Fears simmer in Essequibo region as Venezuela eyes the disputed territory

The threat had always been there, ever since Lloyd Perreira was a young child: that one day his ancestral home could be absorbed into the neighbouring country of Venezuela.

A member of the Lokono Indigenous people, Perreira considers his home Essequibo, a vast territory on the western flank of Guyana. He grew up in Wakapoa, a village composed of 16 islands on the Pomeroon River, nestled in the heart of the region.

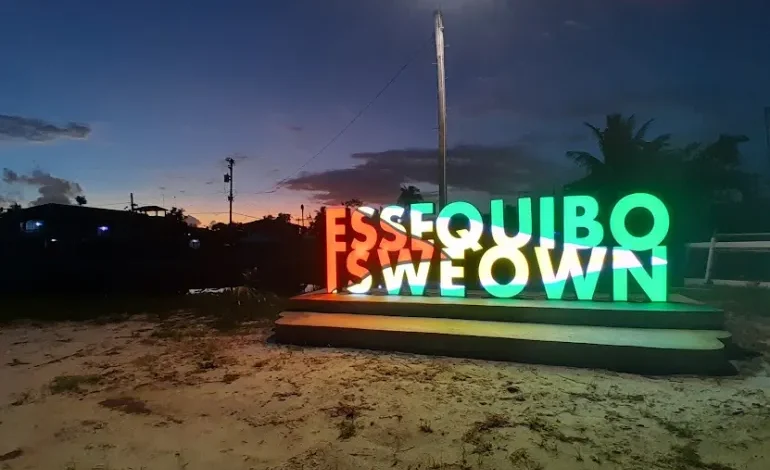

“Even as a small boy, I remember hearing Venezuela saying Essequibo is theirs,” Perreira said. “But I also know I live in Essequibo, and as an Indigenous person, Essequibo is ours.”

Perreira is now the toshoa, or chief, of Wakapoa. But his childhood fears returned when Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro recently held a referendum to claim Essequibo as his country’s own.

“We were very scared when we saw the referendum,” Perreira said, as he picked a harvest of rare liberica coffee beans.

Though tensions have subsided since the December 3 referendum, the ongoing question of whether Essequibo could be annexed to Venezuela has sparked anxiety among those who call the territory home.

Nearly two-thirds of what is considered Guyana lies in Essequibo, a 159,500-square-kilometre (62,000sq mile) area lush with jungles and farms.

Along the Pomeroon River, coconuts are cultivated to make oil. Coffee shrubs blossom from riverbanks. And Indigenous groups like the Lokono harvest cassava for bread and cassareep, a syrup used to preserve food.

But the discovery of large oil deposits off its shores in 2015 reignited a decades-long territorial dispute over Essequibo. Experts estimate that more than 11 billion barrels of oil and natural gas could sit within its territory.

In recent months, Maduro has framed Venezuela’s claims on the land as a “historic battle against one of the most brutal dispossessions known in the country”.

The referendum his administration put before voters consisted of five questions, asking them to reject 19th-century arbitration that awarded Essequibo to Guyana and instead support the creation of a Venezuelan state.

That the referendum passed with 98 percent support fueled fears in Guyana that a Venezuelan takeover may be imminent.

“Guyana has never been in any war,” taxi driver Eon Smith told Al Jazeera in the town of Charity, southeast of Wakapoa. “We are not prepared for war. What will we do?”

Those concerns have also translated into lower attendance at Wakapoa’s local boarding school. Students who usually travelled for miles to attend instead stayed home in the lead-up to the referendum, their dormitory beds sitting empty.

“We have one boy in the dormitory,” teacher Veneitia Smith said, pointing to a flat concrete dwelling. “Everyone else stayed away since we heard about the Venezuela referendum.”

But since the referendum, Maduro has proceeded to declare Essequibo “a province” of Venezuela. He also directed Venezuela’s state-owned companies to “immediately” begin exploration for oil, gas and minerals in the region.

Some Guyanese residents, however, have organised activities to protest the referendum. Those demonstrations ranged from prayer meetings to school performances of patriotic songs and chants.

Indigenous leaders like Jean La Rose, the executive director of the Amerindian Peoples Association (APA), also called on residents to stay in their villages — and resist any urge to leave preemptively.

La Rose herself returned to her home in Santa Rosa, a village in the Moruca subregion of northwest Essequibo. In a message posted on social media, she urged Indigenous peoples “to remain in their homes and guard them” in case of annexation.

“I want to encourage other people: Stay in your homes, that is what you own. Stay on your lands, that is what you own,” she said. “That is the patrimony of your forefathers, your ancestors. Stay, guard it.”