Malta welcomes foreign workers to fill labour shortage, but repels refugees

Amit* cruised through the lanes of Marsaxlokk, a colourful Maltese fishing hamlet, on his way to pick up two passengers in his taxi.

“I love my job in this country,” he said. “Malta was my entry to Europe.”

Amit arrived this year from Bangladesh, having paid $3,200 to an immigration agency.

“I’m now earning around 1,000 euros [$1,085] per month, some of which I send home. It has been an expensive process, but I’m happy.”

A few streets away, Nita*, who is from northeastern India, waited for a bus to take her towards Malta’s capital, Valletta.

In recent years, the Maltese archipelago has become something of a hub, attracting thousands of migrants who fill labour shortages, especially in the hospitality, healthcare and service industries.

Former Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, who in a June 2014 speech said he aimed to turn Malta into the “next Dubai”, is credited with the migration flows in recent years.

In that speech, he also indicated that he aimed to mirror Dubai’s system of recruiting migrant workers from South and Southeast Asian countries through agencies.

“Being at the crossroads in the Mediterranean and the centre of the busiest shipping route in the world, our geography has always made us attractive to migrants who want to work in our country,” Muscat told Al Jazeera.

“But in recent years, we’ve faced labour shortages in some sectors like the service and healthcare industry and also have an ageing population. So introducing a system of bringing migrants in such a structured manner to the country was integral.”

Located in the Central Mediterranean, Malta is also an entry point to Europe for thousands of people from Africa, the Middle East and Asia fleeing conflict and poverty.

While Malta has accepted asylum seekers, rights groups have also accused the country of “illegal tactics” to turn refugees away, such as pushbacks at sea.

Daniel Mainwaring, an independent foreign policy and migration researcher from Malta, said Valletta has created “legal pathways” for foreigners who want to work in Malta but, when the government sees thousands of people arriving by sea seeking refuge, “then it is all about reducing overall migrant arrivals.”

“Contracted migrants are often seen as the good ones, and those that enter the country by sea are considered illegal. What is ironic is that they’re [sometimes] people coming from the same country,” Mainwaring said.

“For example, there are Bangladeshis who get visas with the help of agencies and enter Malta, and Bangladeshis whose visas get rejected for whatever reason, so they pick the sea route to enter Malta, seeking refuge.

“People from the same country of origin are coming in through two very different migratory pathways and are equally vulnerable but are being treated differently.”

Foreign workers for ‘these kind of jobs’

Non-European Union countries with a significant number of nationals working as contracted migrants in Malta include India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and the Philippines.

Private recruitment agencies sell the idea of working in Malta by offering attractive salaries. They also charge commission for helping people with Maltese residency documents.

“Our economy, like any other growing one, has witnessed upward social mobility, and this brought about a growing problem of lack of people who would want to or would be willing to go into certain jobs in the service industry, such as hospitality and healthcare,” Muscat said.

“Economic growth brought about migration with people from non-EU nations keen to do these kind of jobs and send money back to their home countries.”

But immigration agencies have been found by rights groups and investigative journalists to be engaging in exploitative practices, such as recruiting people to jobs that pay below the minimum wage with poor conditions. According to local media reports, some agencies have even been found to offer jobs that do not actually exist once migrants enter Malta.

“I have heard of stories of some people not getting paid properly or not getting a job after arriving. They have then been forced to leave,” Nita said. “While I am happy working here, I eventually want to get work elsewhere in Europe. Our living conditions here are still very poor. But I can’t complain since I have to support my family back in India.”

Neil Falzon, director of the Aditus foundation, a Maltese human rights organisation, told Al Jazeera that foreign workers who use recruitment agencies to get to Malta “do not enjoy much protection from the government”.

“The level of rights that they have is extremely low,” he said, “so we are really talking about modern slavery here.”

Muscat said dubious agencies involved in abusing workers’ rights should be punished and noted that the government has begun to take action. Prime Minister Robert Abela’s government has drafted new rules for recruitment agencies which are expected to come into force next year.

“It’s great that the government has acknowledged that there is a problem, but after big announcements, implementation of rules is slow,” Falzon said. “In many cases, the battle is less against the government and more against the private agencies who are employing and exploiting migrants. So we’re trying to push the government to have more stringent legislation to ensure better rights for contracted migrants,”

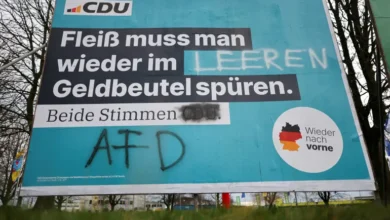

At the same time, some locals and far-right politicians have begun calling on the government to crack down on foreign labour.“[Some] local Maltese people want migrants to build and clean our roads but also blame them if there is crime. So then you’ll see the government clamping down on the African or Asian migrant community by arresting a few or revoking their residency status, all in an effort to show a couple of angry locals and far-right politicians that they’re managing migration,” Mainwaring said.

Muscat said, however: “We need non-Maltese workers for the simple reason that some of our sectors and our economy and crucial social sectors such as healthcare would collapse if it wasn’t for these people. So they need to be protected and the government is ensuring that.”

‘Legal migration won’t necessarily solve irregular migration’

Besides Malta, other EU nations like Hungary have also been bringing in migrants through recruitment agencies in recent years.

In July, Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni said she plans to bring in 450,000 non-EU migrant workers in the next two years as she simultaneously announced plans to stop refugee arrivals by sea.

Bram Frouws, head of the Mixed Migration Centre, said countries that quietly welcome foreign workers while adopting far more hostile policies on undocumented people do so “for political gain or to use migrants as a scapegoat”.

“While organising legal migration is exactly what is needed, the way irregular migration is being handled with the push and pullbacks, the abuses and deaths and the undermining of search and rescue at sea is a bigger issue,” he said.

“To a large extent, these European countries are also looking at other countries of origin for labour migrants than the nationalities of those arriving at sea. So the kind of legal migration they’re organising won’t necessarily solve the irregular migration by sea,” he added.