Why is Hungary’s Orban sending soldiers to Chad?

In hot N’Djamena, an unlikely new language – Hungarian – is flowing alongside the usual mix of Arabic and French, signalling the presence of diplomats from Chad’s new international partner.

In the past year alone, Hungary has opened a diplomatic mission in the Sahelian nation, launched a humanitarian centre and promised $200m in aid. It also plans to send soldiers to help Chad fight armed groups.

The aid is a generous gesture from a Central European country that has had no substantive relations with Chad previously – but it’s also an eyebrow-raising one, experts said.

Hungary is one of Europe’s poorer countries, and it presently has zero economic holdings in Chad or the Sahel. There are also no Hungarian communities there.

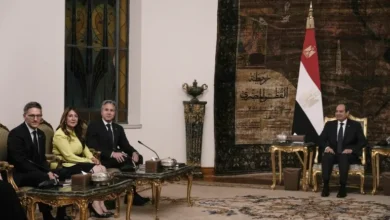

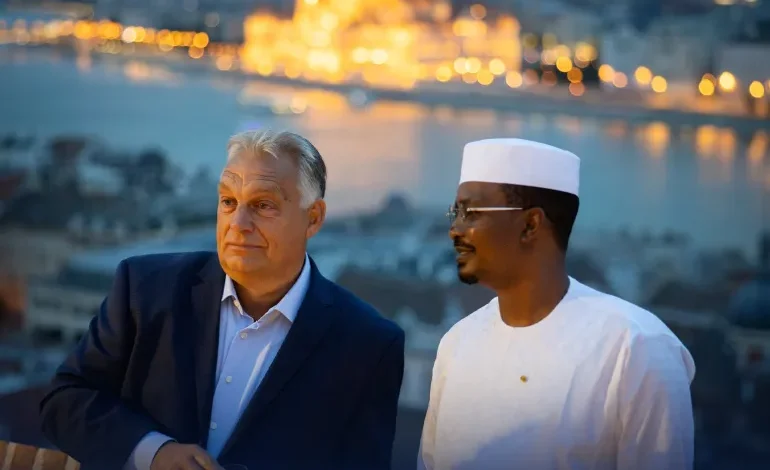

However, Prime Minister Viktor Orban has stressed the need for Europe to befriend countries in the Sahel, where, he said, a toxic mix of armed groups and military governments is fuelling migration.“Migration from Africa to Europe cannot be stopped without the countries of the Sahel region. … That is why Hungary is building a cooperation partnership with Chad,” Orban said in September.

Poverty and armed groups

Officials in Budapest said the newly built humanitarian centre in N’Djamena will help coordinate 150 million to 200 million euros ($162m to $216m) in humanitarian aid, which will target the arid country’s agriculture and education sectors and help boost digitalisation. An additional 1 million euros ($1.08m) from the state aid agency, Hungary Helps, will go to funding healthcare.

Orban’s government said the point is to respond locally to development issues, including poverty and inadequate healthcare, before people are prompted to seek better lives in Europe.

Chad is one of Africa’s poorest countries. Forty-two percent of its 20 million people live on less than $2.15 a day, according to the World Food Programme. Disrupted trade with its war-torn neighbour Sudan has driven food prices up, putting further pressure on the economy. Besides that, it has taken in 1.2 million people fleeing conflict in Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR). Hungary’s argument: If Chad is destabilised, it could open a “floodgate” of people to Europe.

Last month, Chadian President Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno touched down at Budapest’s airport, decked out in his signature white, flowing jilbab for a two-day state visit to Hungary. There, Deby and Orban finalised the terms of the humanitarian package, marking Hungary’s first aid treaty with an African nation.

Orban also announced 200 Hungarian soldiers will deploy to Chad to train local forces against armed groups. Chad faces multiple threats from groups that want to unseat Deby, from CAR rebel groups that operate on Chad’s southern border to Boko Haram, whose fighters have settled along Lake Chad bordering Nigeria.

It’s unclear when the forces will be deployed and if they will play an active or supportive role. The Chadian National Assembly would have to approve the move, but this has not happened yet, and there’s no clear timeline as to when legislators will take a vote.

In the Hungarian National Assembly, which is controlled by Orban’s ruling coalition of his Fidesz party and the Christian Democratic People’s Party, legislators approved the security agreement when it was first presented in November 2023 in a 140-30 vote.

In addition to the military deployment, Hungary said it has “initiated” the transfer of an additional 14 million euros ($15m) of its contributions to the European Peace Facility (EPF) to Chad.

The EPF, formed in 2021, allows European Union members to pool contributions and jointly deliver military aid to partner countries. Much of the funding has gone to Ukraine although Orban – an ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who is waging a war in Ukraine – has repeatedly frustrated other EU members’ efforts to send more funds to Kyiv.

Hungary in September formally asked other EU members to approve its transfers to Chad. There’s no explicit approval from the bloc yet, but at the time, Orban said Hungary expected other members to be on board.

‘Confluence of stability and conflict’

During Deby’s September visit, Orban said the point of the development and military cooperation with Chad was to stop migration from Africa, a phenomenon that many European countries see as a threat amid surging migration levels in recent years.

“It felt like a bit of a random choice, but in retrospect, it actually makes sense,” said Beverly Ochieng, an analyst with Control Risks, an intelligence firm based in the United Kingdom.

“Chad has one of the strongest armies in the region,” she told Al Jazeera. “Despite the threats it faces, though, the government maintains strong stability and a strong buy-in with the military there.”

In the past decade, the Sahel region – the band of land that lies below the Sahara – has faced rising levels of violence from armed groups and as a result, emigration. In Mali and Burkina Faso in the western Sahel, armed groups are taking over swaths of land while Niger also faces mounting threats. Although militaries there seized power in coups and expelled foreign forces – including French, American and EU troops – they’ve largely failed on their promises to restore peace.