‘It was the start of a new movement’: The Dutch rewilding project that took a dark turn

In 2018, thousands of dead animals, emaciated from starvation, lay strewn across a famous Dutch rewilding project. Was it animal cruelty or just nature taking its course?

In February 2018, train commuters travelling between the Dutch cities of Almere and Amsterdam were horrified to see animal carcasses strewn across the landscape. They were passing by the Oostvaardersplassen, one of Europe’s most infamous rewilding projects, known for its diverse birdlife and wild cows, deer and horses.

For many years, beginning in the 1980s, the ethos at the Oostvaardersplassen was not to intervene and to allow nature to take its own course. The pioneering approach helped shape the conversation around rewilding and influenced nature restoration projects across Europe.

But this approach took a dark turn during the harsh winter of 2017-18 when thousands of cows, horses and deer ended up being shot before they starved to death, sparking huge public backlash. The landscape at that time more closely resembled a desolate wasteland than a vibrant conservation area. Bones were scattered across the blackened ground and there were no trees or shrubs to be seen.

“It was a completely different sight… a monotonous grassland,” says Hans-Erik Kuypers, the park ranger from Staatsbosbeheer, the national forestry service, who is guiding me around the reserve.

Seven years later, I am walking through the Oostvaardersplassen. None of what Kuypers describes is visible. He points out an astonishing array of birdlife, wading through clear pools of water, and clusters of elder, willow and hawthorn trees dotting the landscape.

A white-tailed eagle glides through the sky. A herd of sleek wild horses roll in the grass. Large bulls graze on lush vegetation, against a backdrop of windmills. The air is filled with birdsong. It’s difficult to believe that we are just a 40-minute drive from the buzzing centre of Amsterdam.

The events of 2018 led to a change in management; the rangers now actively intervene to prevent starvation. They plant trees, feed the animals if needed, and keep the overall numbers in check. But some still argue that this is unnatural – and that the reserve should be left free of human intervention.

“There are still some people who think we should be doing it differently,” says Kuypers. “[Rewilding] depends on your aims, but also on your philosophy. What are the human goals which we project onto nature?”

It’s a debate that goes to the very heart of rewilding, the nature restoration movement that has swept across the world in recent decades. Perhaps nothing illustrates the line that divides these two perspectives more than what happened at Oostvaardersplassen seven years ago.

Geese and grazers

The Oostvaardersplassen was created back in 1968 when an inland sea was drained to build two new cities, Lelystad and Almere, in the Netherlands’ youngest province, Flevoland. The initial plan was to use the remaining land for industrial development.

But not long after the creation of Flevoland, the swampy part of the Oostvaardersplassen became an important site for greylag geese. The migratory birds would feed on the reedbeds in the marsh during the moulting season in May and June, when they shed and regrew their flight feathers.

The geese played an important role as ecosystem engineers – they maintained the marsh for other birds by keeping the reed beds open and by creating small pools of clear water which supported a diverse array of aquatic species, says Frank Berendse, a retired professor in nature management at Wageningen University in the Netherlands and an early advocate for nature restoration at the Oostvaardersplassen.

“The area was a paradise for marsh birds,” Berendse recalls. The rich marshy ecosystem was a fertile breeding ground for many different birds including the little bittern, little egret and spoonbill. “It was one of the most beautiful birding areas in the Netherlands, and in Europe, during that period,” says Berendse.

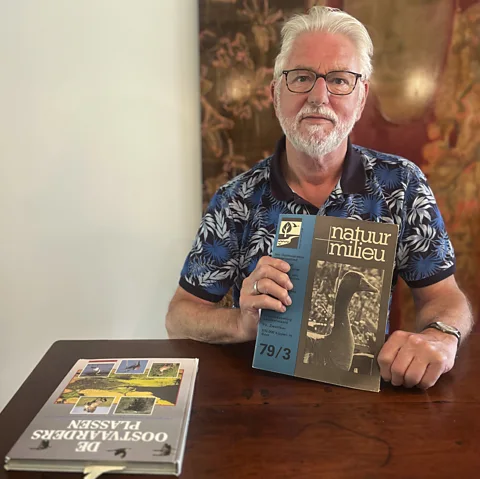

In 1979, Dutch biologist Frans Vera, who had been a PhD student of Berendse’s, wrote an article titled The Oostvaardersplassen: a unique ecological experiment in which he argued that the area had become one of the most important areas for European marsh and waterbird populations.

“It was unbelievable – a treasure trove. But nobody was calling for it to be protected, because so much [nature] had already been lost in the Netherlands,” says Vera.

