Amazon’s record drought driven by climate change

One of our planet’s most vital defences against global warming is itself being ravaged by climate change.

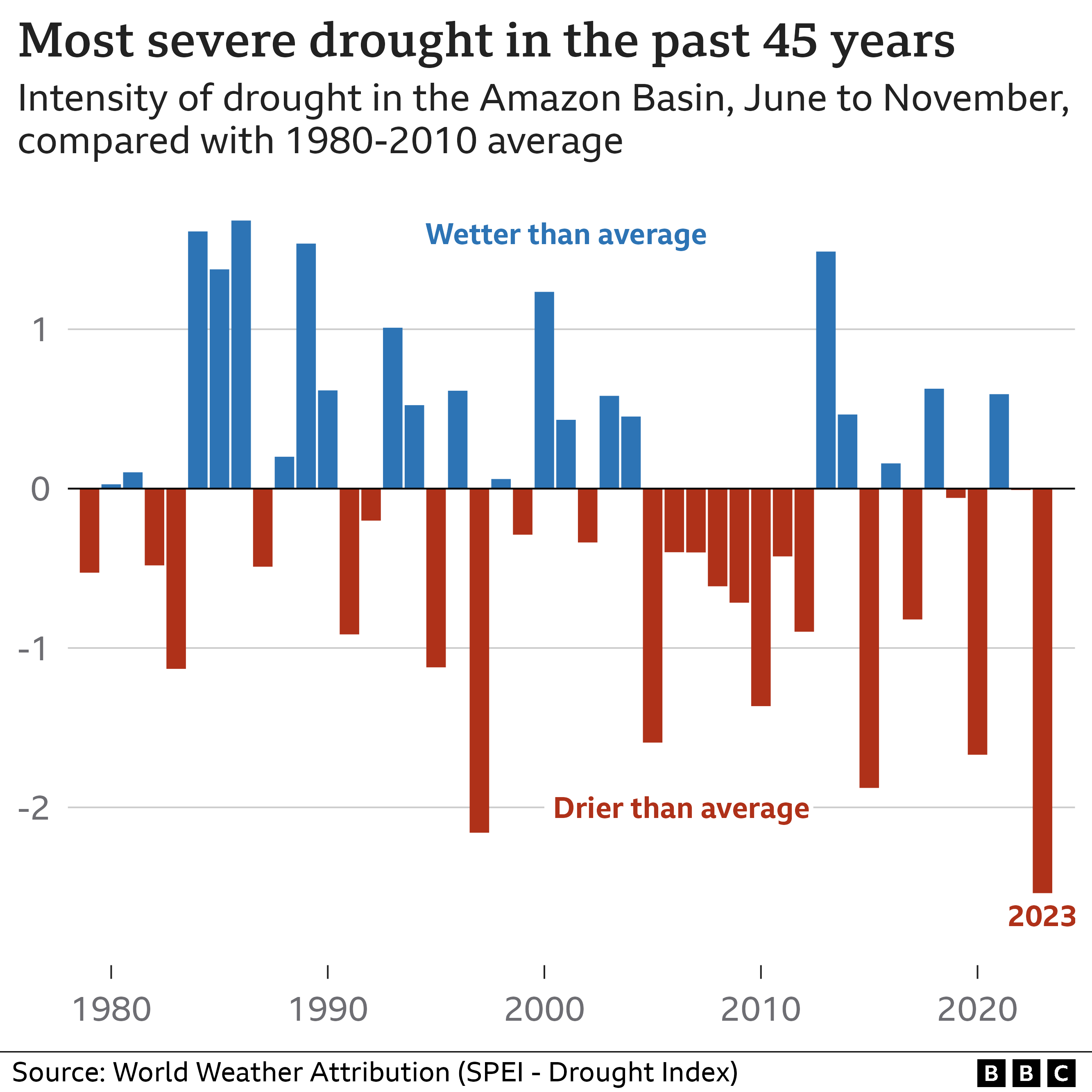

It was the main driver of the Amazon rainforest’s worst drought in at least half a century, according to a new study.

