Could the UK actually get colder with global warming?

Of all the possible climate futures, there’s a scenario where the United Kingdom and north-west Europe buck the trend of global warming and instead face plunging temperatures and freezing winters.

It’s not the most likely outcome, but a number of scientists fear that the chance of it happening is growing, and that the consequences would be so great that it deserves proper consideration.

They are concerned that the ocean currents that bring warm water from the tropics to the North Atlantic could weaken – or even collapse – in response to climate change.

Huge uncertainties remain about when – or even whether – a collapse could happen. So, how likely is it, and what would it mean?

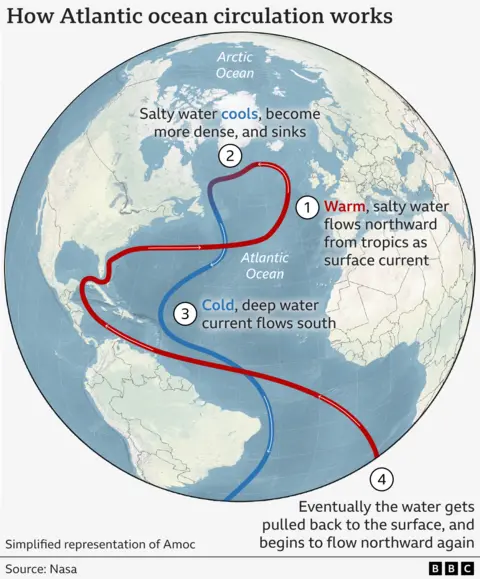

The system of Atlantic currents, called the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (Amoc), is a key reason why the UK is warmer than Moscow, despite being a similar distance from the Equator.

Forming a vital part of our climate system, this conveyor belt distributes energy around the planet, bringing warm, salty water from the tropical Atlantic to cooler regions south of Greenland and Iceland, and also the Nordic Seas.

The warmth from the ocean is transferred to the air above it, helping keep temperatures milder than they otherwise would be.

As this salty water cools, it becomes denser, and sinks, before flowing back towards the southern hemisphere as a deep ocean current. This water eventually gets pulled back up to the surface, and the circulation continues.

But Amoc appears to be getting weaker.

We don’t know for sure, because direct and continuous measurements of Amoc strength have only been taken since 2004. That’s not long enough to be able to identify a definite change.

But indirect evidence suggests it could have already slowed by around 15% over the last couple of centuries, although not all scientists agree.

One indication is the sediments on the ocean floor. Larger grains indicate a stronger current. By measuring the size of the grains and calculating their age, scientists can estimate how much Amoc has slowed over time.

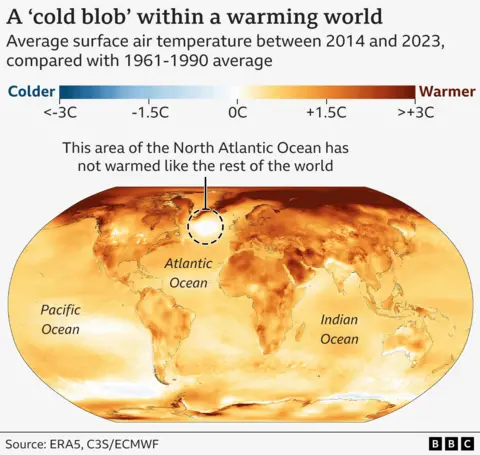

Another piece of evidence is the so-called ‘cold blob’ or ‘warming hole’ in the north Atlantic. This describes a region which appears to have cooled in recent decades, unlike the vast majority of the world.

A slowdown in Amoc – meaning less warmer water would be transported to this region – is seen as a possible culprit.

This is “a very clear signature and footprint of a classic Amoc slowdown” says Matthew England, professor of oceanography at the University of South Wales.

The UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expects Amoc to weaken this century. But the major concern is that Amoc could suddenly “switch off”, as appears to have happened repeatedly in the Earth’s past.

Today, global warming appears to be making the water in the north Atlantic less salty, due to extra freshwater from a melting Greenland ice sheet and more rainfall.

As fresher water doesn’t sink as easily, this is expected to slow the circulation and so bring less saltwater northwards from the tropics.

Beyond a “tipping point”, this loop could lead Amoc to runaway collapse.

“We really want to avoid a tipping point because then there’s nothing we can do about it,” warns David Thornalley, professor of ocean and climate science at University College London.

Where might the tipping point be?

No one really knows how close it may be.

In 2021, the IPCC said it had “medium confidence” that Amoc would not collapse abruptly this century, although it expected it to weaken.

But some more recent studies have pointed to a growing possibility of Amoc passing a tipping point in the coming decades, beyond which full collapse would be inevitable.

Each study comes with various caveats and uncertainties, and different climate models can give different results for a system as complex as Amoc.

“We don’t believe the idea of an Amoc collapse this century has substantially changed because of these new results,” cautions Dr Laura Jackson, oceanographer at the Met Office.

But many scientists are growing increasingly concerned. Prof Thornalley argues that, whatever the imperfections of individual studies, taken together they “lead to a conclusion that we maybe need to be worried”.

Following the new evidence, more than 40 leading ocean and climate scientists signed an open letter last October calling for wider recognition of the “greatly underestimated” risks.

