India election results: Did ‘secular’ parties let Muslims down too?

As Indian opposition leader Rahul Gandhi addressed journalists after election results demonstrated a dramatic setback for Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), he held up a pocket-sized version of India’s Constitution.

“It was a fight to save the constitution. I would like to thank everybody who has participated in this election. I am proud of the people who resisted the onslaught on this constitution,” Gandhi said on Tuesday evening.

“It’s the poor and marginalised people who came out to save the constitution. Workers, farmers, Dalits, adivasis [Indigenous] and backwards have helped saved this constitution.

“This constitution is the voice of the people. We stand with you and fulfil the promises.”

Missing from the list of people Gandhi thanked were India’s 200 million Muslims, the country’s largest religious minority. Muslims are believed to have overwhelmingly voted for Gandhi’s INDIA alliance, which won 232 seats in the elections for the Lok Sabha, the lower house of parliament — below the halfway mark of 272 but significantly more than exit polls had predicted. Modi’s BJP won 240 seats, falling short of a majority on its own and leaving it dependent on allies to form a government for the first time since Modi came to power in 2014.

Gandhi’s omission was no one-off. It was part of a pattern, say analysts, observers and many Indian Muslims – one that has seen opposition parties demonstrate seeming reluctance to even mention Muslims.

“They know that a large part of India’s [predominantly Hindu] middle class is radicalised to the extent that taking the name of Muslims might harm the fortunes of political parties,” Mohammed Ali, an award-winning journalist based in New Delhi, said, speaking of Gandhi’s Indian National Congress party and other opposition groups.

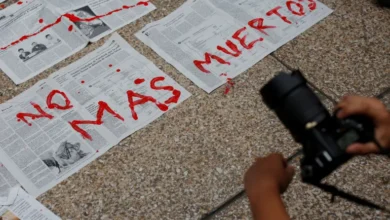

As India’s multiphase national elections drew to a close with the declaration of results, the curtains also came down on a campaign that turned increasingly vitriolic towards Muslims. Modi himself faced a warning from the Election Commission after a series of speeches that critics said represented hate speech. He referred to Muslims as “infiltrators” and “those who have more children”. And he referenced a series of Islamophobic tropes that have been widely debunked.

A Muslim youth who asked to remain anonymous said the elections were like a nightmare. “It was six weeks of nonstop anti-Muslim dog whistles. We do not feel part of this process,” he said.

Yet, through it all, many Indian Muslims say they also felt let down by the country’s so-called secular opposition parties, many of whom refused to even refer to their fears and concerns. That is reflected in a parliamentary landscape that, on its surface, appears contradictory.

Opposition avoids using word ‘Muslim’

The leaders of the opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA) did criticise Modi for bringing religion into his campaign. But analysts and many within the Muslim community point out that the opposition largely avoided raising Muslim concerns.

Dozens of Muslims have been lynched over accusations of cow smuggling as their food choices and public prayers have come under attack from vigilantes. Governments in several BJP-ruled states have enacted laws to prevent interfaith marriage – pandering to the conspiracy theory of “love jihad”, which suggests, without evidence, that Muslim men try to marry non-Muslim women to convert them to Islam.

And in 2020, India’s capital, New Delhi, witnessed riots in which at least 53 people were killed, most of them Muslim.

The Congress party and its alliance partner the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which governs Delhi, were silent on justice for the victims of those riots during the campaign – a sore point for people like Nisar Ahmad, a resident of Mustafabad in East Delhi.

Ahmad, who is one of the witnesses in court cases related to the Delhi riots, said he cannot forget how his neighbours were beaten, stripped and killed. “For me, everything has changed since the riots. I still feel unsafe in my own country,” he said.

“No one is talking about Muslims. The politicians fear if they use the word Muslim in their campaigns, it might hurt their vote bank,” Nisar said, referring to the opposition’s reluctance to discuss issues important to Muslims in campaign speeches. “I have voted and still hope somewhere that things might change.”

Others echoed his sentiments in Jamia Nagar, another Muslim neighbourhood in South Delhi.

“In previous elections, many politicians visited the area, and we would feel there is an election vibe,” Muhammad Shakir told Al Jazeera. This time, though, he said, “There has been no talk about our issues and local problems.

“It feels like everyone is ignoring Muslims deliberately,” he said.