Vera called for the area to be designated as a nature reserve, and soon became the leader of a movement pushing for this. In 1983, the Oostvaardersplassen was at last designated a nature reserve, spanning 56 sq km (23 sq miles), roughly the size of Manhattan. The reserve now consists of marshland and wet and dry grasslands and is managed by the Dutch national forest service.

By the early 1990s, the number of greylag geese visiting the Oostvaardersplassen totalled 60,000, making it the most important moulting site for the birds in Europe.

Before and after the moulting season, the geese would fatten up by feeding on the grassland, making it vital to keep the landscape open. But vegetation was quickly encroaching and there were concerns that, without intervention, the area would turn into a dense forest, Vera says.

To prevent this from happening, Vera, who by now was working for the national forest service, suggested introducing large herbivores and creating a palaeolithic wood-pasture landscape.

Vera believed that before people started farming in prehistoric times, Europe was not covered by closed-canopy forest – the prevailing view at the time – but rather by “dynamic pasture woodland”. In a paper, he argued that before humans altered the land, the grazing of tarpan and aurochs (the wild ancestors of domestic horses and cows) created grassland and stopped trees from covering the entire continent.

Vera proposed introducing analogues to prehistoric grazers to the Oostvaardersplassen to recreate this grassland in a varied landscape.

“If we wanted to maintain the marshland, we had to preserve the habitat of the greylag geese,” Vera says.

To keep the landscape open and maintain the grassland for the geese, the traditional view was that cows were needed, he says. “Everyone said that if you want to have cows, you need to have farmers,” he says. “That led me to an idea: if domesticated cows can maintain pasture, then surely wild cows could do the same? ‘No!’ cried the entire scientific community. ‘Then it will turn into a forest’. To which I replied: ‘Ok, let’s test that theory.'”

In 1983, Vera introduced 32 German Heck cattle (originally bred in the 1920s by two German brothers who were attempting to revive the extinct aurochs). A year later, he brought over 18 Konik horses from Poland. In 1994, 44 red deer were let loose.

Vera’s idea was to limit human intervention in the landscape; that nature would take care of itself. “It worked,” he says: the landscape stayed open and there were “beautiful reedbeds” for the geese. “The population of grazers grew quickly and there was a huge bird population.”

In other nature reserves, animal populations were kept in check (and regularly shot). But the ethos at the Oostvaardersplassen was to not intervene at all and only shoot the animals if it was clear that they wouldn’t survive the winter. The animals at the Oostvaardersplassen were never given additional feed and were free to roam across the grassland but were unable to move beyond due to fences surrounding the reserve. The ecological goal was to allow natural processes, such as starvation and competition, to shape the landscape, rather than maintain it by human intervention.

The German magazine Der Spiegel called the Dutch nature reserve: “The Serengeti behind the dikes”.

The Oostvaardersplassen was a big wake-up call and the start of a new movement – Frans Schepers

The restoration work at the Oostvaardersplassen was “very innovative,” says Frans Schepers, executive director of the non-profit Rewilding Europe, at a time when there was “very little innovation in conservation” in Europe. “It was all about species and habitats and fixing places, not about processes,” he says. “The Oostvaardersplassen was a big wake-up call and the start of a new movement.”

In 2010, the Oostvaardersplassen was added to the European Union’s Natura 2000 conservation network as an important habitat for marsh birds. Its unique approach to conservation was celebrated in the 2013 documentary The New Wilderness.

Boom and bust

But at the same time, a crisis was brewing that would end up testing the limits of this new approach to nature conservation.

Between 2005 and 2015 grazer populations at the Oostvaardersplassen exploded, decimating the vegetation. “The landscape, which originally was an oasis of elders, hawthorns, willows, thistles and grasses, turned into one giant grassland,” says Berendse.

Due to the rapidly increasing geese population, the grazing pressure in the marsh grew very high, which had a negative impact on the biodiversity and the birdlife residing there, says Berendse. This led to the extinction of a number of rare bird species from the area, including the little bittern and the little egret, he says.

Research carried out by Berendse and other ecologists in 2020 found that 22 rare bird species disappeared from the dry parts of the Oostvaardersplassen between 1997 and 2016.

Berendse says he originally supported Vera’s work but changed his mind after witnessing the negative impact on the area’s birdlife. The explosive growth among the grazers led to “an enormous food shortage” and many starving animals that had to be shot, he says. A total of 1,613 grazers died between December 2015 and April 2016, with rangers shooting 90% of the animals.

Then, during the extremely cold, wet winter of 2018, a “mass mortality event” occurred. Grazer populations fell by around 3,000 (from a previous total of 5,230 in October 2017). The majority of the animals were shot because they were starving.

The dead animals were clearly visible to train commuters passing by the reserve. Photos of the emaciated animal corpses quickly went viral on social media and sparked huge public outrage. People came to the Oostvaardersplassen to drop off bales of hay for the animals and rangers working on the nature reserve received death threats and were accused of animal abuse.

