European mission approved to detect cosmic ripples

What will be one of the most ambitious and most expensive space missions ever mounted by Europe has just been given the formal green light.

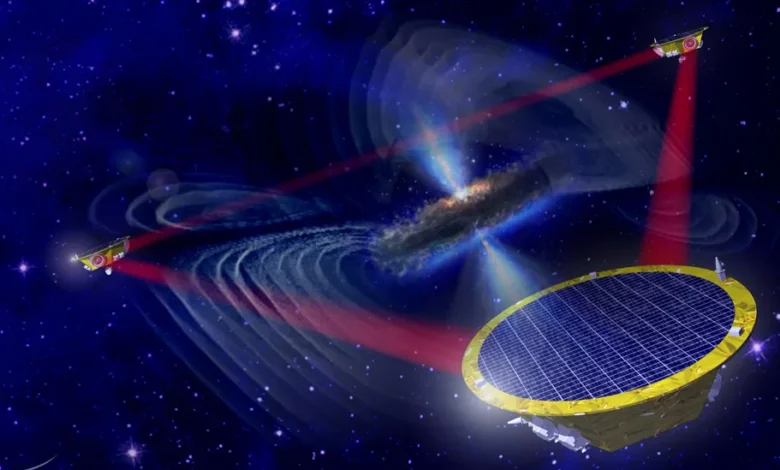

The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (Lisa) will try to detect ripples in the fabric of space-time generated when gargantuan black holes collide.

These gravitational waves will be sensed by three spacecraft firing lasers at each other over a distance of 2.5 million km (1.5 million miles).

The cost will run into the billions.

Scientists believe that studying gravitational waves will help answer important questions about the workings and history of the Universe.

Officials at the European Space Agency (Esa) forecast a budget of €1.75bn (£1.5bn; $1.9bn), with additional contributions coming from member states including Germany, France, Italy, the UK, the Netherlands and Switzerland. The US space agency (Nasa) will be a major partner, too.

While this sum is considerable, it does represent a life-time cost – and the complexity of the mission means it will not launch before 2035 at the earliest.

Esa’s director of science, Prof Carole Mundell, likened the cost to each European citizen to that of a cup of coffee, and she hoped they would agree with her that this represented great value for money.

“We’re trying to solve some of the big mysteries of physics,” she said.

“How do we go beyond Einstein’s theory of general relativity (his theory of gravity)? How do we probe the nature of space-time? How do we understand the most violent collisions in the Universe, between supermassive black holes? So, you bring together what is almost science fiction and the science engineering, and we make it a science reality.”

Gravitational waves are a prediction of Einstein’s equations.

They are the ripples of energy that spread across the cosmos at the speed of light when masses accelerate.

The waves were first detected in Earth laboratories in 2015. They were produced by the coming together of black holes that were a few times the mass of our Sun.

Going into space with detectors will allow researchers to sense much longer wavelength phenomena.

“It’s all about size. With Lisa we’re talking about sensing the coming together of black holes that are millions of times the mass of our Sun,” said Prof Harry Ward from Glasgow University, UK.

Scientists are particularly keen to study these supermassive objects because their creation and evolution seems to be tied inextricably to that of the galaxies that host them, and probing their properties would therefore reveal details about how the great structures we see on the sky took shape through cosmic history.

