Climate change: How is my country doing on tackling it?

With world leaders at COP28 in Dubai, there is a renewed sense of urgency to limit emissions to curb the harshest impacts of climate change.

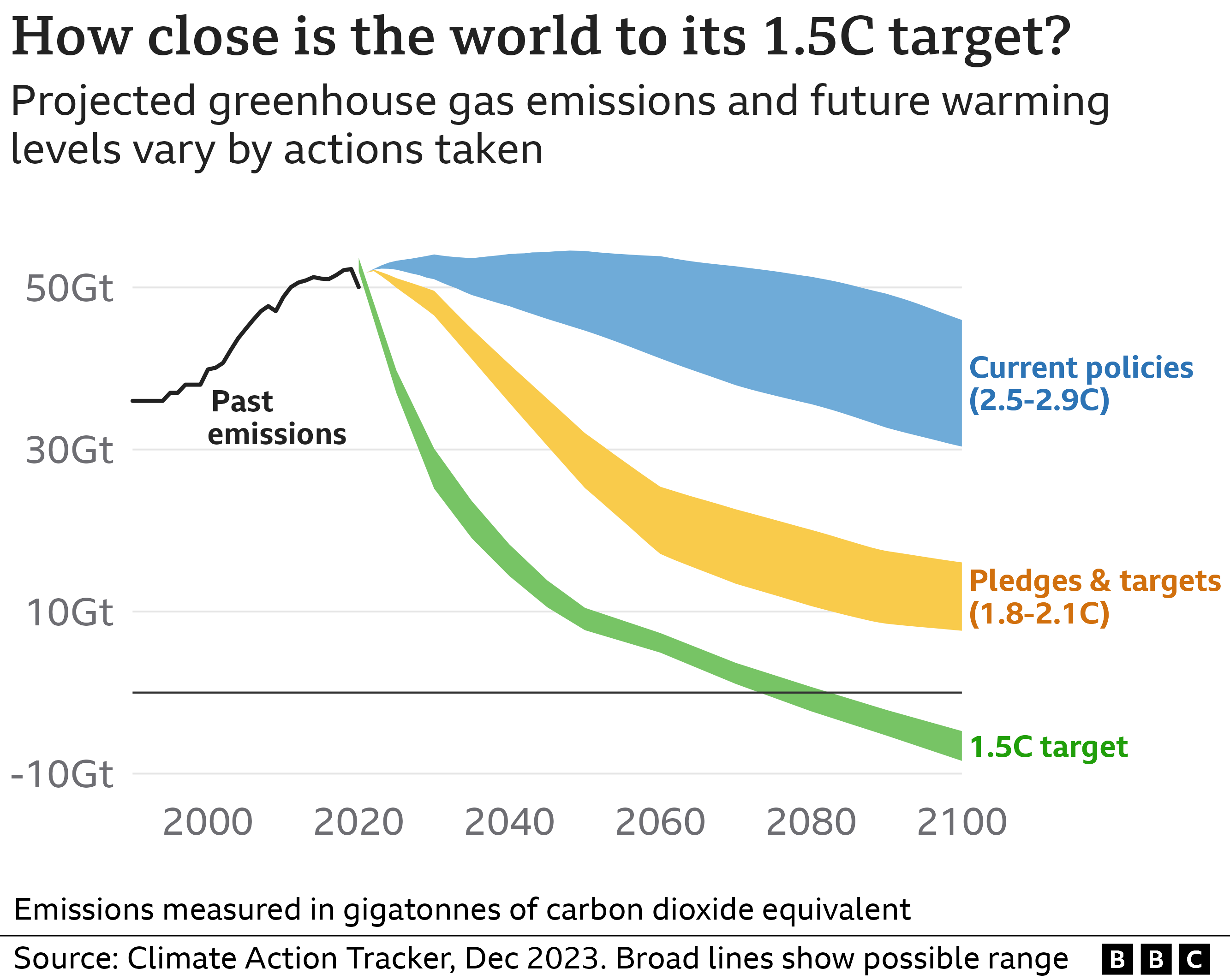

Many of these governments have pledged to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions in order to keep global warming levels below a 1.5C rise on pre-industrial levels.

But after months of record-shattering heat, 2023 is set to be the warmest year on record.

