The woman who gave her life to save the gorillas

Dian Fossey transformed our view of mountain gorillas while fighting tooth and nail to save them. But according to the people who knew her, she was also a flawed obsessive whose murder remains a mystery to this day.

It is now 40 years since the mysterious murder of Dian Fossey, the primatologist who transformed the way we see gorillas.

Before Fossey’s work, gorillas had an appalling reputation as violent brutes that would kill a human on sight. Fossey demolished this myth. Living alongside a group of mountain gorillas in the forests of Rwanda, she showed that these huge apes are actually gentle giants, with individual personalities and rich social lives. In many ways they are like us.

But the mountain gorillas were also in terminal decline, their habitats encroached on by farms and overrun by war and civil unrest. Fossey spent her last years embroiled in an increasingly savage battle to save them, until she was murdered in her cabin in 1985. Her murderer and the reason for her death remain a mystery.

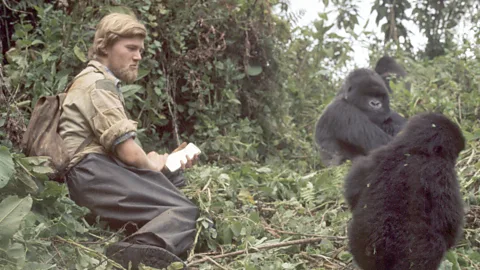

The 1988 film Gorillas in the Mist presented a fictionalised version of Fossey’s story. We have attempted to tell it as it really happened by speaking in depth to three of Fossey’s colleagues and friends, one of whom, Ian Redmond, provided nearly all the photos featured.

Dian Fossey did not set out to become a primatologist. She simply loved African nature and was inspired to travel to the continent in 1963.

During this trip she met the renowned palaeoanthropologist Louis Leakey. He was focused on studying the fossils of our ancestors, but had realised that to really understand how humans had evolved, we would also have to learn about our closest relatives: the apes.

Leakey had already helped Jane Goodall set up long-term studies of chimpanzees. Now he wanted to start something similar for gorillas.

At the time little was known about mountain gorillas, one of two subspecies of the eastern gorilla. In films they were depicted as violent brutes and tales from hunters suggested that if anyone got too close, they would charge to kill.

Content warning

This article contains images and descriptions of violence that some readers may find upsetting.

Three years after their meeting, Leakey hired Fossey to study mountain gorillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo. But conflict in the country forced her to leave.

So in September 1967, Fossey set up a small research outpost in neighbouring Rwanda: the Karisoke Research Center. This consisted of a few cabins high in the volcanic Virunga mountains.

The area was and is home to the Virunga group of mountain gorillas. This is one of only two populations in the world, the other one being in Uganda.

There were about 475 individuals in the early 1960s, but their numbers were dwindling due to poaching and habitat loss. In the early 1980s the population dropped to about 254 individuals.

Fossey set out to understand and protect the few remaining mountain gorillas, before they disappeared. Her early work was painstaking. To get close to the gorillas, she started imitating their behaviour.

As she explained in 1984: “I’m an inhibited persona and I felt that the gorillas were somewhat inhibited as well, so I imitated their natural, normal behaviour like feeding, munching on celery stalks or scratching myself.” She would also beat her chest with her fists and copy their belch-like calls.

Fossey’s patience and quiet demeanour paid off. She gained the gorillas’ trust and could observe them undisturbed. She soon started to see which gorillas belonged to which family, and learnt the key role played by the dominant “silverback” male in each family.

