‘The sound completely changes’: To electrify boats, make them fly

Born from a desire to make boats go faster, today the hydrofoil is being revived as a cleaner form of water transport by helping boats rise above the waves.

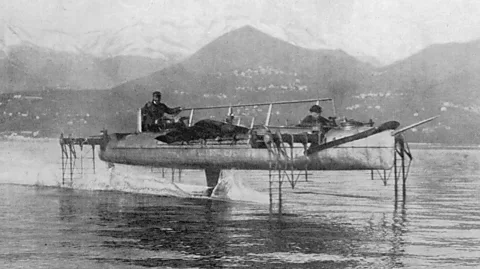

It would have made an unusual sight in 1860s France – a rowing boat rising and appearing to float high on the water, a series of wedges helping to raise its hull upwards as its occupant pulled hard on the oars. It’s not known if this hydrofoil boat was ever built by Parisian inventor Emmanuel Denis Farcot, who filed the first patent for a vessel of this kind in 1869. What is clear, however, is that over the next 50 years others would succeed in “flying” a boat above the water.

Italian inventor Enrico Forlanini floated a working hydrofoil boat on Lake Maggiore in the Italian Alps in 1906. Canadian Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone, also developed several hydrofoil technologies in his quest to design an early aeroplane. Bell’s fourth hydrofoil vessel, known as HD-4, was clocked travelling at more than 70 mph (113 km/h), which broke a world speed record for watercraft and held onto the title for a decade.

“In the early 1900s, people were experimenting with hydrofoils and they gave the craft some interesting characteristics, like higher speed, low drag – seakeeping characteristics that are different from other types of boats,” says Jakob Kuttenkeuler, professor of naval architecture at Sweden’s KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

In the 1960s there was another boom in interest in hydrofoils, making use of some of these characteristics discovered earlier in the century. “People wanted to go faster,” said Kuttenkeuler.

Now, the hydrofoil is seeing another resurgence – this time, for its potential to reduce emissions from small boats, such as ferries. “Today, the driving force for going hydrofoil is electrification,” says Kuttenkeuler.

Early hydrofoils ran on fossil fuels and were built with heavy metal bodies. Their double edged, V-shaped foils allowed them to move much faster than traditional hulls, but still caused considerable drag. By the mid-20th Century, hydrofoil technology had gone as far as it could with the materials, energy sources and technology available at the time.

But hydrofoils have had a modern comeback of sorts, Kuttenkeuler says, largely due to new technological advancements. That includes smaller, more efficient batteries, lightweight building materials, and microcomputers that run sensors which automatically balance hydrofoils, allowing the newer style to replace the clunky self-adjusting V-shaped foils for a streamlined single foil that raises the boat’s hull fully into the air.

Kuttenkeuler, who invented the eFoil, a board attached to a hydrofoil that people can ride smoothly on top of water, is optimistic about the potential uses for the hydrofoil. Today you can see sports enthusiasts and billionaires like Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg cruising around on a commercialised version. Kuttenkeuler has been called the “godfather of hydrofoils” and has spent years researching the benefits and drawbacks of the technology among other maritime vessels.

But the hydrofoil is not just changing watersports, it is also capable of raising entire ferries out of the water in an effort to significantly reduce their emissions.

Electric ferries

Engineer Gustav Hasselskog remembers being struck by the extraordinary quantities of fossil fuel used by an old boat he kept at his summer home in Vindö, Sweden. He calculated the boat was consuming around 15 times more fuel per kilometre than his car. It was 2014, right around the time electric vehicles were poised to take off globally, and it got Hasselskog thinking.

“Nobody has done anything seriously, really, on electrifying boats,” says Hasselskog. “And so I started to look into what can be done.”

The problem with electric vessels is that batteries contain much less energy per unit of weight than fossil fuels. Traditional boats need a lot of energy, because their hulls create significant drag in the water. But after some research, Hasselskog came across hydrofoils. Lifting the hull out of the water reduces drag, and cuts the energy required to propel the vessel forward. Some hydrofoils can reduce a vessel’s energy consumption by up to 80%.

Hasselskog realised the technology could be a breakthrough for cleaner and faster public transportation. That same year in 2014, he founded the company Candela, which this past summer chartered its first trial of all-electric hydrofoil ferries in Stockholm, as part of a short-term pilot project. If taken up by the city of Stockholm permanently, Hasselskog hopes Candela could eventually replace traditional ferries throughout the city and elsewhere.

Alongside lower emissions and higher speeds, electrified hydrofoils create very little wake and don’t rise and fall with the waves in the same way as a conventional boat – meaning no sea sickness. And the technology is now spreading globally, with communities from India to Seattle looking to adapt hydrofoiling for public and private clean-energy transit.

Sporting chances

Hydrofoiling’s recent popularity owes much to competitive sports. Sailboat races such as the America’s Cup have started incorporating hydrofoils, which experts like Kuttenkeuler credit with “energising” the technology’s resurgence. In the 2024 Paris Olympic games, hydrofoils were used in windsurfing and kitesurfing events.