“I received many death threats,” says Vera. “They even threatened my family. It was absolutely terrible,” he says, adding that most of the threats came from hunters and farmers.

He describes the criticism he received from farmers as “hypocritical”. “What is ethical about agriculture? In the Oostvaardersplassen the calves stay with their mother. On the farm, they are taken away after one day. The latter is normal, the former is considered abnormal,” he says.

Mass death

The “mass death” that occurred during the winter of 2017-18 was not unexpected, says Vera. “It’s part of nature. During the previous year the number of deaths was almost zero. So you can say that it’s a kind of natural correction.”

Mass mortality events due to starvation are common in the wild, Vera notes. One study, for example, found that undernutrition was the main cause of mortality (in 75% of cases) among migratory wildebeest in the Serengeti between 1958-98.

“This happens naturally in wild populations,” says Jens-Christian Svenning, a Danish ecologist and professor at the department of biology at Aarhus University in Denmark. “The mortality of wildebeest in the Serengeti can be up to 60% from starvation and no one says they should somehow be managed or culled.”

In Yellowstone in the US, stress and starvation during the winter months is a common cause of bison deaths, Svenning adds. “Very few of them are killed by wolves and it’s not controversial.”

But others such as Berendse say that a direct comparison can’t be drawn between the Oostvaardersplassen and wild landscapes where grazers roam freely, such as the savannah in east Africa, the pampas in South America or the Mongolian steppe. “In those cases, we’re talking about thousands of square kilometres,” says Berendse. “The Oostvaardersplassen is a small area and it is surrounded by fences.”

Its geographical isolation and lack of connectivity to other habitats is a limitation, says Schepers. “[The reserve] would benefit from wildlife corridors and connectivity with other landscapes, because then the animals could move around,” he says. “The Konik horses could then, for example, migrate to other forests in the winter where there is more food and shelter available.”

The lack of predators, such as wolves, is another problem, according to Schepers.

Wolves returned to the Netherlands in 2019 after 150 years, arriving from Germany. There are currently 13 wolf packs found across the country, with 45 pups born so far this year. Wolves in the Netherlands typically feed on wild boar and red and roe deer, but have also preyed on free-roaming cattle used for nature conservation, according to a 2023 study by researchers at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

Wolves have settled in nearby areas such as the Veluwe and “it seems only a matter of time before they find the Oostvaardersplassen”, says Schepers.

This would not only reduce the number of grazers, but create a completely different behaviour, says Schepers. “It would create what we call an ‘ecology of fear’,” he says. “The grazers would split into groups and move around much more and because of that the vegetation would change, as they are not standing in one place and eating everything. It would also have an impact on the energy balance so there would be less reproduction and perhaps a lot of the offspring would be eaten.”

There are no plans to introduce wolves at Oostvaardersplassen though, according to Kuypers. “If the wolf comes, it will be via the natural route,” he says.

Shaped by humans

Following the protests, the authorities of the province Flevoland issued a report in April 2018, requested a change in management and ordered that grazing animals at the Oostvaardersplassen should be fed.

“Nothing is left of the ecological processes and goals underpinning the Oostvaardersplassen,” says Vera.

Rewilding depends on your aims, but also on your philosophy. What are the human goals which we project onto nature? – Hans-Erik Kuypers

The animals at the reserve are now monitored closely and are given an average body condition score, with one being extremely thin and five very well-nourished, Kuypers explains. If their average score approaches two, the animals are fed. Since 2018, not a single animal at the Oostvaardersplassen has died of starvation, according to Kuypers.

In their report, the Flevoland authorities also ruled that large herbivore numbers should be capped at 1,500 annually to stop winter fatalities. In order to keep overall numbers in check, every year animals are moved to new areas or shot (and either sold as meat or sent for destruction), says Kuypers.

The rangers now also manage the landscape by modifying how much water enters the different habitats. They are currently carrying out a “marshland reset”, which involves lowering the water levels in the western part of the marsh to give the reedbeds more room to grow and encourage birds to return to the area.

They have planted young trees, surrounded by small fences to keep them out of the grazers’ reach, and created small pools in the grassland area where herons and wading birds gather.

“There is human intervention, but it’s not a total paradigm shift,” says Kuypers. “This is a landscape shaped by humans, where we have created space for natural processes.”

The annual cap on herbivore numbers is “super unnatural”, says Svenning. A fixed population is “not how ecosystems work naturally”, he says, adding that it hinders the positive ecosystem services that grazers can provide, including natural erosion and breaking up vegetation.

“If you monitor the system you can see those [mass death] years coming, and be proactive before it happens,” Svenning argues. “You can make sure that population numbers are fluctuating, without getting into any kind of real welfare problems.”