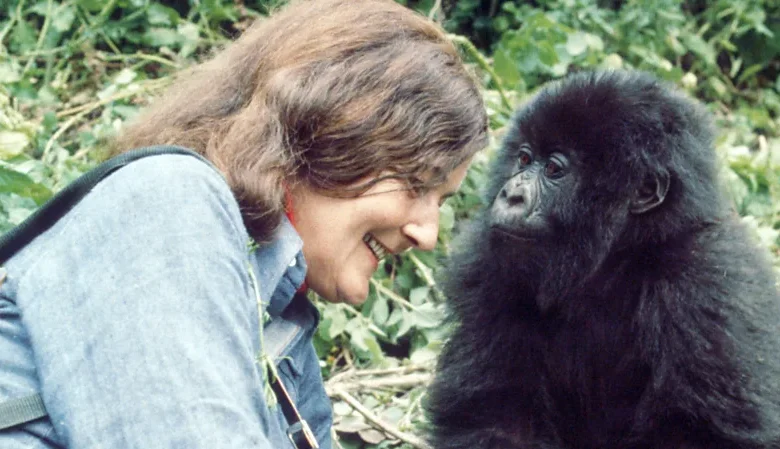

This method of gaining their trust is called habituation. It was Fossey’s great gift to the world, says gorilla conservationist Ian Redmond, who worked closely with her for over three years. Eventually it led to human-gorilla friendships.

“I mean that seriously,” says Redmond. “Gorillas are so like us and they can see they’re like us. They are as fascinated by us as we are by them. They actually inspected us physically, pulled our lips down and looked at our teeth. They were very curious about this gorilla-like animal that does such different things [to them].”

In 1970, only three years after starting her fieldwork, Fossey appeared on the cover of National Geographic magazine. On the pages inside, she first told the world about the lives of mountain gorillas.

“The gorilla is one of the most maligned animals in the world,” Fossey wrote. “After more than 2,000 hours of direct observation, I can account for less than five minutes of what might be called ‘aggressive’ behaviour.”

The world immediately took notice. “Here’s this lone woman out in the centre of Africa studying what others would have presumed were fearsome dangerous creatures,” says Amy Vedder of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies in New Haven, Connecticut, US, who worked with Fossey from early 1978.

For the first time, gorillas were captured on film for people to watch in their own homes.

Fossey also named the gorillas she studied and shared their characteristics, just as Jane Goodall had done with chimpanzees. “That was greatly inspiring. It created a global level of interest and concern about gorillas,” says Vedder.

She demanded complete loyalty, but you never knew whether she was going to love or hate you that day – Kelly Stewart

Living in a remote area with few other people around suited Fossey well. But that was not true of everyone who worked there. At night the forest creaked and groaned. It could seem like a terrifying place, Redmond says.

Fossey provided little companionship or comfort. She was not an easy person to live and work with. She often preferred to be alone, according to those who worked with her. She could be extremely charming and charismatic one minute, then hostile the next. Days went by where she barely communicated with anyone except for sending around hand-written notes.

Her friend and fellow primatologist Kelly Stewart spent many years working with Fossey, initially as her student.

She was a hard person to be friends with, Stewart says. “She demanded complete loyalty, but you never knew whether she was going to love or hate you that day. She could be very charming, a lot of fun, and very supportive. And then she could turn on you.”

By the time Stewart arrived in 1973, Fossey was not spending much time with the gorillas. She was suffering from emphysema, which made her very short of breath. Despite this, she still had full control of the research camp, Stewart recalls.

Fossey also spent ever more time dealing with poachers and farmers, whose cattle encroached on the gorillas’ habitat. Shortly after Stewart arrived, Fossey shot several of the cattle dead.

“When I first got there she was mercurial but was already angry,” Stewart says. “She was in warrior mode and fighting mode. Her love for gorillas and her hatred of poachers really coloured her behaviour, and some people think it eventually got in the way of rational management of the research centre.”

She bought facemasks and pretended to use black magic

Fossey’s conflict with the poachers was to take up a large part of her life, overshadowing some of her other efforts.

There are reports that she would capture and interrogate them. She bought facemasks and pretended to use black magic, so locals might think she was a witch and be scared off. Some locals referred to her as “the witch of the Virungas”.

There are also anecdotes that she arranged for some poachers to be tortured. Fossey later recounted one of these incidents in a letter to a friend: “We stripped him and spread eagled him and lashed the holy blue sweat out of him with nettle stalks and leaves…”

There were other incidents that raised questions about her tactics.

