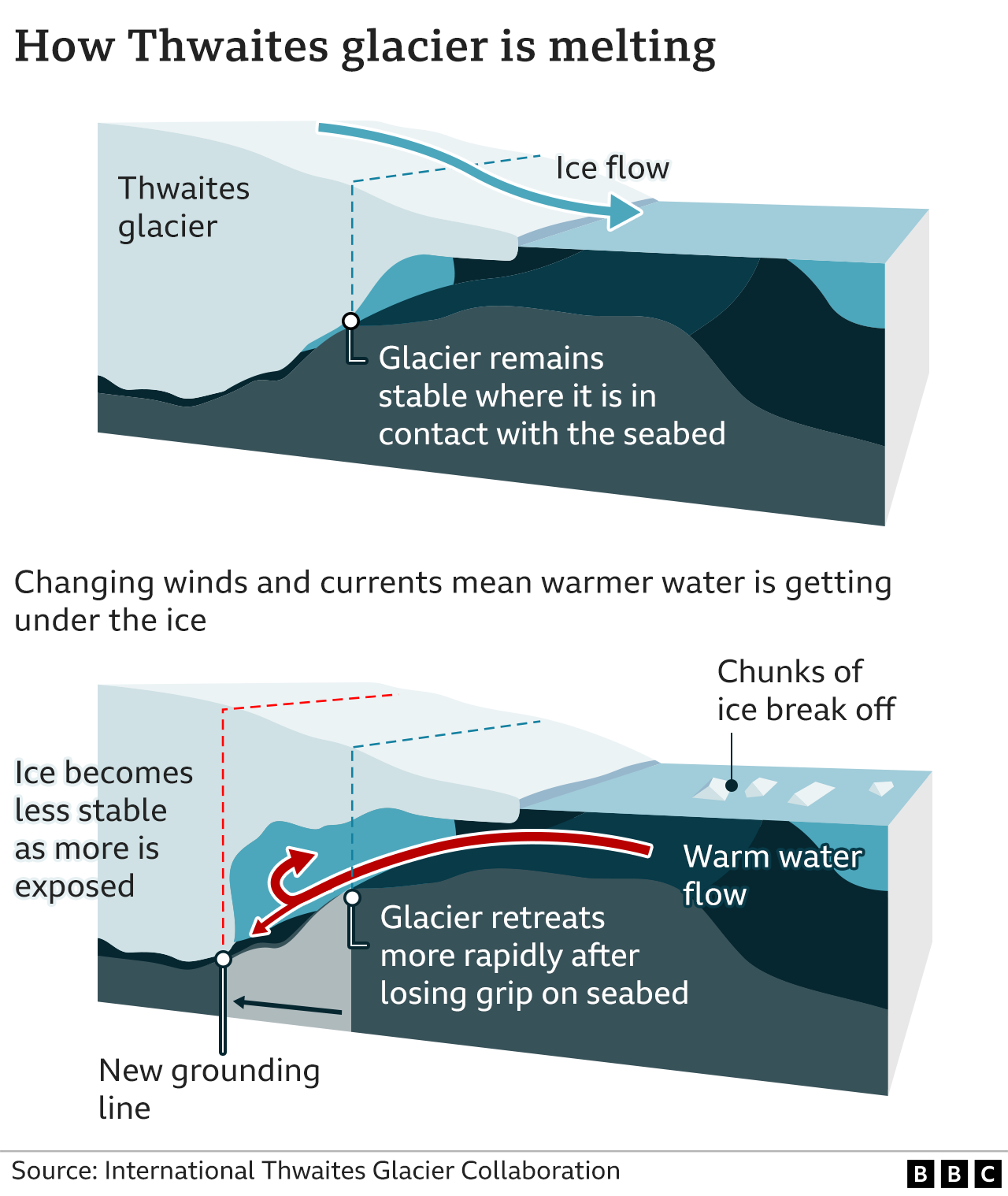

Since the late 1990s, the glacier has seen a 14km retreat of its “grounding line” – that’s the point where the ice flowing off the land and along the seabed floats up to form a huge platform.

In some places that grounding line is retreating now by over a kilometre a year, and because of the landward-sloping shape of the seabed, this process will likely accelerate.

During the new research, British Antarctic Survey (BAS) scientists dropped sensors through boreholes in the ice to the water below.