Laura Marimon Giovannetti, a senior researcher and project manager at Rise, Sweden’s state-owned research institute, and a sailor herself, says that after the America’s Cup in 2013, “it was clear that technology from the material side was good enough with the use of composite materials and at the same time there was the push for electric propulsion as well”. Between 2017 and 2020, several technical factors came together to advance the technology, she says: improvements in battery size, storage, electric engines, sensors and lighter materials.

Today hydrofoils are typically built with a blend of carbon fibre and metals like titanium, says Giovannetti. The technology has permanently altered the landscape for sailing because of the speeds the boats can get up to, Giovannetti says. For her, it’s hard to go back. There’s a reason, she points out, that engineers say the boats “fly” on water – the hydrofoil serves a similar function in water as an aerofoil does in air.

“Literally, they’re wings underwater,” says Giovannetti of the craft. “When you suddenly foil, it becomes completely silent. The sound completely changes. If you hear any sound, it’s more of a whistle that comes only from the foils themselves being fast in the water.”

Scaling the technology

Small ferries may have made it above the water with the help of a hydrofoil, but doing the same with larger vessels is challenging. In order to reach top speed and be the most energy efficient, hydrofoil vessels must stay smaller, both in size and weight. One pitfall of the technology, according to Hawsselskog, is that hydrofoils must stay fairly small otherwise they lose their speed advantage and traditional boats become more efficient. They also can’t go long distances without being charged. Another risk is encountering a solid underwater object – some hydrofoils have been designed with sensors that can tell if the boat is approaching something it could hit, like a log or a sea lion.

Despite the drawbacks, the vessels are seeing uptake. Hasselskog says Candela has already sold 11 ferries to private operator JalVimana in Mumbai, India, where it is hoped they will significantly cut travel time on several routes. On the journey from Mumbai to the Navi Mumbai airport, a hydrofoil is expected to cut the commute from 1 hour 45 mins to 30 mins. The first vessel is expected to begin operation in 2026. Candela also sold eight hydrofoils to Saudi Arabia for use in the Red Sea for development of its planned linear city called the Line. The company recently sold 14 ferries to touristic resorts in the Maldives and Belize. In the US it sold four ferries to a private operator in Tahoe City, California, to carry passengers across the lake.

Separately, Kitsap, a county just outside Seattle, Washington, recently put out bids to build a prototype hydrofoil that could carry 150 passengers and run on a roundtrip commuter ferry route to the city’s downtown, about 12 miles (19km) each way. There’s a US regulation that public transportation projects receiving federal funding must use American-made products. Kitsap received a $372,910 (£279,400) federal grant in 2021 to research the feasibility of developing an all-electric hydrofoil that could carry 150 passengers and cause little wake. It received another grant from the Department of Commerce in 2024 for $1.2m (£900,000) to design a pilot electric hydrofoil and $5.2m (£3.9m) from Washington state to design and build the zero-emission fast ferry and shoreside charging infrastructure.

Part of the design criteria was building a vessel that could absorb or avoid hits to floating logs in the Puget Sound, according to Kitsap Transit executive director John Clauson. He says the ferries will also be equipped with the same warning system all boats use to avoid pods of traveling orcas. It’s hoped hydrofoils could travel faster than conventional ferries along the coastline without causing disruption from their wake.

The route is expected to take 30 minutes, down from the hour it takes to ride on the traditional car-carrying ferries, says Clauson – although these will only carry foot passengers. Once built, the hydrofoil expected to take 20 minutes to recharge. It’s not yet determined when the ferries could be in use publicly.

“We do have the occasional naysayers that don’t understand the technology, or they bring up issues about what’s going to happen if you get a log and that sort of thing, but generally the community has been very supportive,” says Clauson.

In Stockholm, Hasselskog has so far focused on a specific two-hour route from Ekerö, an idyllic suburb west of Stockholm, to Stockholm’s City Hall, a 12-mile (20km) route. The traditional ferry carries 250 people and takes about 55 mins. Instead, each Candela ferry can carry 30 people at a time and takes under 30 mins travelling at a top speed of 30 knots. He estimates that by instead running three Candela ferries and increasing departures per day from nine to 23, they would be able to shuttle 15% more commuters.

The technology’s main limitations, Hasselskog says, are that the ferries can’t travel more than about 40 nautical miles, and their batteries take about an hour to charge.

With Candela’s limited summer trial-run in Stockholm over, the city must now decide whether to move ahead with purchasing the hydrofoil ferries and incorporating them into their working fleet. Candela estimates that the ferries ultimately would save the city 40% in costs. That was one of the biggest selling points to Stockholm and others he’s spoken to, says Hasselskog. “You can go to private operators and convince them, on a financial aspect, that this is the right thing to do,” he says. “You can save money.”