And scientists now anticipate average global temperatures to pass the 1.5C threshold within the next five years.

Use the interactive chart below to see which countries are on track with their commitments to meet the Paris climate goal of keeping global temperature rises below 1.5 degrees.

Not all countries can independently afford the same kinds of emissions-reducing actions.

Some less affluent countries set two different goals – one they aim to meet completely on their own, and a more ambitious one they aim to meet if they can get support from wealthy donors. We’ve only shown the independent targets here.

But the emissions debate is more nuanced than simple reductions.

Historical responsibility for climate change is not shared equally across all nations. So, a group of independent researchers at Climate Action Tracker, have devised a method to calculate what they call the “fair share” targets, which consider a country’s historical contributions to total global emissions as well as their current levels.

Countries that have contributed only a marginal amount to the overall total have a lesser “fair share” of responsibility than those that have been heavy emitters for many years.

By looking more closely at some individual countries, we can get a better sense of whether they are on or off track.

China

China is the world’s largest annual emitter of greenhouse gases.

And while it is less responsible for past contributions to global warming, China’s rapid economic growth in recent years has begun to tip that balance.

Some of this growth has gone hand in hand with the world’s fastest transition to renewable energies. China leads the world in its adoption of solar, wind and electric transportation.

But it has continued to rely heavily on coal, with no promised end.

Additionally, China – the world’s leading methane emitter – has not yet joined the more than 150 countries who have signed up for the Global Methane Pledge, which aims to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030.

US

After China, the United States ranks second for annual emissions.

Recent policy changes have taken steps towards meeting its targets. The Inflation Reduction Act was the country’s largest single investment in climate action.

And a joint statement with China ahead of COP28 promised the two countries would step up their cooperation on issues such as reducing methane and tripling renewable energy uptake. The statement fell short of setting new ambitious targets, though.

Bernice Lee, a distinguished Fellow at Chatham House and an expert on China, told the BBC at the time of the statement: “My suspicion is that it has proven to be too difficult to find the form of language that works for both. But nonetheless, I think it’s good that they have a statement that’s focused on the things they agree on, which is, obviously, the renewables and methane.”

But the US is still a long way from reaching its stated emissions goals, and it has continued to approve new oil drilling projects in the Gulf of Mexico.

Brazil

One year into his presidency, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has made some progress on reversing the destruction of the Amazon that took place under his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro.

In November 2023, Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research announced that deforestation in the Amazon hit a six-year low and the government is calling for the creation of a forest fund at COP28 to incentivise other nations to reduce deforestation.

Brazil has reduced its emissions pledge, but it continues oil exploration and plans to align itself more closely with Opec in future, undermining the ambitions announced.

Brazil has restated its emissions targets, but it continues oil exploration and plans to align itself more closely with Opec in future.

UK

Much of the UK’s success in lowering its emissions has come from the decarbonisation of the energy sector – by switching away from coal toward natural gas and, more recently, renewable sources.

Ambitious net zero targets have also been set by previous administrations.

But in 2023, the UK’s independent Climate Change Committee found only 20% of the emissions reductions needed to meet the UK’s Sixth Carbon Budget in 2035 were covered by viable policies.

Dr Mark Maslin, professor of earth systems at UCL, said: “UK progress toward net zero has been poor in 2023.

“This is because the government has weakened many of its green policies and granted new oil and gas licences, which are incompatible with a net zero future,” he added.

The government said the licences would slow the decline in domestic production of oil and gas and secure domestic energy supply.

Some recent global developments have been positive.

On the first day of COP28 the parties agreed to implement a specific “loss and damage fund”, seen as a major win for developing countries in particular.

This money will help poorer countries cope with the destruction caused by storms and droughts, which are expected to worsen with climate change.

For the first time, countries have agreed to include the greenhouse gas emissions from food and agriculture in their national plans to tackle climate change.

The world has also seen “impressive” uptake of clean energy sources, with record annual expansions in solar and wind capacity, according to the International Energy Agency.

And in the first week of COP28, around 100 countries have pledged to triple renewable energy use by the end of the decade.

However, the increase in clean energy has not seen a similar fall in fossil fuel use. In some places it is even expanding.

No matter the target, there is plenty of progress still needed.