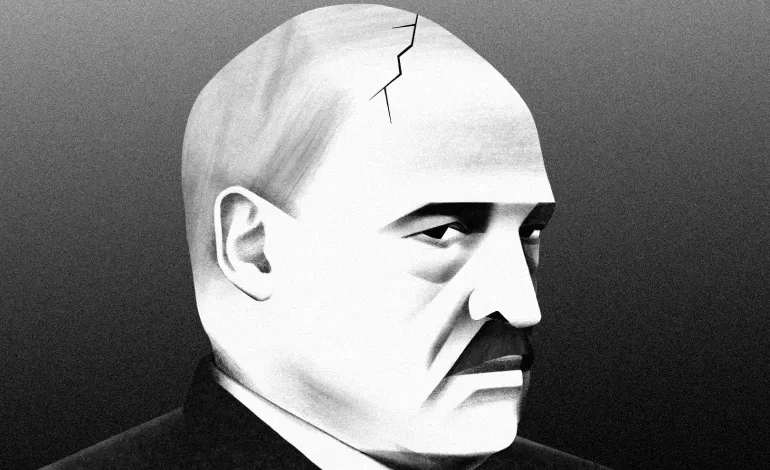

Lukashenko: Before 2025 election, ‘still afraid of the people’

On January 26, Belarusians will cast their ballots in a presidential vote. Officially, there are five candidates, but 70-year-old Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko, who has ruled the country for more than three decades, will almost certainly retain his seat.

While Vladimir Putin’s Russia tolerated a degree of open dissent, at least until the invasion of Ukraine, Lukashenko was described for many years as “Europe’s last dictator” – a reputation which didn’t seem to faze him.

“I am the last and only dictator in Europe. Indeed, there are none anywhere else in the world,” he told Reuters in 2012.

Belarus’s opposition, the United States, the European Parliament and rights groups have dismissed the upcoming vote as a “sham”. The last presidential elections in 2020 kicked off mass protests amid widespread allegations of vote rigging, followed by a brutal crackdown by the authorities.

Experts and insiders say Lukashenko is driven by a “thirst for power” and, having been shaken by those demonstrations, the fear of losing control.

“This desire for power has been driving him for 30 years. It does not let him relax for a second,” Valery Karbalevich, a political observer at Radio Liberty and author of an unofficial biography of Lukashenko, told Al Jazeera. “Power and life are the same thing … and he does not imagine his life without power.”

Born in 1954 in the town of Kopys in northern Belarus, Lukashenko, a self-confessed troublemaker at school, was a Soviet pig farm manager before becoming president. The leader, who at times has made outlandish claims such as vodka and visits to the sauna being able to prevent COVID, is ruthless and distrustful, observers and those who worked under him say.

“This man is capable of giving an order to kill if someone goes against him,” said Pavel Latushka, Belarus’s now-exiled former minister of culture from 2009 to 2012.

“I had a conversation with him where he told me directly: ‘If you betray me, I will strangle you with my own hands.’ He later repeated this publicly in a recent [2024] interview with Russian propagandist Vladimir Solovyov.”

As Belarus heads to the polls on Sunday, who is the man behind the leader and what motivates him today?

Soviet nostalgia

Belarus, a landlocked nation of a little more than nine million bordering Russia, Ukraine, Poland, Latvia and Lithuania, was once part of the USSR. Like many leaders of former Soviet republics, Lukashenko’s political career began during that period. Unlike them, however, Lukashenko did not embrace nationalism and was the only lawmaker in Soviet Belarus to vote against his country’s independence in 1991.

Nostalgia for the Soviet era is reflected in much of Lukashenko’s governance.

“He lived in the Soviet Union for more than 30 years and now, he cannot go beyond that life experience,” said Karbalevich.

Lukashenko, then 39, won Belarus’s first, and so far only, presidential election deemed free and fair by outside observers in 1994. The independent candidate ran on a populist platform, pledging to root out corruption and railing against the “lawlessness” which he said held the country “hostage”. Immediately post-independence, Belarus suffered from a stagnating economy, corruption, inflation and racketeering gangs.

While it is difficult to pinpoint when exactly Lukashenko developed distrustful tendencies, or whether he always had them, he survived an assassination attempt on the campaign trail when his car came under fire by unknown assailants. A state television documentary later claimed the attackers were working on behalf of high-ranking officials.

Lukashenko won approximately 80 percent of the vote, defeating the country’s first prime minister, Vyacheslav Kebich, who inherited the job after independence and under whom quality of life had deteriorated.

Within a year of assuming office, Lukashenko held a referendum that changed Belarus’s white-and-red flag to one closely resembling the old Soviet design. He told World War II veterans, “We have returned to you the national flag of the country for which you fought.”

He maintained a planned economy, with state monopolies over industry and kept the collective farms open, winning the loyalty of the agricultural sector. This state-run economy prevented the emergence of powerful oligarchs dominating national politics, unlike in Russia and Ukraine, although a handful of businessmen with links to the government have prospered in recent years.

“At the beginning of his presidency, he was really popular,” explained Karbalevich.