Military drills spark hundreds of wildfires in UK

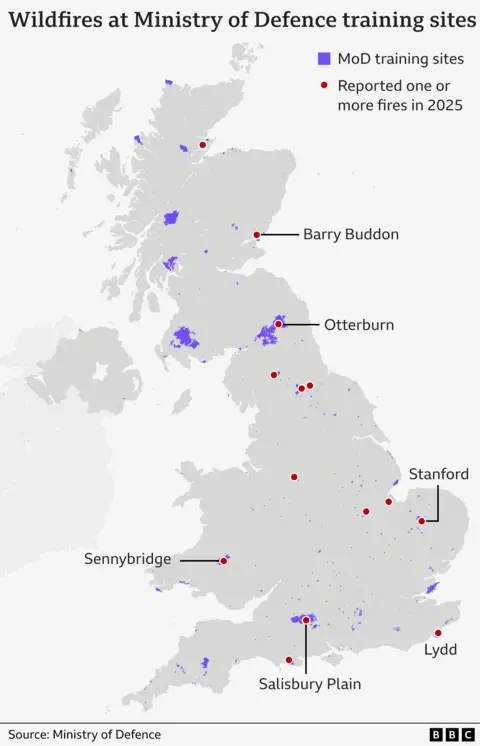

Live-fire military training has sparked hundreds of wildfires across the UK countryside since 2023, with unexploded shells often making it too dangerous to tackle them.

Fire crews battling a vast moorland blaze in North Yorkshire this month have been hampered by exploding bombs and tank shells dating back to training on the moors during the Second World War.

Figures obtained by the BBC show that of the 439 wildfires on Ministry of Defence (MoD) land between January 2023 and last month, 385 were caused by present-day army manoeuvres themselves.

The MoD said it has a robust wildfire policy which monitors risk levels and limits live ammunition use when necessary.

But locals near the sites of recent fires said they felt the MoD needed to do more to prevent them, including completely banning live fire training in the driest months.

Wildfires in the countryside can start for many reasons, including discarded cigarettes, unattended campfires and BBQs and deliberate arson, and the scale of them can be made worse by dry, hot conditions and the amount of vegetation on the land.

But according to data obtained under the Freedom of Information Act, there have been 1,178 wildfires in total linked to present-day MoD training sites since 2020 – with 101 out of 134 wildfires in the first six months of this year caused by military manoeuvres or training.

More than 80 of the fires caused by training itself so far this year have been in so-called “Range Danger Areas” – also known as “impact zones”.

These are areas where the level of danger means the local fire service is usually not allowed access and the fire is left to burn out on its own, albeit contained by firebreaks.

The large amounts of smoke produced can lead to road closures, disruption and health risks to local residents, who are directed to keep their windows shut despite it often being the hottest time of the year.

One villager who lives near the MoD’s training site on Salisbury Plain said wildfires there, like the recent one in May, were “a perennial problem” and the MoD had to do more to control them and restrict the use of live ordnance to outside of the hottest months.

Neil Lockhart, from Great Cheverell, near Devizes in Wiltshire, said the smoke from fires left to burn was a major environmental issue and posed a risk to the health and safety of locals.

“It’s the pollution. If you suffer like I do with asthma, and it’s the height of the summer and you’ve got to keep all your windows closed, then it’s an issue,” explained Mr Lockhart.

Arable farmer Tim Daw, whose land at All Cannings overlooks the MoD training site on Salisbury Plain, said he “must have seen three or four big fires this year” but found the smoke only a “mild annoyance”.

He said many locals were worried about the impact of the wildfires on wildlife and the landscape, saying the extent of the area affected by the blazes often looked “fairly horrendous”, and likened it to a “burnt savannah”.

But he said the MoD was “very proactive” in keeping locals informed about the risks of wildfires and any ongoing problems on their land.

Wartime “legacy”

Aside from the problem of live military training sparking fires, old unexploded ordnance left behind from previous manoeuvres make wildfires harder to fight,

This month has seen a major fire burning on Langdale Moor, in the North York Moors National Park, since Monday, 11 August.

It has seen a number of bombs explode in areas that were once used for military training dating back to the Second World War.

One local landowner, George Winn-Darley, said the peat fire had produced “an enormous cloud of pollution” that could have been prevented if there had not been live ordnance on site.

“If that unexploded ordnance had been cleared up and wasn’t there then this wildfire would have been able to be dealt with, probably completely, nearly two weeks ago,” he said.

Mr Winn-Darley called for the MoD to clear up any major munitions left on the moors.

“That would seem to be the absolute minimum that they should be doing,” he said.

“It seems ridiculous that here we are, 80 years after the end of the Second World War, and we’re still dealing with this legacy.”

A MoD spokesperson said the fire at Langdale had not started on land currently owned by the MoD but that an Army Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) team had responded on four occasions to requests for assistance from North Yorkshire Police.

“Various Second World War-era unexploded ordnance items were discovered as a result of the wildfires, which the EOD operator declared to be inert practice projectiles. They were retrieved for subsequent disposal,” he explained.

He added that the MoD monitors the risk of fires across its training estate throughout the year and restricts the use of ordnance, munitions and explosives when training is taking place during periods of elevated wildfire risk.

“Impact areas” are constructed with fire breaks, such as stone tracks, around them to prevent the wider spread of fire and grazing is used to keep the amount of combustible vegetation down.

Earlier this month, the MoD launched its “Respect the Range” campaign, designed to raise the public’s awareness of the dangers of accessing military land, such as live firing, unexploded ordnance and wildfires.

A spokeswoman for the National Fire Chiefs Council (NFCC) said it worked closely with the MoD to “understand the risk and locations of munitions and to create plans to effectively extinguish fires”.

“We always encourage military colleagues to account for the conditions and the potential for wildfire when considering when to carry out their training,” she added.