From an evolutionary perspective, Svenning says that it is also important to “not remove the natural forces that impact evolution, otherwise, eventually the [herbivores] will degrade to something that can only be a domestic animal”. If wild horses had evolved with “plenty of food, without any stress or predation, they wouldn’t have had such long legs, they would have been some other kind of slower, plumper animal,” he says.

“Scientifically I think it’s a missed opportunity to not allow things to keep going with as little interference as possible,” adds Svenning. “We learn from experiments.”

A tamer view

But Schepers argues that pragmatism is also important when it comes to rewilding. “There are limitations such as the physical landscape, the infrastructure and climate, but there is also the social element,” he says. “You have to find a way for people to accept the idea.”

Berendse says he initially thought it was a good idea to allow nature to take its own course in the reserve. “But it has to be socially acceptable,” he says, noting Vera’s work “led to huge consternation and came at the expense of public support for nature conservation”.

The entire frame of reference for domesticated animals was projected onto these wild animals – Frans Vera

Vera believes the anger from protesters was partly driven by the fact that the herbivores at the Oostvaardersplassen were never seen as wild animals. “The entire frame of reference for domesticated animals was projected onto these wild animals,” he says. “[The view that] horses are for riding, cows are for milking.”

Schepers agrees that this is a challenge for rewilding projects such as the Oostvaardersplassen. “We grow up with domesticated cows and horses and a lot of people cannot make that mind shift and go ‘Ok, this is a wild animal,'” he says.

Despite the controversy surrounding his work, Vera’s vision for nature was hugely influential and helped shape other rewilding initiatives across Europe, including at Knepp Estate in West Sussex, UK, where deer, pigs, Exmoor ponies and hardy cattle now roam freely. (Read about how wild storks are breeding in Britain for the first time in 600 years at Knepp).

At Knepp Estate, which in 2001 became the UK’s first major lowland rewilding project, the animals roam in natural herds in a wood pasture landscape, maintaining the ecosystem by grazing, browsing, rootling, rubbing and trampling, spreading nutrients as they go.

“The Dutch were so blue-sky thinking to come up with a programme like the Oostvaardersplassen,” says Charlie Burrell, the co-owner of Knepp Estate who started the project alongside his wife Isabella Tree. “The idea that we could just let nature rip and see how that looked was very exciting and very interesting.”

Inspired by Vera’s work at the Oostvaardersplassen, Burrell and Tree decided to introduce “proxy grazing and browsing animals to drive new habitats for the future” on 3,500 acres (1,400 hectares) of former farmland, Burrell says.

But unlike at the Oostvaardersplassen, the herbivore populations at Knepp were kept in check from the start. In fact, the whole premise of Knepp is to demonstrate a way of producing meat more in line with nature restoration: animals are shot and processed for meat, with the estate selling 75 tonnes of free-roaming, pasture-fed organic meat in its shop and restaurant every year.

“I think the boom-and-bust cycle, without large predators and without an African scenario, becomes difficult for people to understand,” says Burrell, referring to Vera’s vision for the Oostvaardersplassen. “We’re killing our cattle, ponies, pigs and deer and eating them and people seem to have far fewer objections to that model.”

Although Knepp took a different approach, Burrell says Vera’s work at the Oostvaardersplassen was “a very brave thing to have done and we have learned a lot from it”. Knepp Estate even held a conference in 2017 celebrating Frans Vera’s work.

The Oostvaardersplassen has also inspired other rewilding projects across Europe. In Spain’s Iberian Highlands, Rewilding Europe has reintroduced wild horses, tauros and other large grazers to help restore natural processes. “We are seeing more forest fires [in the region] and one of the reasons for this is that areas are not grazed anymore,” says Schepers. This means there is more vegetation which fuels files that “burn like infernos”, he says. The introduced grazers, he says, are helping reduce the wildfire risk in the region.

A radical idea

The now notorious Dutch rewilding project and the public outcry over it undoubtably left a mark on how many people think about conservation and continues to spark fervent debate about how we should manage nature.

“[Vera’s vision] was a very radical idea; that you allow large populations to fluctuate with starvation and flush periods,” says Burrell. “It [inspired] a real bubbling ferment of discussion, agreement and disagreement.”

Vera also feels the project led to a shift in perspective, and says that “more people now think about nature as a dynamic system where large herbivores are the architects of the landscape”, rather than as a stable landscape. “It certainly planted a seed and had a big impact on nature.”

Vera, says Schepers, was a pioneer and a fighter. “The Oostvaardersplassen led to a real paradigm shift in thinking,” he says. “We no longer saw nature as something that needed to be cured, but rather as an incredible force in itself.”