Often described as the “lungs of the planet”, the Amazon plays a key role in removing warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

But rapid deforestation has left it more vulnerable to weather extremes.

While droughts in the Amazon are not uncommon, last year’s event was “exceptional”, the researchers say.

In October, the Rio Negro – one of the world’s largest rivers – reached its lowest recorded level near Manaus in Brazil, surpassing marks going back over 100 years.

As well as being a buffer against climate change, the Amazon is a rich source of biodiversity, containing around 10% of the world’s species – with many more yet to be discovered.

The drought has disrupted ecosystems and has directly impacted millions of people who rely on rivers for transport, food and income, with the most vulnerable hit hardest.

One trigger for these dry conditions is El Niño – a natural weather system where sea surface temperatures increase in the East Pacific Ocean. This affects global rainfall patterns, particularly in South America.

But human-caused climate change was the main driver of the extreme drought, according to the World Weather Attribution group, reducing the amount of water in the soil in two main ways.

Firstly, the Amazon is typically receiving less rainfall than it used to between June and November – the drier part of the year – as the climate warms.

Secondly, hotter temperatures mean there’s more evaporation from the plants and soils, so they lose more water.

The researchers used weather data and computer simulations to compare drought conditions in two scenarios: one with human-caused warming, and one without.

In a world where humans hadn’t heated up the planet by around 1.2C, such an intense ‘agricultural drought’ – where a lack of rainfall and high evaporation dry out the soils – may only have happened around once every 1,500 years, the study suggests.

Climate change has made a drought of this severity around 30 times more likely, according to the researchers, and one is now expected to happen every 50 years under current conditions.

“This really is something quite exceptional,” says Dr Ben Clarke, a researcher with the World Weather Attribution group.

