Japan’s ruling party faces ‘generational battle’ as it chooses new leader

Given that most Japanese prime ministers have survived only a year or two in the job, Kishida’s three-year term remains the eighth longest in Japan’s post-war history.

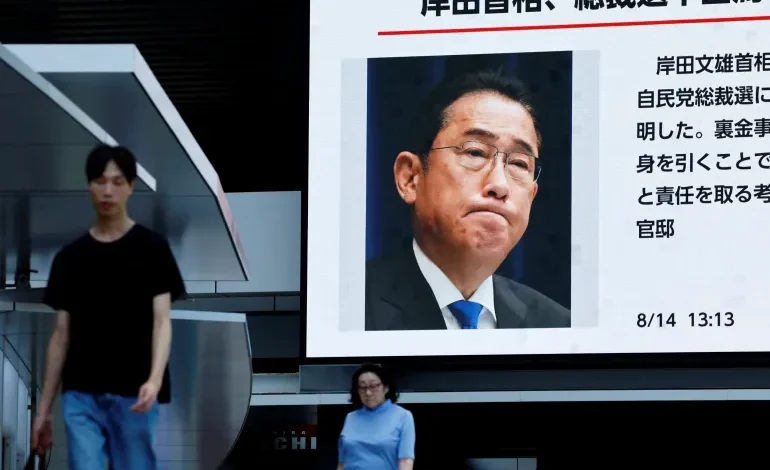

But marred by controversy, he said stepping aside was a chance for a reset.

“I made this heavy decision thinking of the public, with the strong will to push political reform forward,” he told reporters on August 14.

The extent of that reform will become visible next month, as the LDP elects its next leader. Beyond deciding Japan’s next prime minister, the outcome of the leadership race looks set to define the direction of the governing party and Japanese politics for years to come.

Kishida said it was important for the party to have “transparent and open elections and free and vigorous debate” in the contest to “show the people that the LDP is changing and the party is a new LDP”.

For much of the past year, the party has been embroiled in a corruption scandal – in which members of one of its powerful factions were accused of failing to declare campaign money – that has undermined the LDP’s traditional power structures.

The scandal has also fuelled a desire for change, priming September’s leadership race as a contest between the old guard and a younger generation, according to Rintaro Nishimura, an associate in the Japan practice at the Asia Group, a Washington-based strategic advisory firm.

“There’s a desire within the party to see a fresh face. Not just in the sense that they need someone new at the top of the ticket, but someone who can really show the public that the LDP is changing,” he told Al Jazeera.

Strife at home

Kishida was elected for a three-year term as LDP president in September 2021, before winning a general election one month later.

The 67-year-old enjoyed success on the international stage during his tenure, improving relations with South Korea, forging closer links with NATO, and deepening United States-Japanese ties amid China’s increasingly bellicose stance on Taiwan, a democratically ruled island claimed by Beijing.

In 2022, Kishida instructed his cabinet ministers to increase Japan’s defence budget to 2 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP) beginning in 2027. He also responded decisively to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that year, imposing sanctions on Moscow, providing security assistance to Ukraine and inviting Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy to the 2023 G7 summit in Hiroshima.

In April, Kishida signed more than 70 defence pacts with Washington, a move US President Joe Biden described as the “most significant upgrade in our alliance since it was first established”.

But for all of Kishida’s achievements abroad, domestic politics has proved far more challenging.

The LDP was first rocked in the wake of the assassination of Shinzo Abe in July 2022, when it emerged that Abe’s killer had targeted Japan’s former prime minister over his ties to the Unification Church. The man blamed the organisation for bankrupting his family, claiming it coerced his mother into making excessive donations.

The church is thought to raise about 10 billion yen (about $69m) a year in Japan and has faced accusations of being a cult and financially exploiting its purported 100,000 members.

Abe’s assassination exposed the scale of the religious movement’s relationship with several top LDP politicians. In October 2023, Kishida requested a court order revoking the church’s legal status and tax exemption, also telling party members to cut ties with the movement and offering legal redress to its victims.

But public trust was eroded further when, in November 2023, it emerged that members of a powerful conservative faction in the LDP once led by Abe had failed to report more than 600 million yen (about $4.15m) in campaign money, storing it in illegal slush funds.

Ten LDP lawmakers and their aides were indicted in January, accused of violating Japan’s Political Funds Control Law. In June, Kishida pushed through amendments to the law, lowering the threshold for sums that must be declared in a crackdown on political donations.

Critics, however, said he did not go far enough and left loopholes that could be exploited.

“Kishida was hit with two scandals that converged during the three years he was prime minister,” Nishimura said. “He was unable to deal with these two problems properly and so that ended up destroying his political longevity.”

Political factions, the grouping of lawmakers in political, voting, and funding blocks, were also seen to be at the heart of the slush fund scandal. A mainstay of the LDP and Japanese politics more broadly, factions have also faced accusations of being opaque and unaccountable.

“Factions functioned as parties within parties,“ Mikitaka Masuyama, a political science professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, told Al Jazeera. “But after the scandal, many people said the factions are bad. They said they are the reason why we had this money scandal and called for the factions to be abolished.”