“There was one occasion when Dian accompanied local police to arrest a poacher at his home outside the park (a small thatched hut),” says Redmond. “He was not there but Dian helped the police search for where he had hidden his gun. The poacher’s wife and family refused to hand over the gun. In the heat of the moment, Dian grabbed a boy and said, ‘hand over the gun and I’ll let the boy go’. Unfortunately, the family fled leaving Dian with the child.”

Fossey took the boy to her camp at Karisoke where Redmond looked after him for a couple of days, ensuring he was well fed and treated well. Redmond says Dian was later fined for the incident. It has been used as an example of some of the more extreme methods Fossey used in her fight against poachers, but Redmond says it wasn’t something she had intended as a tactic against the poachers. “It was a foolish thing to do in a dramatic moment, but it was never repeated,” he says.

Fossey was fighting a battle that, as far as she could see, she was losing. Gorilla numbers continued to decline. Worse, her increasingly militant antics gained her many enemies.

Among the gorillas she habituated, Fossey had one favourite. His name was Digit, so called because of his crooked finger. She knew him as he was growing up and felt a special bond with him. Just like her, Digit was a bit of an outsider.

On New Year’s Eve in 1977, Digit was killed by poachers as he tried to defend his family. He was only 12 years old.

It was Redmond who found Digit shortly after he was killed. He had been decapitated and his hands cut off. They were reportedly sold as trinkets for about $20 (£12 at the time). Redmond brought his “mangled” body back to camp, where it was buried.

It was a devastating blow for a woman on an increasingly personal mission to take on poachers. “The mutilated body, head and hands hacked off for grisly trophies, lay limp in the brush like a bloody sack… For me, this killing was probably the saddest event in all my years of sharing the daily lives of mountain gorilla,” Fossey wrote in a 1981 article in National Geographic.

After Digit’s death she spent more time on her own in her cabin and rarely communicated with colleagues and friends. Her drinking and smoking – already heavy – became heavier. She spiralled into a terrible depression.

Six months later there was another, more organised attack on Digit’s family. Two others were killed and an infant, Kweli, was wounded and later died from his injuries. One of those killed was Uncle Bert, the group’s dominant silverback. Gorilla families depend heavily on their leaders, so his death was devastating to Digit’s family.

“Kweli died from bullet-wound complications combined, I think, with acute depression. He was buried between his mother and father, who lay next to Digit. All three adults, in effect, had died so that he might live,” Fossey wrote.

She blamed these killings on the local government. “Dian felt it was because the authorities wanted a dramatic story for the world to respond to,” says Redmond.

The publicity around Digit’s death may even have inspired others to get a quick buck from poaching, Fossey thought at the time. She also had a suspicion that the authorities “had been instructed to kill a gorilla” to gain sympathy and funding from conservationists.

Digit’s death did raise awareness of the gorillas’ plight and, crucially, more money. But most of the money went into other forms of conservation, rather than directly tackling poaching as Fossey wanted.

“For a long time there was a real falling-out between Dian and the other conservationists because she was in the forest and there was no sign of any change, poachers were operating, snares had been set, gorillas were in danger but she was seeing money being spent on education and films,” says Redmond.

The other conservationists were playing a long game. They were aiming to raise awareness of the gorillas and to encourage the local government to keep their habitat intact, rather than using it to raise cattle.

Fossey believed this was the wrong approach. She wanted direct action and to see poachers imprisoned. She could not see that these people, who were part of the problem, could ever be part of the solution. She “derided the efforts to convert poachers into farmers”, says Redmond.

Her hostility and mistrust towards the Rwandans deepened.

Vedder, who arrived only two months after Digit was killed, says that Fossey did not believe any Rwandan would be sincere or smart enough to help. “She shut them out entirely. She was extremely dismissive of them,” Vedder says.

