Lightning fires threaten planet-cooling forests

Climate change could bring more lightning to forests in northern reaches of the globe, increasing the risk of wildfires, a new study shows.

Researchers found that lightning is the main cause of fires similar to those seen in parts of Canada this summer.

These forests limit climate change by trapping planet-heating carbon.

More lightning could spark a vicious cycle, as trees and soil set ablaze release warming CO2 – creating more storms and potentially more lightning.

While the overall number of fires has decreased around the world over the last two decades, they have increased markedly in heavily forested areas outside the tropics.

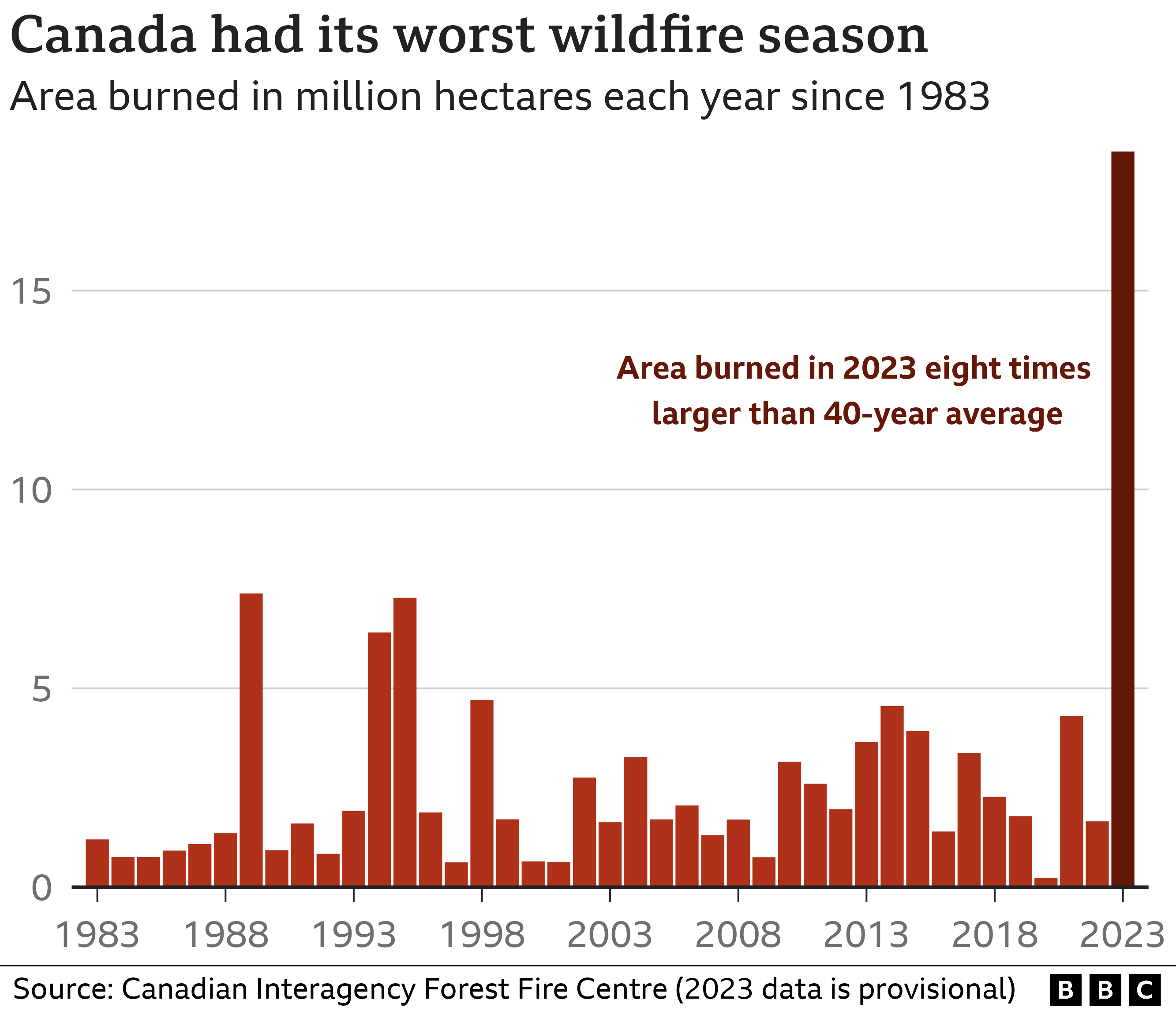

This year Canada experienced a fire season like no other – over 6,500 fires blazed, burning around 18 million hectares (45 million acres) of forest and land.