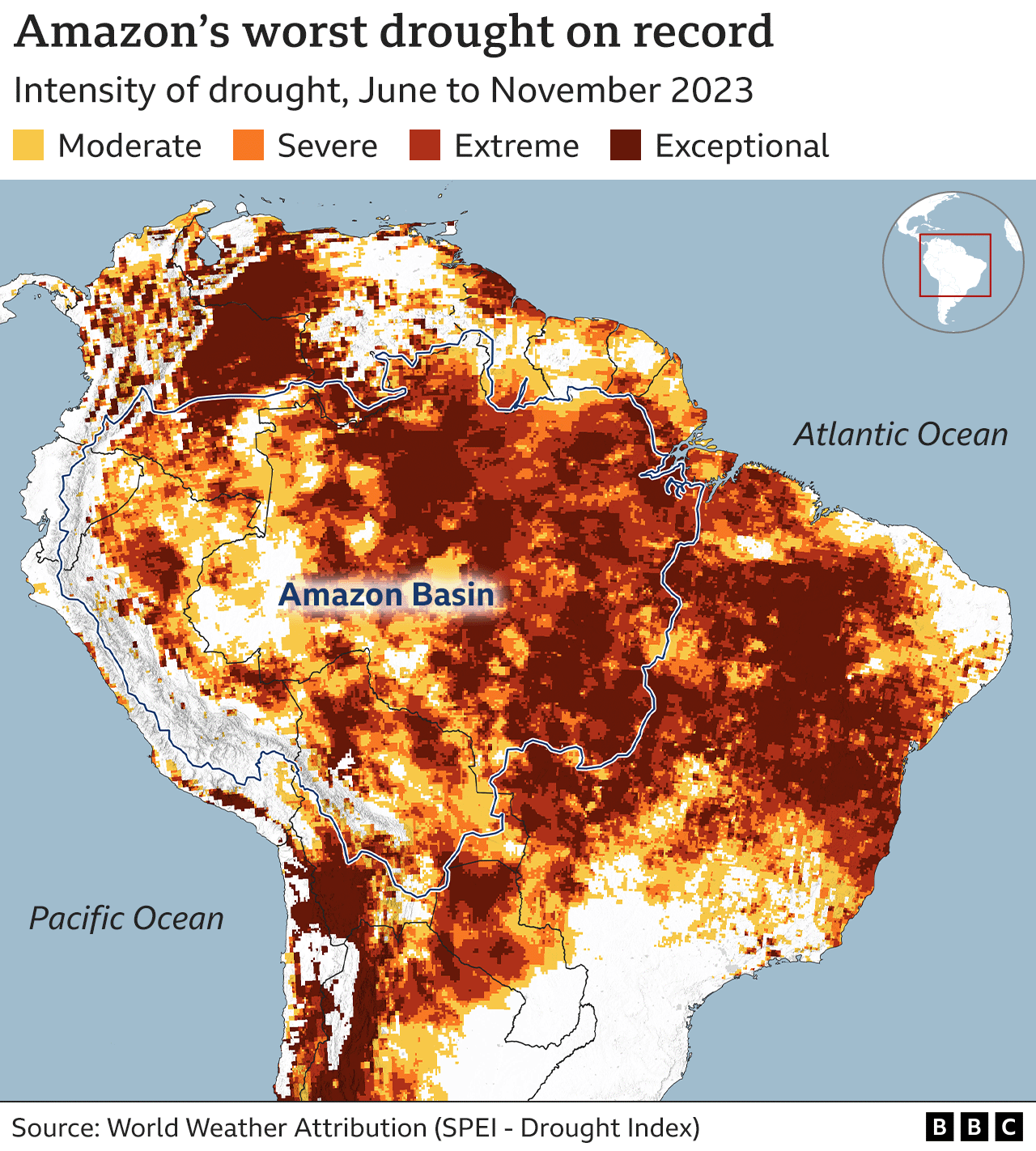

As the map below shows, drought hit almost all of the Amazon basin. This scale – and intensity – makes it different to previous droughts, Dr Clarke said.

And if warming continues, such extreme droughts could become even more common.

“If we continue burning oil, gas and coal, very soon, we’ll reach 2C of warming and we’ll see similar Amazon droughts about once every 13 years,” says Dr Friederike Otto, a senior lecturer in climate science at Imperial College London.

