Aditya-L1: India successfully launches its first mission of the Sun

India has launched its first observation mission to the Sun, just days after the country made history by becoming the first to land near the Moon’s south pole.

Aditya-L1 lifted off from the launch pad at Sriharikota on Saturday at 11:50 India time (06:20 GMT).

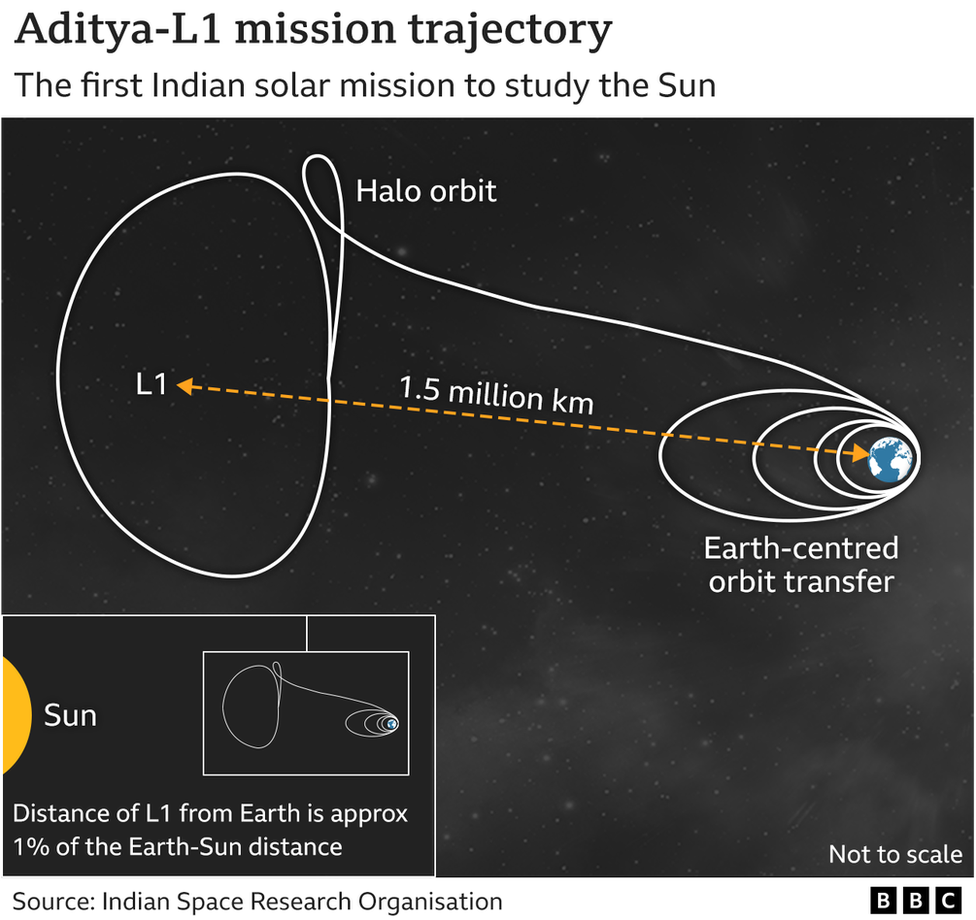

It will travel 1.5 million km (932,000 miles) from the Earth – 1% of the Earth-Sun distance.

India’s space agency says it will take four months to travel that far.

India’s first space-based mission to study the solar system’s biggest object is named after Surya – the Hindu god of Sun who is also known as Aditya.

And L1 stands for Lagrange point 1 – the exact place between Sun and Earth where the Indian spacecraft is heading.

According to the European Space Agency, a Lagrange point is a spot where the gravitational forces of two large objects – such as the Sun and the Earth – cancel each other out, allowing a spacecraft to “hover”.

Once Aditya-L1 reaches this “parking spot”, it would be able to orbit the Sun at the same rate as the Earth. This also means the satellite will require very little fuel to operate.

On Saturday morning, a few thousand people gathered in the viewing gallery set up by the Indian Space Research Agency (Isro) near the launch site to watch the blast off.

It was also broadcast live on national TV where commentators described it as a “magnificent” launch. Isro scientists said the launch had been successful and its “performance is normal”.

After an hour and four minutes of flight-time, Isro declared it “mission successful”.

“Now it will continue on its journey – it’s a very long journey of 135 days, let’s wish it [the] best of luck,” Isro chief Sreedhara Panicker Somanath said.

Project director Nigar Shaji said once Aditya-L1 reaches its destination, it will benefit not only India, but the global scientific community.

Aditya-L1 will now travel several times around the Earth before being launched towards L1.

From this vantage position, it will be able to watch the Sun constantly – even when it is hidden during an eclipse – and carry out scientific studies.

Isro has not said how much the mission would cost, but reports in the Indian press put it at 3.78bn rupees ($46m; £36m).

Isro says the orbiter carries seven scientific instruments that will observe and study the solar corona (the outermost layer); the photosphere (the Sun’s surface or the part we see from the Earth) and the chromosphere (a thin layer of plasma that lies between the photosphere and the corona).

The studies will help scientists understand solar activity, such as solar wind and solar flares, and their effect on Earth and near-space weather in real time.

Former Isro scientist Mylswamy Annadurai says the Sun constantly influences the Earth’s weather through radiation, heat and flow of particles and magnetic fields. At the same time, he says, it also impacts the space weather.

“Space weather plays a role in how effectively the satellites function. Solar winds or storms can affect the electronics on satellites, even knock down power grids. But there are gaps in our knowledge of space weather,” Mr Annadurai said.

India has more than 50 satellites in space and they provide many crucial services to the country, including communication links, data on weather, and help predict pest infestations, droughts and impending disasters. According to the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), approximately 10,290 satellites remain in the Earth’s orbit, with nearly 7,800 of them currently operational.

Aditya will help us better understand, and even give us a forewarning, about the star on which our lives depend, Mr Annadurai says.

“Knowing the activities of the Sun such as solar wind or a solar eruption a couple of days ahead will help us move our satellites out of harm’s way. This will help increase the longevity of our satellites in space.”

The mission, he adds, will above all help improve our scientific understanding of the Sun – the 4.5 billion-year-old star that holds our solar system together.

India’s solar mission comes just days after the country successfully landed the world’s first-ever probe near the lunar south pole.

With that, India also became only the fourth country in the world to achieve a soft landing on the Moon, after the US, the former Soviet Union and China.

If Aditya-L1 is successful, India will join the select group of countries that are already studying the Sun.

Japan was the first to launch a mission in 1981 to study solar flares and the US space agency Nasa and European Space Agency (ESA) have been watching the Sun since the 1990s.

In February 2020, Nasa and ESA jointly launched a Solar Orbiter that is studying the Sun from close quarters and gathering data that, scientists say, will help understand what drives its dynamic behaviour.

And in 2021, Nasa’s newest spacecraft Parker Solar Probe made history by becoming the first to fly through corona, the outer atmosphere of the Sun.