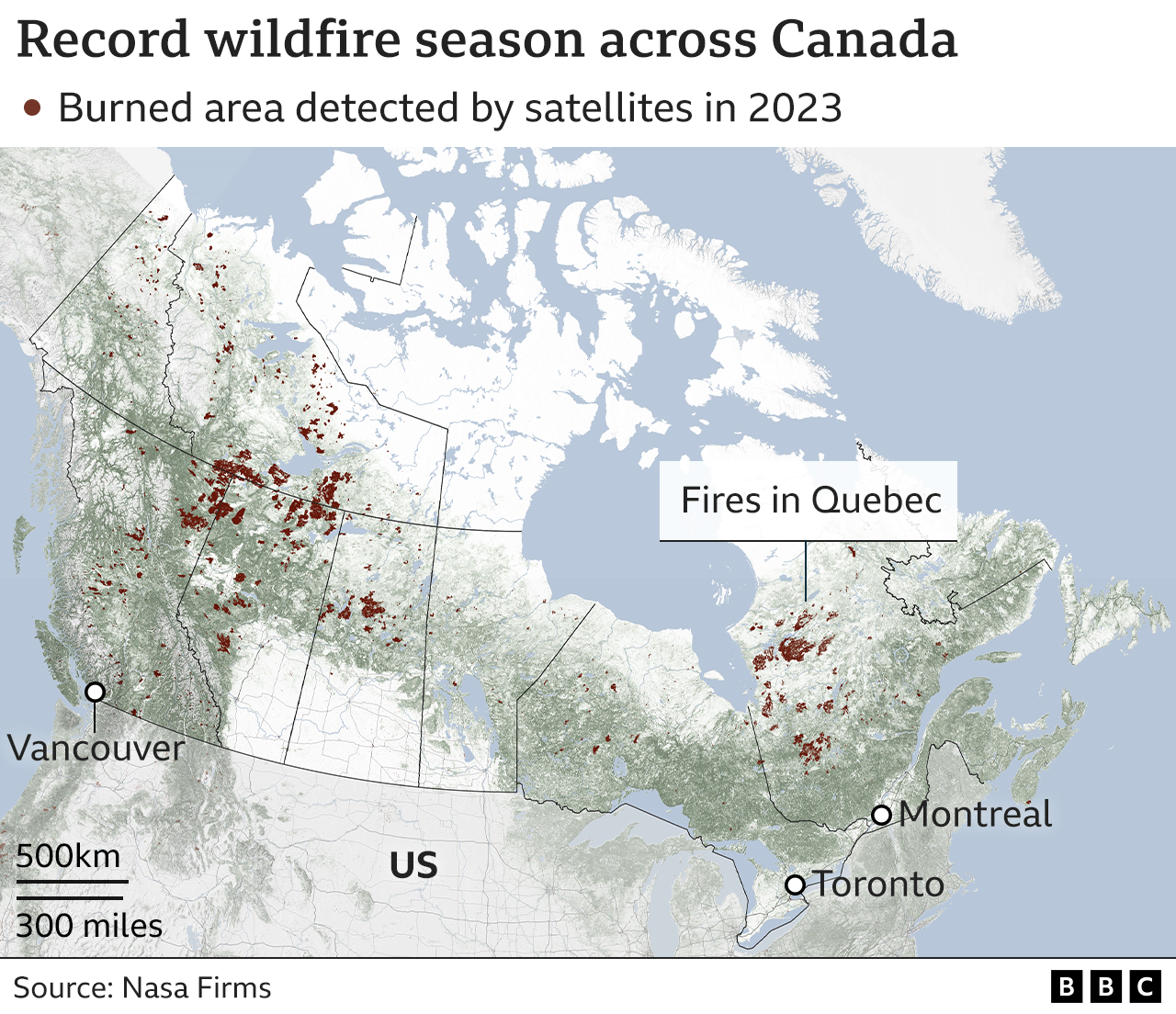

Smoke from those fires drifted into major cities in Canada and the US, even crossing the Atlantic to Spain and Portugal.

Unlike other years which saw fires confined to the western part of the country, 2023 was marked by conflagrations across the entire territory including in eastern regions like Quebec.

The majority of these fires in northern parts were started by lightning strikes according to experts.