While warmer water circulates under the shelf, they found less melting than expected under those higher temperatures; a layer of fresh water was insulating against further losses.

But, worryingly, they also discovered with the help of computer modelling that the volume of melting was not the most critical factor in a glacier’s retreat.

“It’s good that the melt rate is low but what matters is how the melt rate changes,” explained BAS oceanographer Dr Pete Davis. “To push an ice shelf out of equilibrium, we need to increase the melt rate. So even if the melt rate increases just a small amount, it can still drive rapid retreat.”

The observations showing less melting than expected were taken from parts of the underside of the glacier that were flat and relatively uniform.

But images the underwater robot Icefin gathered for the US Antarctic programme as part of the same joint survey showed that things were often far more complex.

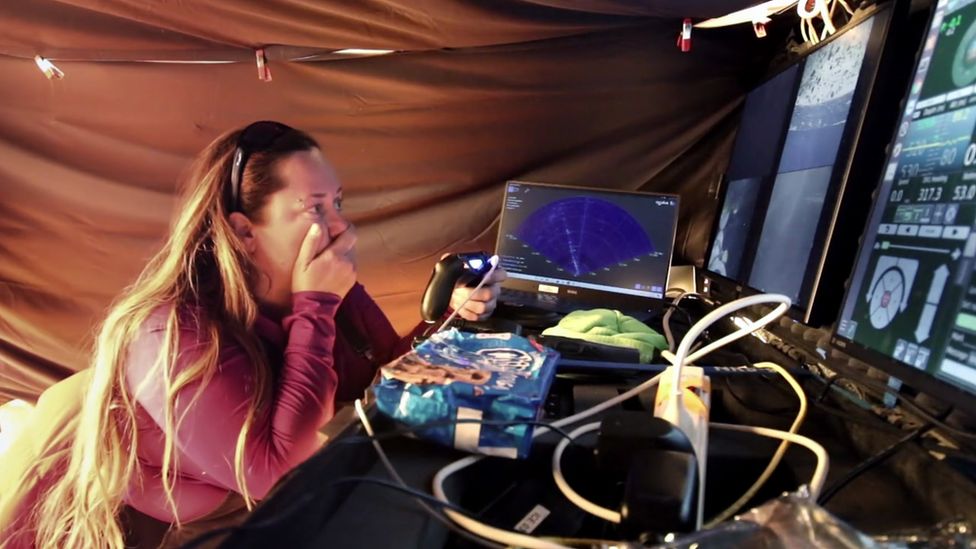

“What we could see is that instead of this kind of flat ice that we had all pictured, there were all kinds of staircases and cracks in the ice that weren’t really expected,” said Cornell University-based researcher Britney Schmidt, who guided Icefin under Thwaites using a video monitor and a games console controller.

To get the torpedo-shaped Icefin under Thwaites, the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) opened a narrow hole through 600m of ice with a hot-water drill. The tethered sub was then winched down to begin its exploration.

Dr Schmidt’s team conducted five separate dives, taking the robot right up to the glacier’s grounding line.

Icefin’s onboard sensors indicated that it is in these particular locations that the bottom of Thwaites is being eroded by the influx of warm water coming from the wider ocean.

“Basically, the warm water is getting into the weak spots and making them even weaker,” said Dr Schmidt. “What this allows us to do now is to put this kind of information into our predictive models to understand how the ice shelf is going to break down, and when.”

The lessons learned at Thwaites almost certainly apply to all the other glaciers in the region that are also in retreat, Dr Davis added.

Two scholarly papers describing the work are published this week in the scientific journal Nature. One focuses on Icefin, the other on the borehole profilers.

One of the contributing authors on the Icefin paper is Prof David Vaughan, the former director of science at BAS, whose death was announced by the polar agency last week.

Over 35-plus years, Prof Vaughan had built a formidable reputation as one of the world’s leading glaciologists.

He championed the UK-US Thwaites project and was its co-lead until stepping back because of illness.

His journey to see the research described in Wednesday’s two papers was his final expedition south.

Prof Helen Fricker, from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, is in Antarctica currently. She said: “David was a brilliant, thoughtful and engaging scientist who was a role model for so many. He was a leader in the field, making important geophysical insights about the Antarctic ice sheet and how it is changing.

“He led with dignity, grace, humour and compassion, and was actively supportive of young scientists, especially minorities. Antarctic science has lost a true hero and he will be deeply missed.”