Why sports stars who head the ball are much more likely to die of Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and motor neurone disease

Professional soccer players and American football stars are at much greater risk of developing dementia. What can we do to help them?

If you’re a football player, there’s nothing quite like the rush of leaping towards a ball hurtling towards you at great speed, heading it into the net, and scoring a goal for your team.

Yet evidence is mounting that repeatedly doing so can lead to brain damage that manifests decades later as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and motor neurone disease.

The dangers of contact sports have actually been known about for almost 100 years. In 1928, US pathologist Harrison Martland published a scientific article arguing that, “for some time, fight fans and promoters have recognised a peculiar condition occurring among prize fighters which, in ring parlance, they speak of as ‘punch drunk’.”

Symptoms included a staggering gait and mental confusion, and were most common in “fighters of the slugging type, who are usually poor boxers and who take considerable head punishment”. In some cases, punch-drunkenness progressed to dementia, later classed as “dementia pugilistica” – a type of dementia occurring in boxers who have experienced repeated head injury.

At first, it was thought the problem was confined to boxing. But in recent decades that understanding has changed. In 2002, West Bromwich Albion and England soccer player Jeff Astle died at the age of 59 following a diagnosis of early onset dementia. In the US meanwhile, American football player Mike Webster died suddenly age 50 after experiencing cognitive decline and other Parkinson’s-like symptoms. In both cases, examination of the sports stars’ brains showed they had died from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) – a more modern term replacing the diagnosis of dementia pugilistica.

There were other high-profile cases too. On 17 February 2011, former Chicago Bears player David Duerson died by suicide after suffering from depression. Subsequent analysis of his brain showed that he too had CTE.

“CTE is a really specific form of degenerative brain pathology, because we only see it in people with a history of head injuries or head impacts,” says Willie Stewart, a consultant neuropathologist at the University of Glasgow, UK.

The condition is also distinctive because if you look down a microscope you will see a specific pattern of abnormal protein deposits called tau in the brain.

“The best way of telling whether somebody might have CTE is to ask them the question ‘have you ever played football?’ or ‘have you ever played rugby?’ Because if you’re a professional footballer and you have dementia, then your chances of having CTE in your brain are very high,” says Stewart.

Since 2008, Ann McKee, a professor of neurology and pathology at Boston University School of Medicine, has been inviting former athletes to participate in research studies to learn how to diagnose and treat CTE. In 2023, McKee and colleagues analysed the donated brains of 376 former National Football League (NFL) players, and found a whopping 91.7% had CTE.

Heading the ball is also linked to other degenerative brain conditions

This cohort included former Philadelphia Eagles quarterback Rick Arrington, who played for the team between 1970-73, and former Kansas City Chiefs defender Ed Lothamer, who played in the very first Super Bowl. This does not represent the true risk of developing CTE amongst American football players, as people who suspect they may have the condition may be more likely to donate their brain to science. However for context the prevalence of CTE in the general population is thought to be less than 1%. McKee has also diagnosed CTE in former baseball players, cyclists and ice hockey stars. In all cases the common denominator was repeated knocks to the head.

However, it isn’t just CTE. Heading the ball is also linked to other degenerative brain conditions too. As part of the ongoing Football’s InfluencE on Lifelong health and Dementia risk (Field) study that he is running, in 2019, Stewart and his team examined the health records of nearly 8,000 Scottish former professional football players and compared them to 23,000 members of the general population.

“We took our footballers and matched them to people in the community who were born in the same year, and lived in roughly the same areas,” says Stewart. “For every footballer we had three matched controls, so that we had a good idea of what normal health and ageing should look like.”

The study found that former professional footballers are five times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease; four times more likely to suffer from motor neurone disease; and twice as likely to develop Parkinson’s disease compared to people of the same age in the general population. Overall, former professional footballers had a 3.5 times higher chance of dying due to neurodegenerative disease than expected.

“The risk is highest in positions where we see the most heading,” says Stewart. “So defenders are at much higher risk than other outfield players, and if you are a goalkeeper your risk is about the same as anybody else [in the general population].”

Stewart’s research has also shown that the longer a person plays professional football, the greater their risk, ranging from an approximately doubling of risk in those with shortest careers, to around a five-fold increase in those with the longest careers. Former international rugby union players are also at greater risk of neurodegenerative disease.

The head’s sudden change in speed during an impact causes the brain to ricochet around inside the skull

So what is it about heading the ball that is so damaging to the brain?

