Toxic run-off from roads not monitored

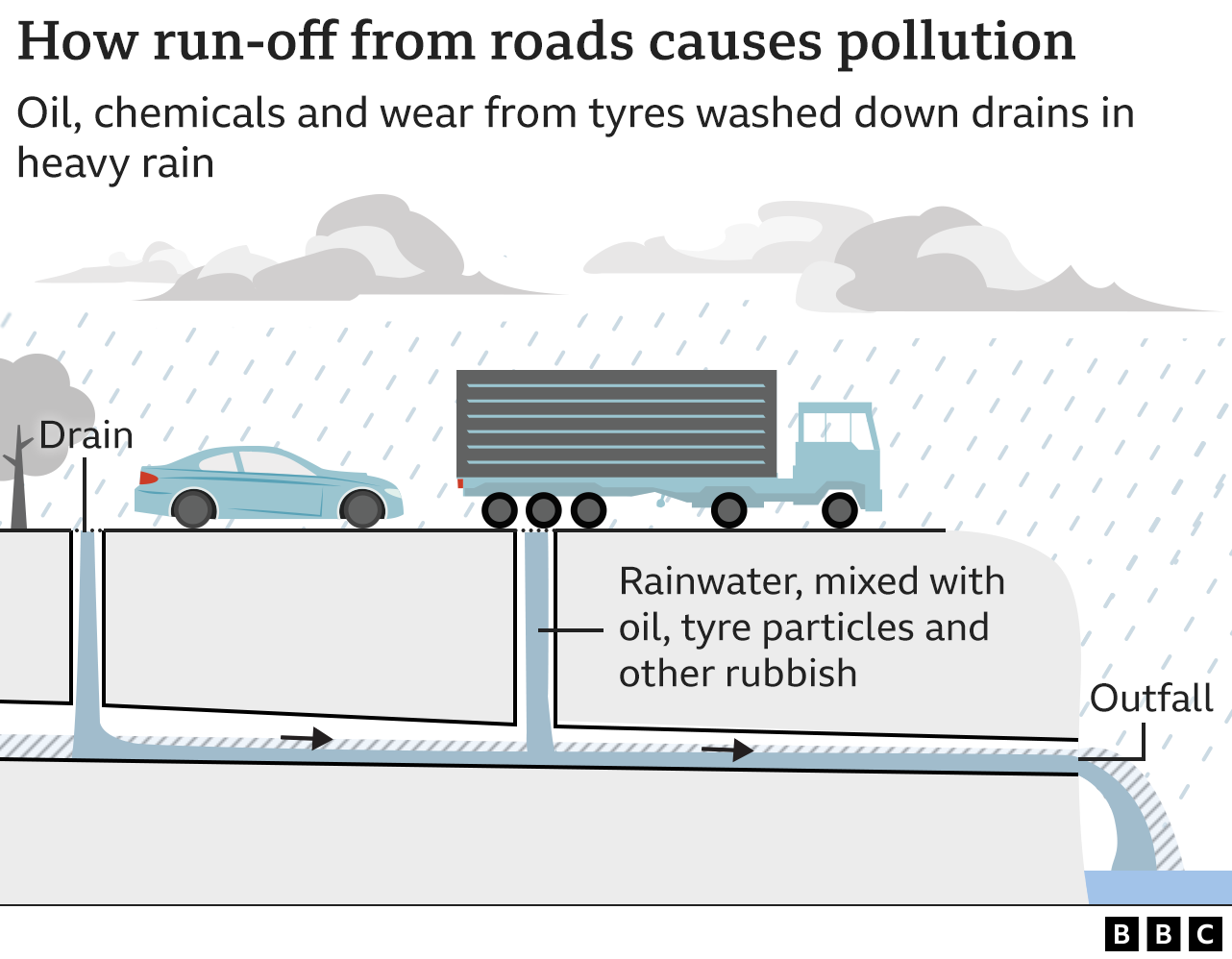

A toxic mix of oil, chemicals and bits of tyre from roads is polluting English waterways and no-one is regularly monitoring it.

Heavy rain forces run-off into streams and rivers. Campaigners say it causes “absolutely horrific” damage in places, including just downstream of where The Great British Bake Off is filmed.

England’s major road network has more than 18,000 outflows or drains.

National Highways runs the network and says it’s working to improve them.

Responsibility for monitoring water pollution in England rests with the Environment Agency.

In response to a BBC News freedom of information request, it said that the agency did not regularly monitor run-off, though it did test for pollutants from roads as part of its general water monitoring.

The EA said it recognised that run-off from highways and urban areas was a “serious issue” accounting for 18% of water quality failures in England, and the third most damaging source of water pollution after agriculture and sewage.

Campaigners have been doing their own testing and said that they had found micro-plastics, heavy metals, toxic chemicals like arsenic and carcinogenic compounds from car tyres.

Prof Alex Ford, an expert on the impact of water pollution on aquatic organisms at the University of Portsmouth, said that some of the contaminants are known to damage DNA, impact the nervous system and cause cancer.

“We don’t fully understand the impact these contaminants have as a cocktail but we know they can be toxic to aquatic life and potentially contribute to the poor ecological status of some rivers,” he said.

The Environment Agency can issue permits for activities that have the potential to cause pollution. They set out the limits to the pollution and can set rules the polluter must follow to keep environmental harm to a minimum.

