In India, war came dressed in feminist camouflage

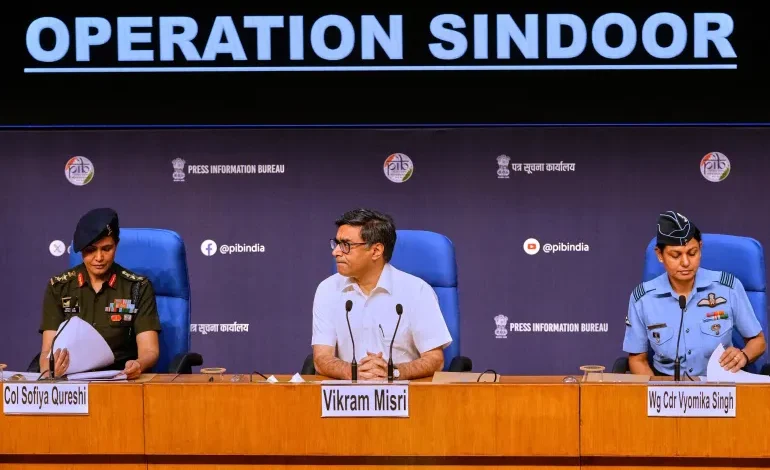

When two female officers of the Indian armed forces – one Hindu, one Muslim – took centre stage to announce Operation Sindoor, the government celebrated it as a landmark moment for gender inclusion. The image of uniformed women addressing the media from the front lines, avenging the deaths of 26 civilians, all men, and symbolically restoring the sindoor (vermilion) of widowhood, was widely praised as feminist iconography in service of the nation.

The moment echoed a historical parallel: during the 1971 Indo-Pak War, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi was famously likened to the Hindu warrior Goddess Durga, a symbol of feminine power and nationalist resolve, in recognition of her decisive role in the creation of Bangladesh. That invocation of Durga underscored how Indian political power is often framed through a gendered and mythologised lens, blending statecraft with religious symbolism.But can women leading war be inherently feminist? Nation-building, as feminist scholars have long warned, is not a gender-neutral project. It reconfigures women into roles that serve its ends: sacrificial mothers, grieving widows, or militant daughters of the nation. Scholars like Nira Yuval-Davis argue that women are positioned as symbolic bearers of the nation’s honour and cultural authenticity but rarely as its political agents. In the Indian context, scholars like Samita Sen and Maitrayee Chaudhuri remind us that women’s public roles have historically been framed not in terms of autonomy, but duty to patriarchal structures. Therefore, the mere presence of women in public or political spheres does not automatically equate to gender justice. Representation must also be interrogated for its objectifying function.Today’s military feminism, in which women gain visibility in war zones, follows this same path: celebrating women’s ability to “be like men” while leaving untouched the masculine and patriarchal foundations of militarism itself. This can be observed in Operation Sindoor, which projects the spectacle of two women in uniform as feminist optics, while the script they perform remains deeply patriarchal, demanding women prove their worth through masculine-coded nationalism.

Such feminist optics align neatly with the ideological framework of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). Founded in 1925, the RSS is a Hindu nationalist organisation that serves as the ideological parent of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). It envisions India as a Hindu rashtra (nation), advocating cultural nationalism rooted in Hindu traditions and values. Scholars like Christophe Jaffrelot argue that the RSS fosters majoritarianism and undermines India’s secular fabric. Its paramilitary structure and emphasis on discipline and nationalism reveal its aim of deepening the hierarchical and patriarchal structure of Indian society.

The women’s auxiliaries of the RSS – the Rashtra Sevika Samiti and Durga Vahini – reflect and reinforce this patriarchal vision. These groups have long trained women in martial arts and ideological devotion not for feminist liberation, but to protect the Hindu rashtra. The aesthetics of Operation Sindoor – its saffron undertones, warrior femininity, and choreographed resolve – mirror this legacy. As Bina D’Costa’s work on gender and war in South Asia underscores, women’s bodies often become vehicles of nationalist redemption. The inclusion of a Muslim officer in this tableau may appear to signal secular pluralism. But as D’Costa warns, such inclusions often serve to legitimise exclusionary frameworks. Her presence sanitises a majoritarian script by casting minority visibility as proof of national unity, even as Islamophobic currents persist in broader public discourse.