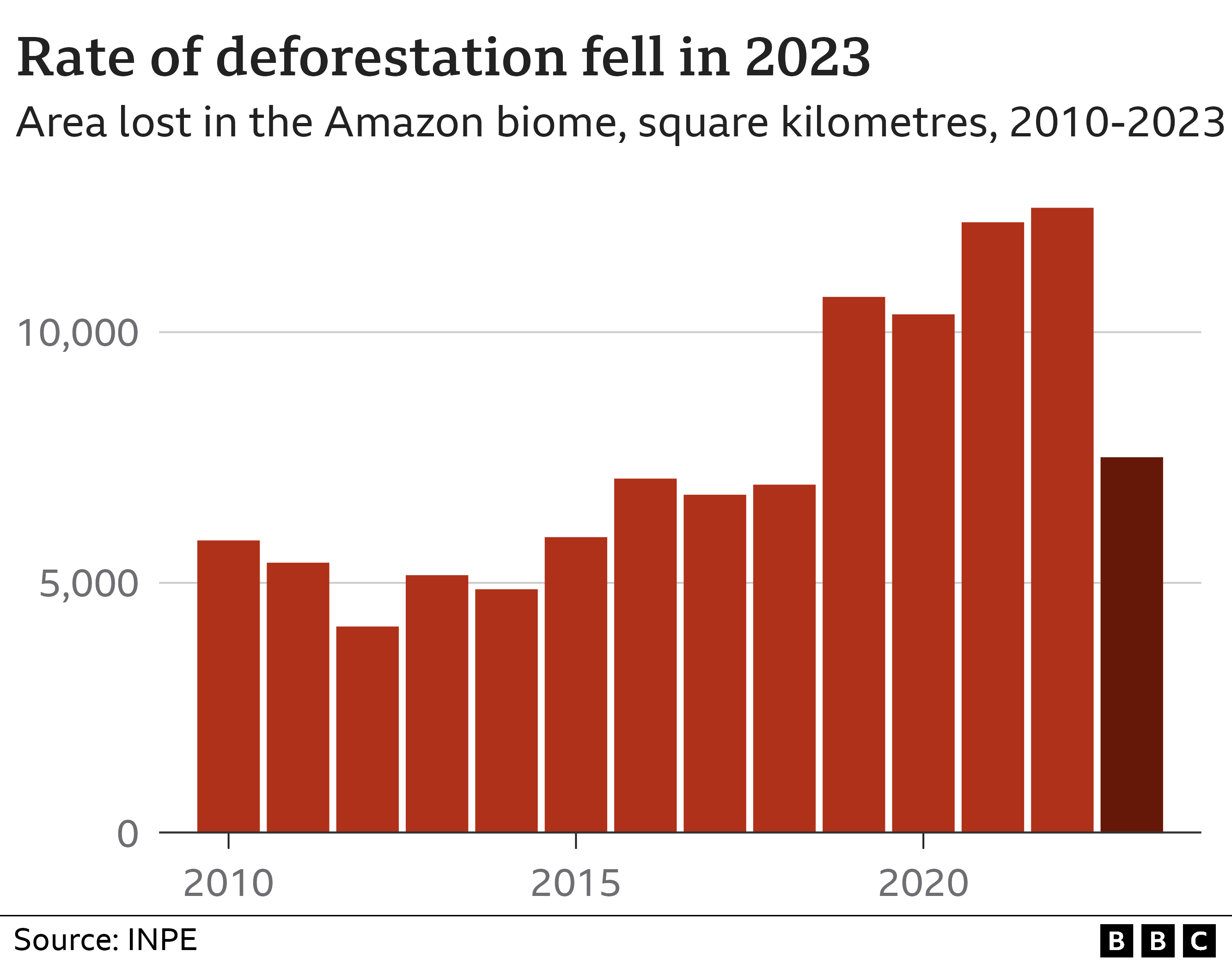

More frequent and intense droughts test the Amazon’s resilience. That has already been stretched by deforestation – around one-fifth of the rainforest has been lost over the last 50 years.

Trees help the area retain and release moisture, fuelling their own clouds, and they also help to cool temperatures.

While the effect of deforestation was not directly tested in this latest study, previous research has shown it increases the vulnerability of the rainforest to drought.

Lungs of the planet

The world’s largest rainforest is seen as crucial in the battle to limit global warming.

“The Amazon could make or break our fight against climate change,” says Regina Rodrigues, a professor of physical oceanography and climate at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Brazil.

In a healthy state, it takes up more carbon dioxide (CO2) than it releases.

This limits CO2 increases in the atmosphere from human activities, keeping a lid on temperatures.

But there is evidence that this may be changing, as trees die back due to drought, wildfires and deliberate clearance to make room for agriculture.

There is concern that if climate change and deforestation continue at their current pace, the Amazon could soon reach a “tipping point”.

If crossed, this could lead to the rapid and irreversible dieback of the whole rainforest – potentially leading to the region becoming a significant source of CO2 emissions.

It’s not known exactly where such a threshold might sit.

“I don’t think that [tipping point] is what we are seeing [yet], at least in all but the driest part of the Amazon forest,” says Yadvinder Malhi, a professor of ecosystem science at the University of Oxford, who was not involved in the latest study.

Despite the latest record drought, there has been some encouraging progress.

The rate of deforestation fell in 2023 compared with the year before, according to the Brazilian space agency, with President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva pledging to halt it completely by 2030.

This – alongside urgent action to slash the greenhouse gas emissions that are fuelling global warming – can still help to protect what’s left of the Amazon, researchers say.

“The loss of the Amazon forest is far from inevitable in the short-term,” as long as fire and deforestation can be controlled, Prof Malhi said.

“But we do need to get to grips with stabilising global climate, as the risk increases with every fraction of a degree the planet warms.”