That is not to say the signatories believe Amoc will pass a tipping point this century. But they warn it is now enough of a possibility to warrant proper consideration.

“I’d say you’re looking at a risk of reaching a tipping point in the coming decades that could be at the 10 or 20% level even if we hold the line at 2C warming [above temperatures of the late 19th Century, before humans started significantly warming the climate],” warns Tim Lenton, professor of Earth system science at the University of Exeter.

Given the magnitude of the consequences from Amoc collapse, these probabilities “are not trivial,” he adds.

What would happen if Amoc collapsed?

Even the most likely scenario – where Amoc continues to weaken this century – could have serious effects.

“If the Amoc gradually weakens over the next century, you’re going to get global warming but less warming over Europe,” says Dr Jackson.

That would still mean the UK getting hotter summers with climate change, but a weaker Amoc could also fuel more winter storms as regional temperature patterns change.

A full-scale collapse, meanwhile, would be “like a war situation […] something almost unimaginable,” says Prof Lenton.

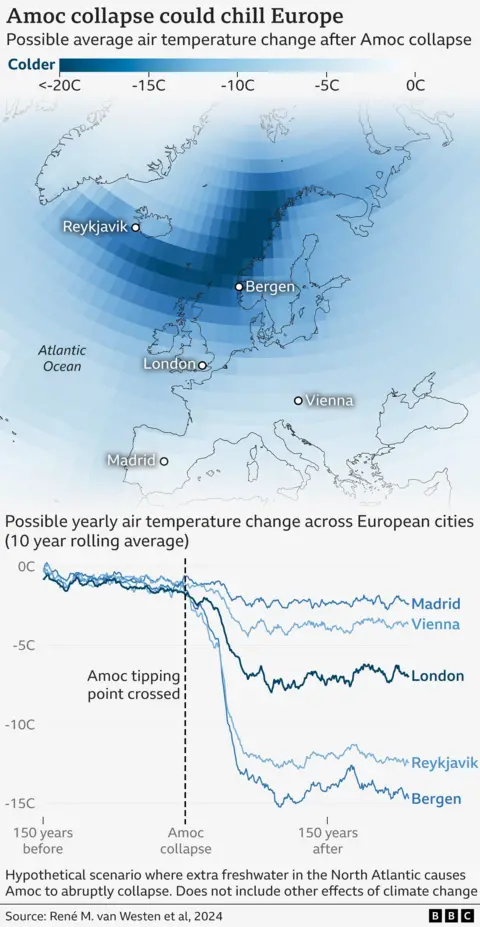

While it could take a century or more for impacts to play out, temperatures in northern Europe could fall by a couple of degrees a decade.

In the UK, it could “become horribly, horribly cold … like living in northern Norway,” Prof Thornalley warns.

“Our infrastructure is not set up for that.”

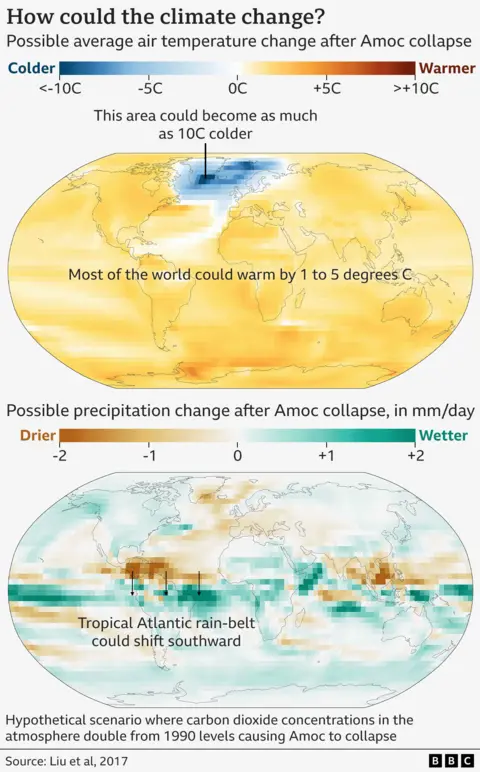

There could be global consequences too, such as shifts to the tropical rain belts.

“That’s a big story,” warns Prof Lenton.

“If you lost the monsoon or seriously disrupted it, you’d have humanitarian catastrophes, in simple terms, in west Africa [and] probably in India.”

How we prepare for this alternative future poses challenges for governments.

Prof Lenton draws parallels with preparations for the Covid-19 pandemic – another major event which scientists had warned about, but had no way of knowing when it might occur.

But a recent report warned the UK has a “glaring national security blind spot for climate threats” such as those posed by Amoc collapse. The government admitted last year that it “has not assessed the effect of any [Amoc] slowing or collapse” on economic planning.

Scientists are clear that the fundamental way to reduce these risks is to cut the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change.

“We’re playing a bit of a Russian roulette game,” warns Prof England.

“The more we stack up the atmosphere with greenhouse gases, the more we warm the system, the more chance we have of an Amoc slowdown and collapse.

“And so I think people need to not give up, because there’s so much to be gained by reducing emissions.

“The scale of change is just so much worse if we do nothing.”