Nuclear fusion: new record brings dream of clean energy closer

Nuclear fusion has produced more energy than ever before in an experiment, bringing the world a step closer to the dream of limitless, clean power.

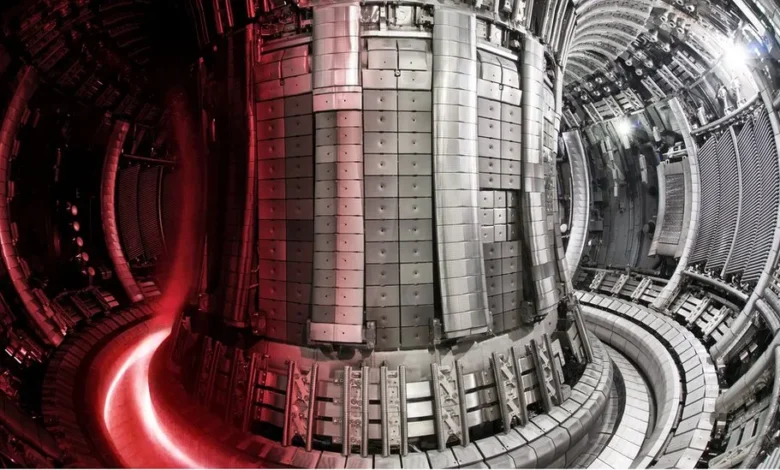

The new world record has been set at the UK-based JET laboratory.

Nuclear fusion is the process that powers stars. Scientists believe it could produce vast amounts of energy without heating up our atmosphere.

European scientists working at the site said “we have achieved things we’ve never done before”.

The result came from the lab’s final experiment after more than 40 years of fusion research.

Andrew Bowie, UK Minister for Nuclear, called it a “fitting swansong”.

Nuclear fusion is the process that powers the Sun. It works by heating and forcing tiny particles together to make a heavier one which releases useful energy.

If successfully scaled up to commercial levels it could produce endless amounts of clean energy without carbon emissions. And crucially unlike wind and solar energy would not be at the mercy of weather conditions.

But as Dr Aneeqa Khan, Research Fellow in Nuclear Fusion, University of Manchester explained, this is not straightforward.

“In order for the atoms to fuse together on Earth, we need temperatures ten times hotter than the Sun – around 100 million celsius, and we need a high enough density of the atoms and for a long enough time,” she explained.

The experiments produced 69 megajoules of energy over five seconds. That is only enough energy for four to five hot baths – so not a lot.

It is clear we are still a long way off from nuclear fusion power plants, but with every experiment it is bringing us one step closer.

Prof Stuart Mangles, Head of the Space, Plasma and Climate Research Community, Imperial College London, said: “The new results from JET’s final run are very exciting.

“This result really highlights the power of international collaboration, these results wouldn’t have been possible without the work of hundreds of scientists and engineers from across Europe.”

The Joint European Torus (JET) facility, was constructed in Culham in Oxford in the late 1970s and until the end of last year was the world’s most advanced experimental fusion reactor. All experiments ceased in December.

Although based in the UK it was funded predominantly by the EU nuclear research programme, Euratom, and operated by the UK Atomic Energy Agency. For four decades it hosted scientists from the UK, Europe, Switzerland and Ukraine.

The reactor was only meant to be operational for a decade or so but repeated successes saw its life extended. The result announced today is triple what was achieved in similar tests back in 1997.

Prof Ambrogio Fasoli, programme manager at EUROfusion, said: “Our successful demonstration… instils greater confidence in the development of fusion energy. Beyond setting a new record, we achieved things we’ve never done before and deepened our understanding of fusion physics.”

UK Minister for Nuclear and Networks, Andrew Bowie, said: “JET’s final fusion experiment is a fitting swansong after all the ground-breaking work that has gone into the project since 1983. We are closer to fusion energy than ever before thanks to the international team of scientists and engineers in Oxfordshire.”

But the future role of the UK in European fusion research has been unclear. Since Brexit the UK has been locked out of the Euratom programme and last year the government made the decision not to re-join.

Instead the government said it would commit £650m to national research programmes instead.

The Euratom successor to JET is a facility called ITER that will be based in France. Originally planned to be open in 2016 and cost around 5bn euros, its price has since roughly quadrupled and its start-up pushed back to 2025. Full-scale experiments are now not foreseen until at least 2035.

Although no reason was given for the UK government’s decision not to re-join Euratom the delays with ITER are believed to have played a part. At the time a spokesperson for the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero said: “Given delays to association and the direction of travel of these EU programmes, an alternative approach gives the UK the best opportunity to deliver our fusion strategy.”

At the announcement of the record on Thursday, Ian Chapman, from UKAEA, did say that discussions were still ongoing with European partners to see how the UK could be involved with ITER in the future.

The government is now hoping to build the world’s first fusion power plant in Nottinghamshire with operations beginning in the 2040s. The Spherical Tokamak for Energy Production (STEP) project will be delivered by a new nuclear body, the UK Industrial Fusion Solutions.