Antarctica mysteries to be mapped by robot plane

A team of scientists and engineers have landed in Antarctica to test a drone that will help experts forecast the impacts of climate change.

The autonomous plane will map areas of the continent that have been out of bounds to researchers.

It has been put to the test in extreme weather around Wales’ highest peaks.

Its first experiment will survey the mountains under an ice sheet to predict how quickly the ice could melt and feed into global sea-level rise.

Scientists want to understand Antarctica better but they are limited by the existing technology.

Strong winds, below-freezing temperatures and sudden storms are common. These dangerous conditions, as well as dark winters and the need to transport pilots and large amounts of fuel, put limitations on use of traditional crewed planes.

The British Antarctic Survey developed the new drone with UK company Windracers to be easily repaired if something goes wrong.

The drone was tested in Llanbedr, Eryri (also called Snowdonia) in north Wales – a stand-in for the difficult weather and terrain of Antarctica.

During a practice run in strong winds with rain lashing the airfield, engineer Rebecca Toomey explained that the drone can fly to remote areas without concerns for pilots’ safety.

It can carry 100kg of cargo up to 1,000km. Instruments including radar and cameras are loaded in the back of the drone and on its wings. Its route is programmed in and an engineer monitors the flight from a computer.

Rebecca will operate the drone from Rothera base in Antarctica, but eventually the British Antarctic Survey hope to fly it from the UK.

It also uses much less fuel than traditional planes – 10 barrels compared to 200 on one research flight – reducing the environmental impact of scientific research on the planet.

The data it collects will be processed at the British Antarctic Survey headquarters in Cambridge.

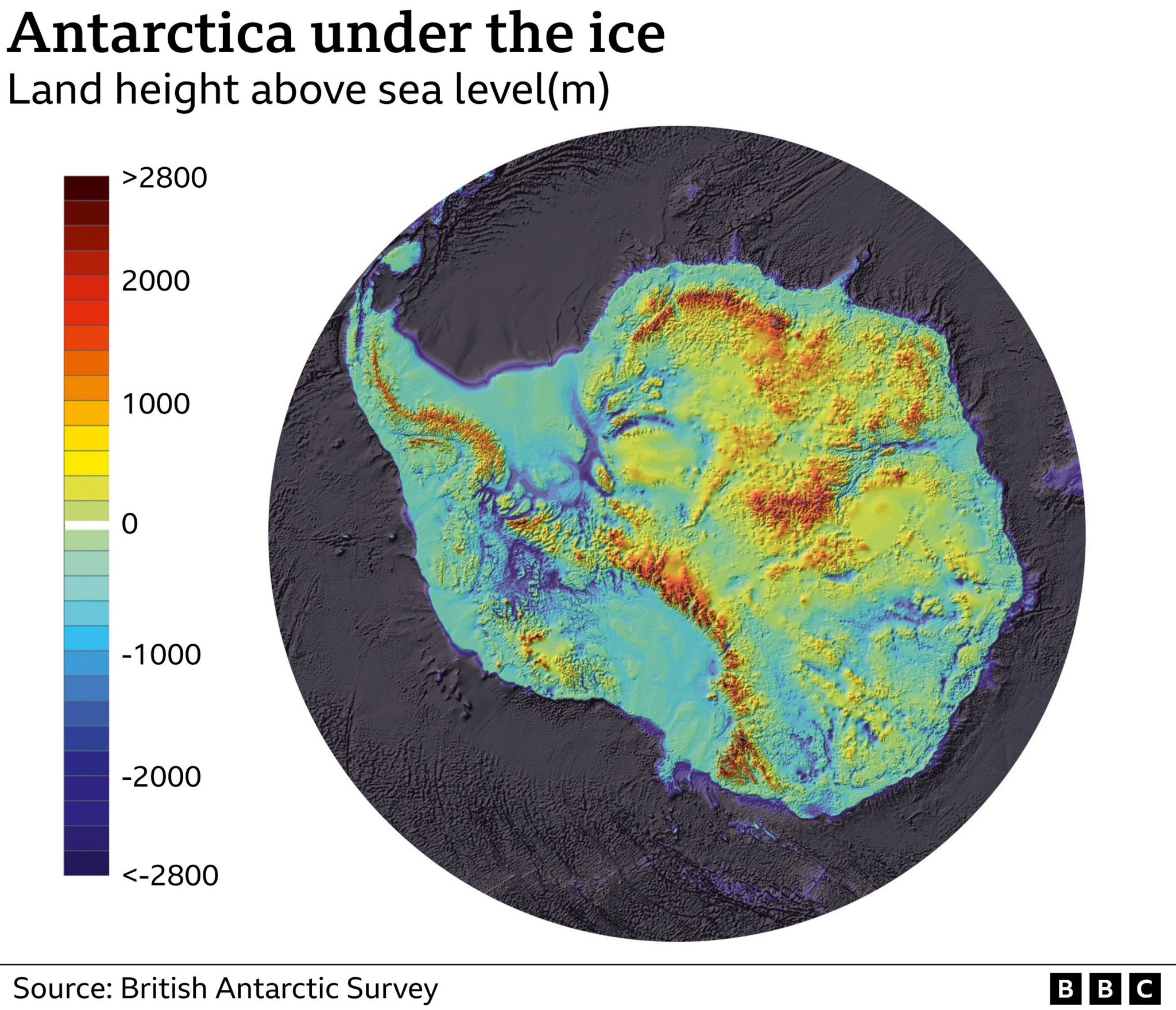

Scientist Tom Jordan explains that some of it will feed into a model of the continent called BEDMAP2 that shows the complex shape of the land under the ice.

Drawing a question mark over parts of the map, he explains that large areas of Antarctica are still unmapped because no-one has ever been able to get there.

“You can see the mountain ridge under the ice here and here. Does that continue across? Are parts under sea level? I don’t know,” he says.

“This survey work is really exciting because it’s a proper blank in the map.”

Antarctica’s vast ice covers huge mountains ranges – some the size of the European Alps – and trenches and valleys. Some areas are below sea level.

It is vital that scientists understand this topography because it determines how quickly the ice will melt.

An ice sheet exposed to warming waters will probably melt more quickly. But if complex mountains block its path, it will decline slower, Tom says.

In its first experiment, radar on the drone will fire radio waves at an ice sheet called Fuchs Piedmont. Some will go into the ice sheet, hit the ground at the base and bounce back. The drone will listen for those reflections and use them to draw the shape of the land.

“It builds up this picture – going line by line. This is another thing that drones are great for – doing things that are really boring,” he explains.

Current models of global sea-level rise from melting ice sheets have wide margins, but with a better understanding of Antarctica’s topography, Tom says scientists can make more accurate predictions.

“That will help us plan the future,” he says.

The first flights will be in the next few weeks. Other experiments include surveys of marine life like krill, which are a vital part of the food chain, and surveys of environmentally sensitive areas.