‘Remote coercion’: What has US approach been since abduction of Maduro?

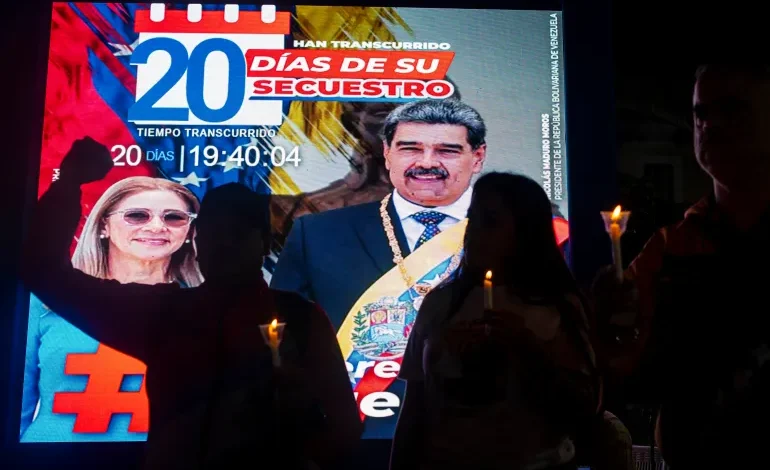

It was an extraordinary beginning to the new year: A deadly United States military operation on Venezuelan soil. The abduction of the country’s longtime leader, Nicolas Maduro.

But in the three weeks since the operation, widely condemned as an affront to international law and a potential opening salvo in the administration of Donald Trump’s stated goal of “preeminence” in the Western Hemisphere, only a vague framework of Washington’s plan for the South American country has emerged.

Meanwhile, relative calm in Venezuela has overlaid deep-seated anxieties over what comes next, analysts told Al Jazeera. Faultlines in the country’s leadership remain active, with the situation subject to devolve based on how Trump and his top officials proceed.

Here’s where things stand, and what could come next.

‘Operating with a gun to its head’

Maduro has sat in prison in New York since the January 3 operation, awaiting trial on drug trafficking and so-called conspiracy to commit “narcoterrorism” charges.

But many of the circumstances leading up to his abduction have endured. A massive portion of the US’s military arsenal has remained deployed off the coast of Venezuela. A blockade on US-sanctioned oil tankers has stayed in place. The Trump administration has promised to continue strikes on alleged drug smuggling boats in the Caribbean, while not ruling out future Venezuela land operations.

Trump initially promised to “run” Venezuela, while dousing the prospect of seeking to install an opposition-led government. He has continued to downplay the proposition of opposition involvement, following a meeting last week with Maria Corina Machado, instead focusing on coordinating with interim President and former Maduro deputy Delcy Rodriguez.

The president’s early manoeuvres, which have included his first direct call with Rodriguez and the deployment of his CIA director to Caracas, have unabashedly emphasised US oil access to the country.

In that, Trump has sought to establish a “control mechanism”, according to Begum Zorlu, a research fellow at City, University of London, that “depends on fear: sanctions, oil leverage, and the threat of renewed force”.

“What emerges is not governance but a strategy of remote coercion, forcing the post-Maduro leadership to comply with US demands, particularly around oil access.”

Or as Emanuele put it: “The Venezuelan government is operating with a gun to its head, and that cannot be bracketed out of any serious analysis.”

Emphasis on oil

In that context, the administration has made some early moves to access Venezuelan oil. Just days after Maduro’s abduction, Washington and Caracas announced plans to export up to $2bn worth of crude stuck at Venezuelan ports due to the ongoing US blockade.

Last week, the US announced the first $500m sale of the resource, with Rodriguez saying Caracas had received $300m in proceeds. She said the funds would be used to “stabilise” the foreign exchange markets.

But Phil Gunson, a senior analyst at the International Crisis Group focusing on the Andes Region, said the current scheme by which the US is acquiring and selling Venezuela’s oil remains opaque. Several questions – made the more pressing by a history of corruption and patronage in Venezuela – have gone unanswered.

US lawmakers, meanwhile, have demanded that Trump officials “immediately disclose any financial interests” they have in the companies involved.

“Selling the oil is the easy part,” he told Al Jazeera. “But who determines how that money is spent? How will the goods and services purchased be administered, by what criteria and under whose direction?”