Fossey did not seem to realise that, to save the gorillas, she would need all the help she could get, including from the authorities she despised. She refused to work with those proposing new methods of conservation, arguing that any efforts that did not focus on poaching were wasted. She was known to call it “comic book conservation”.

Fossey therefore kept her distance from the Mountain Gorilla Project, which began in 1979 and saw several organisations come together to save Rwanda’s remaining gorillas. The key was working with locals to change their attitudes towards the gorillas.

On 26 December 1985, Dian Fossey was hacked to death with a machete. To this day, her murder remains unsolved. Redmond, who arrived at her cabin shortly after her death and could still see blood stains on the carpet, says that the investigation was poorly handled.

“There wasn’t a scene-of-crime approach to it,” he says. “People were tromping around, damaging footprints and evidence.”

She could not see that these people, who were part of the problem, could ever be part of the solution

One thing was clear: whoever killed Fossey also ransacked her cabin as if looking for something, but did not take any valuables. The obvious explanation is that she was killed by the poachers she had battled for so many years. But those who worked there dismiss this as a possibility.

Poachers were local hunters who had lived this way for decades, using any earnings to provide for their families. They knew that what they were doing was illegal, so they would stay out of sight, says Vedder.

“The last thing they wanted was a confrontation. I strongly believe, though no-one has evidence, it was not poachers. Poachers were rural people with few means and did not know the camp well enough to be a threat to her.”

Others believe local gold smugglers were responsible.

The Karisoke Research Center lies near Rwanda’s borders with the Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda, close to areas that have endured years of unrest. That made it an ideal route for smugglers. Reportedly, Fossey had evidence of this and the smugglers wanted to retrieve it.

Fossey knew her life was in danger and slept with a pistol near her bed. Many were surprised she had not been killed earlier, says Stewart. “She really did have enemies, her behaviour could be extreme and violent things happen in that part of the world.”

It was a fitting end to a life full of confrontations, says Stewart. “If Dian had been writing a movie script about her life, that’s how she would have ended it. Being murdered in her cabin was like dying like the warrior she was… I think she would have approved of that ending.”

News of her death took a while to circulate back to those who knew her. Of her earlier colleagues, only Vedder happened to be in the country at the time. “I laid thistle and celery [gorilla food] on her grave,” she recalls.

Shortly before she was killed, Fossey said to Stewart that there would be no mountain gorillas left within 15 years. She was wrong. A census one year after her death revealed that their numbers had slowly but steadily been increasing.

Fossey was murdered before she could learn that her work had paved the way for mountain gorillas to begin recovering. Her research laid the foundations for much of what has since been learned about gorillas, allowing the creation of a successful and well-managed conservation and ecotourism industry.

The 1990s saw the horrors of the Rwandan genocide, but throughout this dreadful period the gorillas’ numbers stayed relatively stable. “I think that’s part of Dian’s legacy, too,” says Stewart. “I think she kept it going in the forest, if it [the research centre] hadn’t been there so long, I think it’s possible that the Mountain Gorilla Project wouldn’t have started.”

Even today, mountain gorillas are believed to be one of the few apes whose numbers are not in decline. They remain endangered but less than a decade ago they were classified “critically endangered”. An annual naming ceremony of baby gorillas in Rwanda recently celebrated its 20th anniversary and since 2005 over 400 baby gorillas have been celebrated at the ceremony. Today there are an estimated 1,063 mountain gorillas left in the wild, a steady rise since 2012, which put the total number at 880.

Despite all her faults and mistakes, her hostility towards the local government, poachers, her friends and her reluctance to work with other conservationists, it was Fossey who first put the Rwandan mountain gorillas on the map. Arguably, she deserves a lot of credit for the slow recovery of the mountain gorillas.

“If people hadn’t known about her from her National Geographic articles, when Digit was killed it wouldn’t have made such a splash,” says Stewart.

Fossey was buried in the Virunga mountains where she spent 18 years of her life. Next to her lies her “beloved Digit”.