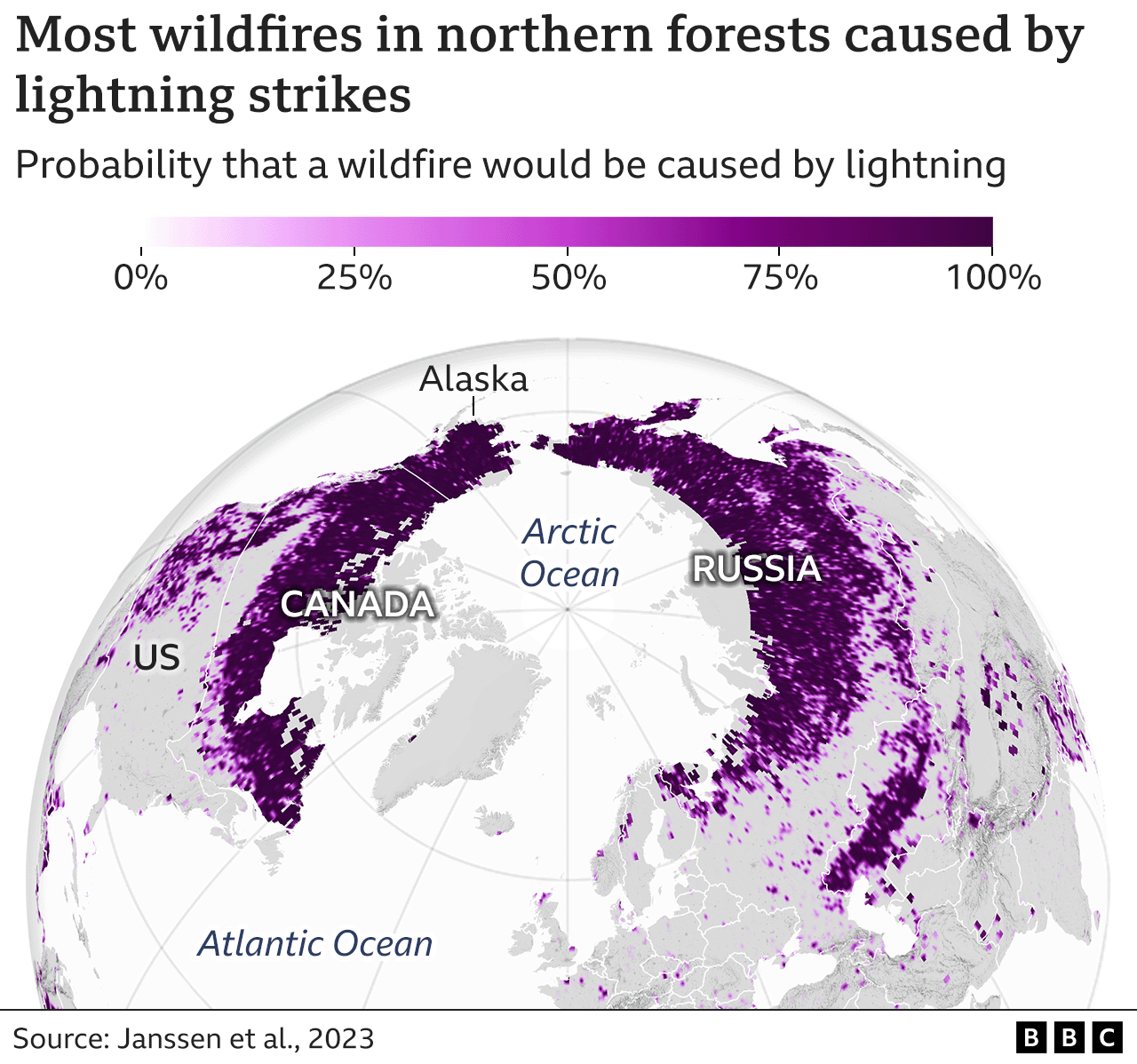

This new study used machine learning tools to develop a new global map showing forest fires by their ignition sources.

The authors found that 77% of burned areas in these forests are related to lightning ignitions. This is very different from tropical regions where humans are the main cause.

In the remote forests where lightning is the main fire starter, these conflagrations can rapidly turn into mega-fires.

“When a thunderstorm passes through this landscape, there are thousands of lightning strikes, and some hundreds of them start little fires,” said Prof Sander Veraverbeke from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, one of the authors on the research paper.

“And these can grow together into mega-fire complexes that become the size of small countries. Once these fires are so big, it becomes very difficult to do anything about them.”

Using climate models, the authors also found that lightning frequency over intact northern forests would increase by 11-31% for every degree of global warming.

This poses a threat of increased emissions as the trees contain large amounts of carbon, as do the soils in which they grow.

These “extratropical forests” are often in regions of permafrost and fire may also amplify the emissions of greenhouse gases as the icy ground melts, by up to 30% by the end of this century under moderate levels of warming.

“Our research highlights that extratropical forests are vulnerable to the combined effects of a warmer, drier climate and a heightened likelihood of ignitions by lightning strikes,” said Dr Matthew Jones from the University of East Anglia.

“Future increases in lightning ignitions threaten to destabilise vast carbon stores in extratropical forests, particularly as weather conditions become warmer, drier, and overall more fire-prone in these regions.”

While fires in tropical forests can be limited by education and intervention programmes to prevent people burning these areas, stemming fires from lightning is far more difficult.

The researchers believe the most effective step would be major cuts in emissions of warming gases which might in turn limit the rise in lighting strikes. The possibility of more fires as large as the ones seen in Canada this year should be a wake-up call, experts say.

“The fire season was unprecedented and hard for a lot of people to ignore,” said Dr Katrina Moser from the University of Western Ontario, who wasn’t involved in the study.

“But my take-home message is it’s not too late to make a change. Take forest fires as a warning but not as reason to do nothing.”