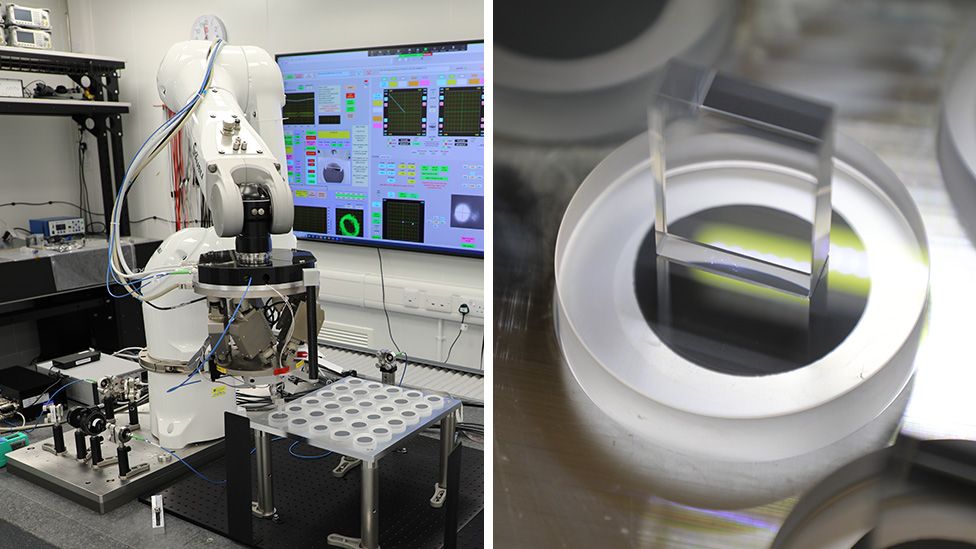

On Earth, gravitational waves are detected from the perturbations they induce in the path of laser light as it is fired down 4km-long, L-shaped tunnels.

Lisa will use the same principle but fire its beams over a much greater distance, and between three identical spacecraft arranged as an equilateral triangle.

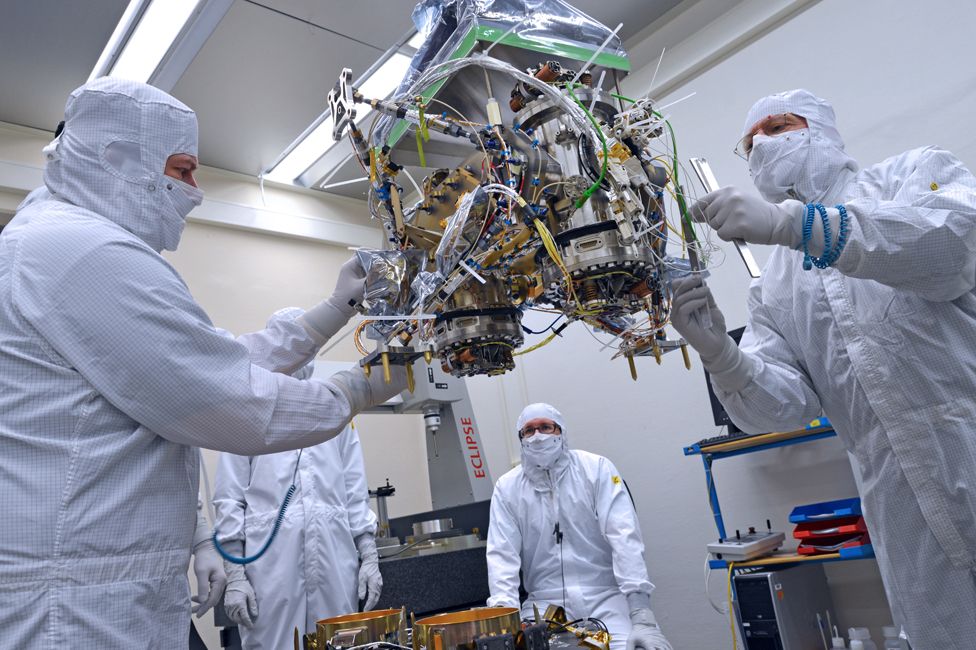

Astonishing measurement precision is needed because although the waves come from colossal sources, their signal is tiny – just fractions of the width of an atom.

Scientists talk about picometres, which are a trillionths of a metre.

“If you scale it up, it’s the equivalent to measuring the change in distance to Alpha Centauri to about the thickness of a piece of paper,” said Dr Ewan Fitzsimons at the UK Astronomy Technology Centre (UK ATC). Alpha Centauri encompasses the closest star system to Earth and is more than four light-years away.

Lisa has already been in development for decades, and has gone through various ups and downs, not least with the participation of the Americans. They’ve been in and out, but are now fully back on board, and will bring important technologies, including the lasers.

Esa’s Science Programme Committee (SPC) selected Lisa as a candidate mission in 2017. Since then the agency’s technical staff, with support from European industry and academia, have been studying whether the mission is actually feasible. A positive assessment has now allowed Esa delegations to formally “adopt” the project.

The UK Space Agency has given its support although this has the reservation that a business case still needs to be made to His Majesty’s Treasury. This will be submitted shortly and a decision is expected before the end of the year, after which Esa will look to place the major industrial contracts across Europe.

Britain is set to provide what are called the optical benches in the spacecraft. These are the mirror systems that corral the laser light beams so their behaviour can be precisely monitored. One of the main data distribution centres will also be hosted in the UK.