Sewage outfalls have permits and MPs have in the past urged the EA to put permits on outfalls. But the EA has chosen not to saying it “would not result in reduced pollution”. It did say that it was looking at “possible benefits of using permits for some of the most polluting outfalls”.

“We are working to reduce all sources of pollution damaging the environment, whether they are from our roads, or water and farming industries,” an Environment Agency spokesperson told the BBC.

‘Bake Off’ stream polluted

At the River Lambourn in Berkshire the environmental impact of run-off can be seen very clearly.

A chalk stream, the Lambourn’s crystal clear water winds through Welford Park, home of The Great British Bake Off’s white tent, before passing underneath the M4 motorway.

At that point it turns brown and murky. Chalk streams are supposed to have clean gravel beds.

“Look at this black gunk,” Charlotte Hitchmough, the director of Action for the River Kennet (of which the Lambourn is a tributary) says as she scrapes a net along the bottom. In the past she has sent samples of the “gunk” away to be tested.

“There’s some really scary pollutants in there. Things like arsenic, lots of heavy metals, lots of things from oil, microplastics from tyres, we can be sure that the road is having a really negative effect on the ecology of this river.”

National Highways has a statutory responsibility to make sure that discharges from its network do not cause pollution. It said this outfall had been assessed as “low risk” and was not in line for any mitigation measures.

‘Absolutely horrific’

Just by the M6 services at Chorley we visit an outfall that National Highways cannot find a record of on their database.

“It literally keeps me awake at night,”says Jo Bradley, a former Environment Agency employee who has now dedicated herself to raising awareness of road run-off.

“This little stream should be beautiful,” Jo says as we look at what the map says is Syd Brook, at this point a murky pool of water topped with foam. “It’s absolutely horrific.”

When it rains, water from the M6 motorway drains directly into the stream. Jo shows me a plastic bottle full of brownish black water that she gathered during heavy rain the day before.

Her organisation Stormwater Shepherds has found tyre particles and dust from clutch and brake pads in the water.

“Because of the toxicity and the poisons in the sediment I would put this on a par with sewage (pollution) and to be frank, I’d probably put it above sewage,” she says.

“Because they’re not being monitored, no-one even knows the extent of the pollution and then nobody’s doing anything about it. Nobody wants to talk about this.”

National Highways is aware it has a problem and has been using a computer model to choose which outfalls to tackle. It has identified 1,236 locations that are “potentially high risk” and is expecting after verification that about 250 will actually be “high risk” and need some form of mitigation.

Under its current plans only about 30 of those high-risk sites will have mitigation in place by the end of 2025. A committee of MPs last year called that “unacceptably slow progress”.

“We do take this incredibly seriously – we think it’s important and we think there’s more for us to do,” Stephen Elderkin, National Highways director of Environmental Sustainability told BBC News.

“And so what we have set in place is a plan to identify those outfalls that present an elevated risk, to design mitigations that need to be put in place and then to deliver them before 2030.”

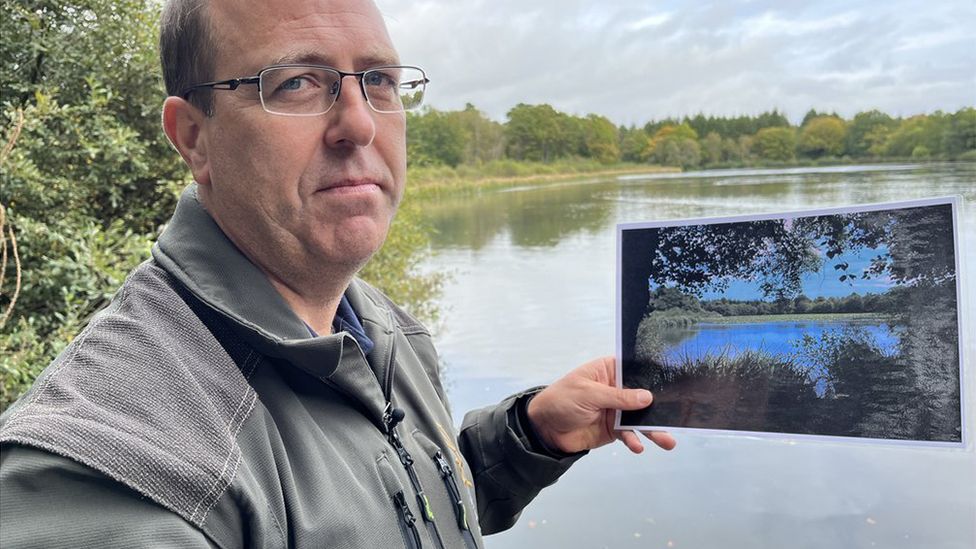

One of those mitigations is just off the A38 in Devon. At a cost of about £2.5m National Highways in 2019 built a reed bed that filters run-off from the busy road.

“This is a good news story,” says Rob Ballard, senior ranger at Stover Country Park. He’s holding a picture that shows how the lake used to look, with much of it covered with water lilies.

“It was almost like a Monet painting,” he says.

The water lilies aren’t fully back yet but Rob says they’ve seen the return of a whole raft of species which suggest the health of the lake is improving.

“We’ve got damselflies and dragonflies, little water boatmen, whirligig beetles, water scorpions and because of all of them, we get all the birds that feed off them,” he says.

The next step is to dredge the lake of all the heavily polluted silt that remains at the bottom.