Bowie’s Berlin: Up against the wall

When David Bowie’s Glass Spider Tour arrived in West Berlin on June 6, 1987, the city was the world’s de facto capital of geopolitical turmoil, cleft in two physically and politically by 168km (104 miles) of machine-gun-guarded concrete wall.

The stage on which Bowie was to perform lay to the west of the division line on the derelict lawn of West Berlin’s Platz der Republik, a grassy square in front of the imperious Reichstag building. The building had once been the seat of the German government (and is again today) but in the late 1980s had stood largely unused since World War II due to its proximity to the Berlin Wall looming directly behind it.

The tour had come to participate in the Concert for Berlin, an event held as part of the city’s 750th-anniversary celebrations, and when the performance venue was erected, its West Berliner organisers made sure that several speakers were pointing directly at the Wall.

It was a cool evening when Bowie and company took to the stage beneath a 15-meter (50-foot), illuminated spider before an audience of some 80,000 fans. At the same time, listeners from the east gathered as close as they dared, their numbers accumulating steadily.

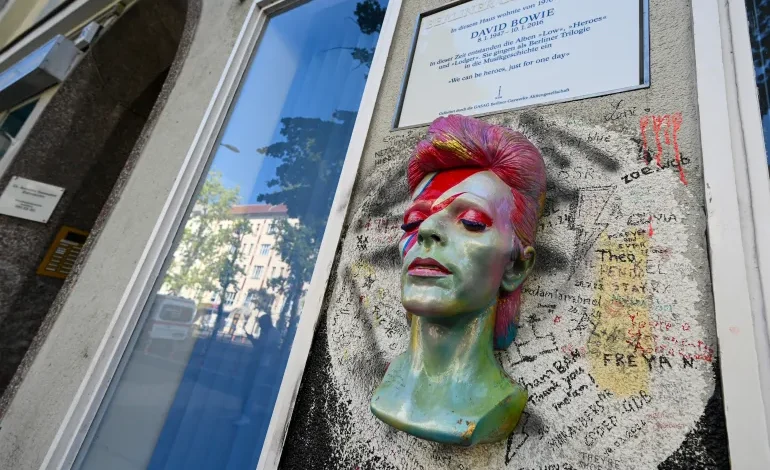

Attendees to the west got their money’s worth, as Bowie rocked through a lengthy 24-song set followed by three encores. The tracks were largely drawn from his latest run of albums – Scary Monsters, Let’s Dance and Never Let Me Down – but a few harkened back to those he’d recorded a decade earlier while living in the city, most notably his anti-Wall anthem, “Heroes”.

By all accounts the performance was well-received by those watching from the Reichstag. Bowie himself later expressed that it was an emotional experience.

For those listening to the east, however, the music may have been welcome, but the atmosphere was oppressive as members of the Volkspolizei – the People’s Police, a civilian wing of the much-feared Stasi secret police – spent the duration of the concert hassling and intimidating those who had congregated to hear it.

The following evening as the crowd swelled precipitously for a second day of music, violence erupted when East German authorities cracked down on eastern listeners – a repressive act that only inflamed opposition and ultimately contributed to the Wall’s collapse.

A tale of two cities

At the time, Berlin sat at the crux of the Cold War. In the wake of World War II, the victorious powers had chopped Germany into four regions, each occupied and administered by one of the United States, the USSR, the United Kingdom and France. But with Berlin situated deep inside the Soviet zone, it was agreed that the capital, too, would be divided along similar lines.Then in 1961, following years of rising tension, the Soviets boxed in the western Allied section of the city with a heavily fortified and guarded barrier – the infamous Berlin Wall – which divided families and severed economic and social ties.

“It’s hard for any of us to really imagine,” says Berlin Wall historian Hope M Harrison, professor of history and international affairs at George Washington University. “This was a world metropolis like New York, London, Paris, Rome – and suddenly to have it divided in two!” Families were separated, employees cut off from their jobs, students from school. “It had a huge, devastating impact on the people of Berlin.

“For Berlin, it was a gash through the city,” Harrison explains. “For the world, it symbolised two things: the Cold War – here it is in concrete – but also both the brutality and simultaneously the weakness of the Communist regime.” That the powers that lay to the east felt it necessary to wall its people in was “a kind of admission of defeat”, she added.

Life on both sides of the barrier became increasingly grim. Those to the east experienced pervasive censorship and a rapid diminishing of material standards due to the food and supply shortages that plagued the Soviet Union. Those in West Berlin settled into their besieged enclave, where greater cultural freedom allowed for wide-ranging artistic experimentation, but the sense that it was all teetering on the brink persisted.

“West Berlin very much became a countercultural place,” says Harrison, gravitating artists, punks, anarchists, and East Germans looking to escape compulsory military service. “It was living on the edge, so it attracted people who were happy to live on the edge, some of them with the Berlin Wall literally in their back yard or across the street.”