CTE tends to only be diagnosed after death, as it leaves tell-tale tangles of an abnormal protein called tau in the cerebral cortex of sufferers. However, Michael Lipton, a professor of radiology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center (CUIMC), has used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain scans to pick up early signs of the condition in young amateur football players.

“We enrol people who are over 18 and who are playing in some kind of an organised group – so it could be a university team, but more commonly it’s a recreational league,” says Lipton. “We have many people who don’t head the ball at all, and some who are heading the ball thousands of times a year.”

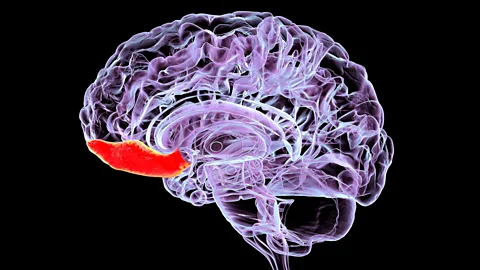

His research has shown that players who head the ball more frequently not only score worse on learning and memory tests, but also show clear signs of damage in the part of the brain just behind the forehead – an area known as the orbitofrontal cortex.

“It’s the part of your brain that is right above your eye sockets,” says Lipton.

The outermost layer of the orbitofrontal cortex, which is composed of white matter, appears to be particularly vulnerable.

“The white matter is like the network cabling of the human brain, which is composed of very fine filaments called axons which transmit information,” says Lipton.

These fine filaments are very vulnerable to being rapidly accelerated by a sudden force. The head’s sudden change in speed during an impact causes the brain to ricochet around inside the skull, stretching the axons, and disrupting their connectivity.

“If you think about heading the ball, the impact to the head is relatively mild – it’s not causing skull fractures or bleeding in the brain or obvious injury, but what it does have the potential to do is to cause forces to travel through the brain,” says Lipton.

In these relatively young, healthy people, there is something going on in their brain, but it’s not causing a disease at this point – Michael Lipton

“That force causes the brain inside the skull to move away from the site of impact. And the brain is extremely soft – almost the consistency of gelatin – and so when the brain is impacted like that, it will compress and twist and deform, and that puts strain on the axons.”

Subsequent research by Lipton and colleagues has shown that it is the gap between the white and grey matter in the orbitofrontal cortex which sustains the most damage from heading. The most frequent headers of the ball, who reported heading more than 1,000 balls per year had significantly greater damage in this area.

This is likely because grey and white matter have different densities and so move at different speeds when heading the ball. This creates shear forces between the two types of tissue.

What we don’t know is what happens next, however.

“Our research shows that in these relatively young, healthy people, there is something going on in their brain, but it’s not causing a disease at this point,” says Lipton.

Some of those individuals may go on to develop conditions like CTE, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s or motor neurone disease. But many won’t. As well as the number of times a person heads the ball in their lifetime, it could be that some people are more vulnerable than others due to a combination of genetics or lifestyle factors.

In those that do develop a neurodegenerative disease, one hypothesis is that repeated impacts to the brain could damage its blood vessels, or trigger a process of chronic inflammation that eventually leads to the disease.

“As a response to the fibre and blood vessel damage, the brain’s healing response [inflammation] kicks in to try and repair that,” says Stewart. “It may be that the vessels don’t really repair themselves properly, so they’re chronically leaky and letting stuff that shouldn’t be there get into the brain. Or it may be that the healing inflammation never really switches off the way it should do, and you end up with a chronic inflammatory process.”

Alternatively, it may be that injury to the neurons causes them to degenerate and die, causing more and more problems over time.

“It’s probably a mix of all of these leading to long-term problems, but that’s what we’re trying to unpick,” says Stewart.

So what can we do to protect athletes and amateur sports players from dementia in later life?

Technology may be able to help. For example researchers at Stanford University in California are designing American football helmets with built-in liquid shock absorbers, which reportedly reduces the impact to the head by about 30%.

Cutting down on heading the ball could also play a role. In the UK, as a consequence of Stewart’s research, heading has been removed from youth level football. His group has also campaigned successfully to reduce the amount of heading that takes place during the week in training sessions.

“What we found when we chatted to footballers was that they might have headed the ball 70,000 times during their career. But only a couple of thousand of those were during matches.”

“That’s 68,000 head impacts during the week that nobody’s paying attention to, so let’s get rid of as many of those as possible.”

However as always, prevention is the best cure.

“If we just stopped banging our heads against things, then the risk would disappear to zero, but in practical terms, it’s hard to convince people to do that,” says Stewart.